Black Country noir

by Kerry Hadley-Pryce

WHEN I SIT DOWN TO WRITE, I always – and I mean always – wonder why it is that I sort of default to ‘the dark side’, and why said dark side always positions itself in my writing here, where I live – where I actually live – in the Black Country. You probably don’t even know where it is, this Black Country of mine. Be still, because nobody really does. Not even me. Geographically, okay, I know where it is, of course. I mean, I always find my way home, no problem: it’s not far from Birmingham. It’s part of the West Midlands. But forget about geography for a moment, because that’s only one of the component parts of the Black Country. The Black Country is about linguistics (there are numerous dialects), food, culture and attitude. The landscape and geology play a part in it all. In common vague and irritating parlance, it’s complicated… I wrote a PhD on this, that’s how complicated it is. But more and more, its creative output is becoming part of its definition, and when I was asked to make a list of my favourite Black Country noir novels, I had to think quite hard about what I might inflict on the uninitiated.

‘Black Country noir’ is, I think, a new genre of novels and short stories that have a kind of ‘sensation of place’. It’s a meld of crime, thriller, weird and gothic fiction. There are elements of horror, always a sense of foreboding. I think this is a genre that has been brewing for decades, and the tradition of Black Country novels has been kind of nurturing it.

In no particular order, the tradition of Black Country noir? Here goes:

Many of Francis Brett Young’s novels are set in his imaginary Black Country, and The Iron Age (1916) sums up the grime and power of industrialisation and the effects on the Willis family. Anthony Cartwright’s five brilliant novels – all set in his home town of Dudley (the so-called ‘capital’ of the Black Country) simmer with Black Countryness: The Afterglow (2004) deals with the fractured nature of a community, and the effect of tragedy on a family. Heartland (2009) mixes football culture with political unease, and the rise of the British National Party in the region; How I Killed Margaret Thatcher (2012) is an intensely dark story that melds the political history of the Thatcher period and its fictive effects on the death of industry in the Black Country; Iron Towns (2016) tells the tale of Liam, Dee Dee, Goldie and Mark, once again using the theme of football and demonstrating the decline of the region through reference to mythology to add a sense of folk horror to the genre; The Cut (2017) is a ‘Brexit novel’ in which the Black Country is used as a perfect setting for the ‘forgotten people’ and is an exploration of the effects of diminishing industrialised communities.

The Black Country is about linguistics (there are numerous dialects), food, culture and attitude. The landscape and geology play a part in it all. In common vague and irritating parlance, it’s complicated…”

Raphael Selbourne’s Beauty (2009), set in Wolverhampton, is an impressive story of a young Bangladeshi woman who comes to the region. As an outsider, her views and understanding of the place, the characters she meets and the isolation she feels evoke a feeling of claustrophobia emblematic of Black Country noir. Similarly, R.M. Francis’ two short novels, Bella (2020) and The Wrenna (2021) are beautifully unsettling. Francis is a poet, first and foremost, and his brevity of prose presents us with a sense of realism and working-classness tied up with myth and folk story.

More recently, Daniel Wiles’ Mercia’s Take (2023) is a remarkable historical novel of the Black Country’s heritage as a mining area, with all the darkness and danger that came along with it. There is an intensity to the prose that conjures that unsettling sensation that rings so true with Black Country noir.

I know I said ‘in no particular order’, but this final novel is the novel that was my personal spark of inspiration for my writing. It’s Joel Lane’s From Blue to Black (2000). A band called ‘Triangle’ try to make it big in the music scene; there’s unrequited love, sex and drinking and broken lives. It’s a story that, in terms of place, straddles Birmingham and Stourbridge in the Black Country. The Black Country canal network is a significant character, and the prose style is hypnotic, dark – frightening, even. I had read this novel in the early 2000s. I loved it. I live in Stourbridge, and I’d walked the route along the towpath that characters David and Karl had taken. I couldn’t shake the story off. To me, this is the first real Black Country noir novel. It really does have everything. When I wrote my first novel, The Black Country, my editor Nicholas Royle said he would send it to Joel Lane for a quote. My God, I nearly died of joy. But it wasn’t to be. Joel Lane died suddenly in 2013. It’s an incredibly sad loss, but Influx Press have committed to republishing his novels: From Blue to Black (for which I’m pleased to say, I wrote the introduction); The Blue Mask; The Witnesses are Gone, and his hitherto unfinished final novel, Midnight Blue.

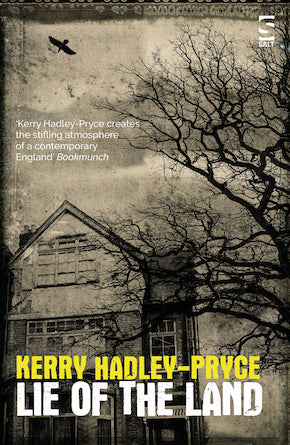

I like to think that my own Black Country noir novels are following the tradition set by this posse of brilliant writers – and are developing the genre even further. It’s an evolving thing, a bit like the place itself. And of course, we have to talk about me, don’t we? Just a bit. And my latest novel, Lie of the Land. It’s all that Black Country noir should be, I think: dark, sinister, definitely unsettling. There are elements of crime and thriller, and the gothic, and folk horror. I wonder what Joel Lane would have thought of it. I hope he’d have approved. And the more I think about that, the more it becomes clear why I default to ‘the dark side’. There’s no choice really, not for me, anyway.

—

Kerry Hadley-Pryce lives and writes in the Black Country. She has a PhD in creative writing and teaches creative and professional writing at the University of Wolverhampton. She co-edited Writing Under Fire: Poetry and Prose from Ukraine & the Black Country, and has short stories published in Best British Short Stories 2023, Takahe Magazine, Fictive Dream and The Incubator. Her novels The Black Country (2015), Gamble (2018), God’s Country (2023) and Lie of the Land (January 2025) are published by Salt Publishing.

Read more

kerryhadley2001.wixsite.com

@Kerry2001

@kerryhp.bsky.social

Instagram: kerry2001

@saltpublishing.com

Instagram: saltpublishing