Boualem Sansal: Resistance writer

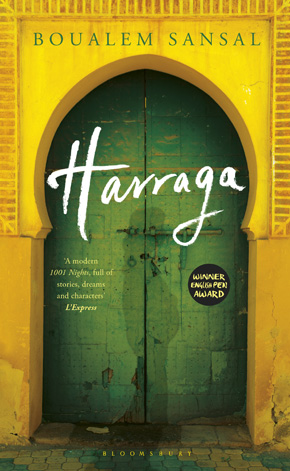

by Mark ReynoldsBoualem Sansal began writing his first novel, Le serment des barbares, in his late 40s while still working as a civil servant. When the book was published in 1999, containing criticism of the political situation in Algeria, he was asked to go on leave. In 2003, after further criticism of President Abd al-Aziz Bouteflika’s regime, he was dismissed from government, and in 2006 his books were banned altogether following the publication of an open letter to the Algerian government. As he is to London to promote his latest novel Harraga, I fire off some questions via his translator Frank Wynne.

MR: What was the first spark that led you to become a fiction writer?

BS: It was triggered the civil war that decimated my country during the 1990s. It forced everyone in Algeria to choose sides and to act. My politics are democratic and secular, so sided with those who insisted “No to a Police State, no to an Islamic state.” They battled on both fronts, against the forces of the dictatorship and against the fundamentalists. My first novel is an account of that war, and an attempt to explain the various factions and the outcome. The fact that a number of Algerian intellectuals, many of whom were close friends, were assassinated by Islamists was a powerful motivating force.

Did you believe when you began writing that life as a government employee and a novelist could be compatible? And at what point did you realise you were heading for controversy and censorship?

Civil servants in Algeria, like those all over the world, are bound by official secrecy. But the government of Algeria is not legitimate, it is a dictatorship, one that I decided to oppose through my writings and any other means at my disposal. In my heart, I decided that I owed no loyalty to this government. From the outset, before the novel was even published, I knew that it would provoke fierce arguments and polemics and that I would be attacked by the government and by the Islamists. This was something I was prepared to accept. We were at war and war necessarily requires an intellectual as well as a physical battle.

You have been described as a writer who is ‘exiled in his own country’. Is this a phrase you identify with? And how much more uncomfortable would your situation have to become to make you want to leave Algeria?

In dismissing me from my job and attempting to discredit me with the public, the government did everything in its power to isolate me, cutting me off completely from Algerian society. No longer invited anywhere, and smeared by the government as a traitor to the national cause, I have become like a castaway on a desert island. Nonetheless, I am determined to stay in Algeria; I refuse to allow the government or anyone else to drive me out of my country, cut me off from my family and my friends. My circumstances are difficult and sometimes dangerous, but that is no reason to change a fundamental decision. A resistant must resist, not surrender.

In Algeria, Camus is the subject of a never-ending national debate… People still argue that he was a colonialist, but these days they recognise that he was devastated by the war, and was reconciled to independence.”

What have been the main failings of the Bouteflika regime?

Bouteflika has always been a dictator. He and Boumediene mounted a coup d’état immediately after the country gained independence on 5 July 1962, in order to install the puppet president Ahmed Ben Bella. They overthrew Ben Bella in 1965 and directly seized power – which they clung to with violence and murder until the death of Boumediene in December 1979. Bouteflika found himself sidelined by the new dictator Chadli Bendjedid, but in 1999 he was returned to power following a coup d’état organised by a number of generals who, during the civil war, had been guilty of torture, of war crimes, even genocide, and who needed a strategist like Bouteflika to save them from the International War Crimes Tribunal. Since coming to power, Bouteflika has used the most abhorrent tactics as a leader: intimidation, nepotism, exclusion and corruption (nowadays Algeria is classed among the 10 most corrupt countries in the world). All this contributed to destroying the economy of the country, which now survives entirely from the sale of crude oil.

Explain the term ‘harraga’, and why you chose it for the title.

