Beyond language

by Lee Seong-bok

Indeterminate Inflorescence is a collection of aphorisms on poetry-writing taken from the creative writing lectures of Lee Seong-bok, one of South Korea’s most prominent living poets. These 470 meditations, collected by his students, are evocative micro-poems in their own right. Some express ideas at once familiar and breathtakingly new – truths we could sense but not put into words; others unfurl fresh vistas and worlds to explore in their exciting and inspiring poetics.

Together, they offer an invigorating and original answer to the questions: How – and why – do we write at all? What does it mean to create? And how should we see the world?

—

0.

“Inflorescence” is the order in which flowers bloom on a stem. An alternative word for inflorescence in “pure Korean” is “flower-sequence” (kkotcharae). There are two kinds of inflorescence: “Determinate inflorescence” means flowers bloom from top to bottom (basipetal) with limited growth. “Indeterminate inflorescence” means the flowers bloom from bottom to top (acropetal), and growth is unlimited. We might say poems bloom in “indeterminate inflorescence” as they grow from concrete to abstract, from secular to sacred.

Poetry takes its form in its endless failure to express what language cannot.

1.

Poetry is what is unsayable. To blurt out what is unsayable is to ignore this fundamental premise.

2.

Poetry is an encounter with unexpected truth. What awaits us when we begin writing a poem is the unknown; only the unwritten can make us happy. Poetry is the promise of joy in the as-yet unknown.

3.

Language can be messy or vulgar, yet without it there is no seeing or hearing. Language is not a means to an end but an object and objective in itself. To use it as a mere tool only leads to unhappiness. Writing is language in the act of escaping and adventuring into the unknown.

4.

When writing poetry, the words must always be separated from the self. Otherwise, the words become oppressed by the brain.

5.

Unlike theorists, writers are completely dependent on the compulsion of language. It’s language that casts the net. Writers haul it in. Once you grasp this, you’ll never have to rely on theories again.

6.

That a wealth of experience is essential to write poetry is a myth rooted in the mistaken belief that poetry exists within the poet. Neither is poetry in objects. When Wang Shouren tried to achieve a wider understanding of things through the investigation into the essence of bamboo, his efforts only left him heartsick. Poetry ultimately resides in language; thus language, corrupted as it is by the real world, is sacred. Poets and objects may be nothing more than the hosts poems pass through before sprouting the wings of language.

7.

At one end of the poetic spectrum is beauty and abstraction; at the other, truth and concreteness. To focus on beauty dilutes truth, leaving only pure music, an expression of taste. This is audible poetry, which moves from the present to the future. To focus on truth exposes what’s hidden, and meaning sharpens into view. This is visible poetry, which moves from the present to the past. Poetry exists between these two extremes.

8.

In Seon Buddhism, “to see what’s fundamental” is understood as “to see is fundamental”. Perhaps poems can arise from switching subject and verb, what is seeing and what is seen.

9.

One and only one image can carry over many emotions; no emotion can carry over one and only one image.

10.

We do not give voice to our poems when we write them; our poems, rather, give voice to us. Words, in a sense, give voice to themselves through us. Perhaps that’s the meaning of the phrase veritas veritatum (truth begets truth).

11.

The self can never speak itself; the speaking self would be left behind. If that speaking self speaks the self again, that speaking self would be le behind. Poetry takes its form in its endless failure to speak what cannot be spoken.

12.

To write poetry is to dig a waterway for words. Poetry allows words to flow through you. The poet must not force the flow of words but rather watch and wait.

From Indeterminate inflorescence, translated by Anton Hur (Allen Lane, £12.99)

—

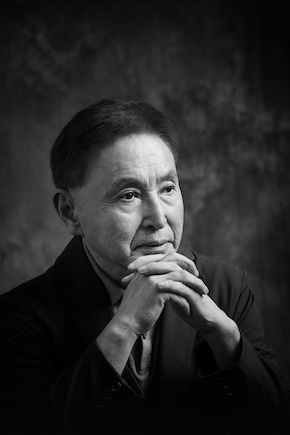

Lee Seong-bok, often referred to as a poet’s poet, was born in Sangju, Korea. He managed to enter the prestigious Gyeonggi High School in Seoul where he was inspired to write by his Korean teacher, the poet Kim Won-ho, as well as by the work of poet Kim Soo-young. After graduating from Seoul National University with a degree in French, he worked at Keimyung University in Daegu for forty years, interrupted by a stint of living in Paris, where he studied the poststructuralists as well as the tenets of Seon Buddhism. He has written eight collections of poetry and numerous other books including academic and mainstream literary criticism, creative writing, and two books of essays on photography. Indeterminate inflorescence is published by Allen Lane in hardback and eBook.

Read more

@AllenLaneBooks

@PenguinUKBooks

Author photo © Lee Seong-bok

Anton Hur was born in Stockholm, Sweden and currently lives in Seoul. He won a PEN Translates award for Kang Kyeong-ae’s The Underground Village, and his translation of Bora Chung’s Cursed Bunny was shortlisted for the International Booker Prize. His other translations include The Prisoner by Hwang Sok-yong (Verso, 2022), I Want to Die but I Want to Eat Tteokbokki by Baek Sehee (Bloomsbury, 2022), Grocery List by Bora Chung (Hanuman, 2024), and That Summer’s End by Lee Seong-bok (Knopf, 2026). He is the author of No One Told Me Not To (Across Books, 2023) about the struggles of a translator, and the novel Toward Eternity (HarperVia, 2024).

antonhur.com

@antonhur