Beowulf and me

by Maria Dahvana HeadleyMy love affair with Beowulf began with Grendel’s mother, the moment I encountered her in an illustrated compendium of monsters, a slithery greenish entity standing naked in a swamp, knife in hand. I was about eight, and on the hunt for any sort of woman-warrior. Wonder Woman and She-Ra were fine, but Grendel’s mother was better. She had a ferocious look and seemed to give precisely zero fucks, not that I had that language to describe her at that point in my life. In the book I first saw her in, there was no Grendel, no Beowulf, no fifty years a queen. She was just a woman with a weapon, all by herself in the center of the page. I imagined she was the point of whatever story she came from. When I finally encountered the actual poem, years later, I was appalled to discover that Grendel’s mother was not only not the main event but also, to many people, an extension of Grendel rather than a character unto herself, despite the significant ink devoted to her fighting capabilities. It aggravated me enough that I eventually wrote a contemporary adaptation of Beowulf – The Mere Wife, a novel in which the Grendel’s mother character is a protagonist, a PTSD-stricken veteran of the United States’ wars in the Middle East. That might have been the end of it, but by that point I’d tumbled head over heels into Beowulf itself, and was, like everyone who ever translates it, obsessed.

It’s a somewhat unlikely object of obsession, this thousand-ish-year-old epic. Beowulf bears the distinction of appearing to be basic – one man, three battles, lots of gold – while actually being an intricate treatise on morality, masculinity, flexibility and failure. It’s 3,182 lines of alliterative wildness, a sequence of monsters and would-be heroes. In it, multiple old men try to plot out how to retire in a world that offers no retirement. Hoarders of all kinds attempt to maintain control of people, halls, piles of gold, and even the volume of the natural world. Queens negotiate for the survival of their sons, attempt to save their children by marrying themselves to warriors, and, in one case, battle for vengeance on their son’s murderers. Graying old men long for one last exam to render them heroes once and for all. The phrase “That was a good king” recurs throughout the poem, because the poem is fundamentally concerned with how to get and keep the title ‘Good’. The suspicion that at any moment a person might shift from hero into howling wretch, teeth bared, causes characters ranging from scops to ring-lords to drop cautionary anecdotes. Does fame keep you good? No. Does gold keep you good? No. Does your good wife keep you good? No. What keeps you good? Vigilance. That’s it. And even with vigilance, even with courage, you still might go forth to slay a dragon (or, if you’re Grendel, slay a Dane), die in the slaying, and leave everyone and everything you love vulnerable. The world of the poem – a fantastical version of Denmark in the fifth to early sixth century and the land of the Geats, in present-day Sweden – is distant, but the actions of the poem’s characters are familiar.

Beowulf bears the distinction of appearing to be basic – one man, three battles, lots of gold – while actually being an intricate treatise on morality, masculinity, flexibility and failure.”

As much as Beowulf is a poem about Then, it’s also (and always has been) a poem about Now, and how we got here. The poem is, after all, a poem about willfully blinkered privilege, about the shock and horror of experiencing discomfort when one feels entitled to luxury.

When I think about Beowulf these days, some thirty-five years after I first saw Grendel’s mother standing alone with her knife and her rage, I often find myself thinking about Beowulf’s barrow. Some think it’s just meant to be a monument. Others think the barrow is intended to be a beacon, meant to warn ships of jutting land. My interpretation varies depending on the day, but I tend to think that the stories themselves are the lighthouses.

Sometimes, I picture a map of the world, the kind of map I used to pore over as a child, obsessing over the now-familiar warning: HIC SUNT DRACONES. On that imaginary map, I’ve added story-lighthouses. They’re all over the place. Look here, their light tells us. Here’s a safe spot to tie up your boat and disembark. Here’s a spot to watch out for. Out here are dragons. Out here are the stories of those dragons, and of those heroes – and more.

There are also stories that haven’t yet been reckoned with, stories hidden within the stories we think we know. It takes new readers, writers and scholars to find them, people whose experiences, identities and intellects span the full spectrum of humanity, not just a slice of it. That is, in my opinion, the reason to keep analyzing texts like Beowulf. We might, if we analyzed our own long-standing stories, use them to translate ourselves into a society in which hero making doesn’t require monster killing, border closing, and hoard clinging, but instead requires a more challenging task: taking responsibility for one another.

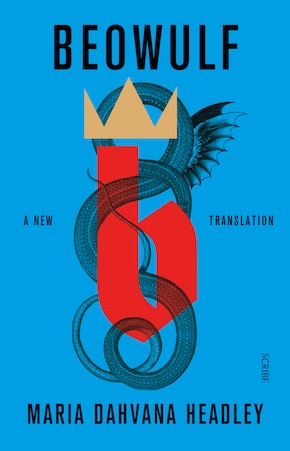

from the introduction to Beowulf: A New Translation (Scribe, £9.99)

Maria Dahvana Headley is a #1 New York Times bestselling author and editor, most recently of the novels The Mere Wife, Magonia, Queen of Kings, and the memoir The Year of Yes. With Kat Howard she is the co-author of The End of the Sentence, and with Neil Gaiman she is the co-editor of Unnatural Creatures. Her short stories have been shortlisted for the Shirley Jackson, Nebula and World Fantasy Awards, and her work has been supported by the MacDowell Colony and by Arte Studio Ginestrelle. She was raised with a wolf and a pack of sled dogs in the high desert of rural Idaho and now lives in Brooklyn. Beowulf: A New Translation is published in paperback and eBook by Scribe.

Read more

mariadahvanaheadley.com

@MARIADAHVANA

@ScribeUKbooks

Author portrait © Beowulf Sheehan