The big W

by S.E. CraythorneCreative writing courses have taken something of a beating in the press of late. Their proliferation is probably one of the main reasons for this, but it is also symptom of their success. I’m not ashamed to say that I became a writer through creative writing groups. They have offered support and inspiration. They have taught me my craft. And I have experienced them in a number of guises.

The first I attended, when still an undergraduate student in Manchester, was run by the local council. It comprised one man who would write only in crayons, another who spoke constantly to his dead mother, and two women obsessed with car boot sales. My friend Ali and I sat hunkered in a corner, and wondered what we had wandered into. But the leader of the group was sympathetic and inspiring. He knew – as I was quickly learning – that people attend creative writing groups for different reasons, just as people write for different reasons.

Ali and I were hungry for publication and hoping to improve our craft; it seemed that the rest of the group were there to socialise and enjoy themselves. We soon realised that one ambition did not necessarily cancel out the other. It’s a hard lesson for an earnest teenager that your craft does not have to be painful, especially when you have company. The main achievement of our attendance was that we actually started to do what we’d been telling everyone we wanted to do: namely, write. We practiced. I have a great affection for that first class – eccentric as it was. Most of what we wrote was awful, but this was a safe environment. Through the kindly criticism of the rest of the group, I was surprised to find myself getting better.

At the end of the course, the leader took me to one side and told me he thought I might have talent.

Unfortunately, without the support of the group, life and my studies took over. Ali and I tried another couple of groups, but now that I’d been told I might have ‘talent’, I think I was scared to mess it up. If I didn’t write, then no one could disprove that man’s kind words.

My workshop group was made up of talented writers and astute critics. They stood for no nonsense. The workshops themselves were gruelling, but prepared you like nothing else for the rigour of a professional edit.”

By my mid-twenties I was feeling – as many do at that age – a bit lost. I still had the hankering to write, but I only had a handful of short stories to my name. I decided, finally, to put my abilities to the test and applied to the MA Creative Writing at UEA. I had a disastrous interview: one of the interviewers choked on their water and had to leave the room; I spoke endlessly about the book I was reading (I was so dismayed by it, I threw the book in a bin on my way home); at one point I refused to give details of the novel I hoped to write, until I was gently reminded that this is what I’d have to talk about on the course. It was terrible but, to my great surprise, they accepted me. In fact I was so surprised, I almost refused the offer – what good could the course be if they accepted people like me?

I’m so glad I accepted. What followed was the most creative and concentrated year of learning of my life. My workshop group was made up of talented writers and astute critics. They stood for no nonsense. The workshops themselves were gruelling, but prepared you like nothing else for the rigour of a professional edit. They taught me when to murder my darlings, and when to stand my ground. Something not often mentioned is the amount you learn from criticising someone else’s work. The same themes emerge, and you begin to see the weaknesses in your own practice.

Creative writing courses certainly hold no secret formula for success. Rose Tremain said it best when describing the MA at UEA as seven years’ work in one year. It’s a time of doing what you most love doing with no interruptions. It’s a treat, but it’s also hard work. If you’re lucky, you may get to call yourself a Writer with a capital W – even if it’s only to yourself and only in your head and only for one year.

After I graduated, life – as is its wont – took over again. I now knew what I wanted to do, but the pressures of rent and the desire to feed myself meant that I had to work. I took three low-paid jobs, not wanting a career to get in the way of my writing. And ignored the fact that having three jobs meant that I had no time to write. Occasionally, I took out the work I’d produced on my MA, but, as time passed, I realised that novel had just been practice. It wasn’t what I wanted to write, but I didn’t have the time to think about what it was I did want to write.

Then I got ill. I suffered a long period of severe depression. I was unable to work or to write for a long time.

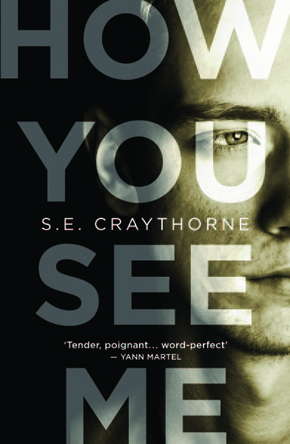

I was still ill when my mother suggested a local creative writing group run by Tom Corbett, the poet and then CEO of Gatehouse Press. It was this group that picked me up and got me thinking and working again. We did writing exercises and played with form and structure. It was in this group that I started what would become my debut novel, How You See Me. Thanks to their support and criticism it became more than writing as therapy, it became a real book.

It took me a long time to be happy again, and longer to become a published writer. But the latter was achieved through a history with creative writing groups and courses. They are safe places for that most dangerous of practices – creativity. Without them I would never have become a writer. Maybe one day I’ll earn the capital W.

S.E. (Sally) Craythorne was bought up on a smallholding in rural Norfolk and has worked as a bookseller, journalist, artist’s model, English teacher and librarian. She lives in Norwich with her husband and twin daughters. She is a graduate of the Creative Writing MA at the University of East Anglia. An extract from How You See Me was longlisted for Mslexia‘s Women’s Novel Competition, and the novel is now published by Myriad Editions. Read more.

S.E. (Sally) Craythorne was bought up on a smallholding in rural Norfolk and has worked as a bookseller, journalist, artist’s model, English teacher and librarian. She lives in Norwich with her husband and twin daughters. She is a graduate of the Creative Writing MA at the University of East Anglia. An extract from How You See Me was longlisted for Mslexia‘s Women’s Novel Competition, and the novel is now published by Myriad Editions. Read more.

secraythorne.moonfruit.com

@secraythorne

Author portrait © Jemma Mickleburgh