The word was invented by the young men who took the plunge, choosing clandestine emigration as a means to escape war, unemployment and their meaningless lives. The word means ‘those who burn’, in the sense of burning all ties with their country, their family, their friends, and eventually putting a match to their own lives since they know there is little chance that they will survive the crossing, still less that they will find what they seek in Europe should they get there, and yet still they leave.

Harraga is about the struggle of women in a patriarchal society, the stifling effects of fundamentalism, and also the power that comes from unity and friendship. Why did you want to focus on women’s lives for this book?

I have always been a militant feminist. I believe it is vital to the existence of a country, to balance, to democracy, that women should have the same rights as men. It is crucial that they be free of all those constraints that seek to turn them into second-class citizens: religion, tradition, and the sort of quasi-apartheid laws that incarcerate them in a sort of prison without hope. It is a subject I deal with in all my novels. In Harraga it is the central theme.

Your character Yazid in Rue Darwin reflects that “perhaps Islam and the Muslims are simply not compatible”, and you have said elsewhere that “Islamism is a fascism”. How can fundamentalism be supplanted, in Islam and elsewhere?

We have to be clear-sighted, human nature is not only or entirely turned toward what is good. Extremists have always existed and will always exist. Considering the way in which we are destroying our planet, and how many wars we fight every century, one might reasonably wonder whether the instinct for goodness is in our genes. The goal, therefore, cannot be to eliminate extremes – something we could never achieve – but to create a political system and a social structure that makes it possible to replace them, to limit the damage they can do. It would appear that only democracy can do this. As for secularism, it is yet to be proven that it is effective against religious extremism.

It would take too long to flesh out all the evidence, but the similarity between Islamic fundamentalism and Nazism is obvious, both in its ends and in the means used to achieve those ends (authoritarianism, eradicating non-believers, the cult of heroes and martyrs, the worship of power and violence, the indoctrination of children into paramilitary organisations). But it also stems from the deep ties during the 30s and 40s between the World Islamic Congress led by the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem and Hitler’s National Socialist Party.

Name five books or writers from Algeria that should be essential reading within and outside the country.

Here are a few books for those who want to have a sense of Algerian literature (all of them initially published in France because of the strict censorship in Algeria):

Nedjma by Kateb Yacine

The Repudiation by Rachid Boudjedra

Nowhere in My Father’s House by Assia Djebar

What the Day Owes the Night by Yasmina Khadra

Odysseus’ Dog by Salim Bachi

Which world books and writers do you regard as the most important, and why?

Journey to the End of the Night by Louis-Ferdinand Céline

Love in the Time of Cholera by Gabriel García Márquez

Absalom, Absalom by William Faulkner

East of Eden by John Steinbeck

The Trial by Franz Kafka

1984 by George Orwell

All of these books offer a keen analysis of a particular period or create an original and powerful new style of writing.

Which English- and French-language writers are most popular today in Algeria?

French writers: Camus, Patrick Modiano, Le Clézio…

English: Agatha Christie, Virginia Woolf…

Was Camus right to oppose Algerian independence? Should he have stated his case more vehemently? Or were both sides in the Algerian War simply too entrenched to reach any kind of compromise?

In Algeria, Camus is the subject of a never-ending national debate. Before the Civil War (which began in 2000), Camus was condemned by the majority of Algerian intellectuals. He was criticised for being opposed to independence and for condemning the terrorist tactics of the FLN, which most Algerians considered a legitimate weapon of the weak against the powerful. When he was arrested by the French during the Battle of Algiers and accused by journalists of resorting to terrorist tactics, the rebel leader Ben M’hidi declared: “Of course, if we had your fighter planes, it would be a lot easier for us. Give us your bombers, and you can have our handbags and baskets.” (The explosives used by Algerian activists carrying out public bombings were often concealed in handbags and baskets).

Now that Algeria has suffered through civil war and Islamist terrorism, Algerian intellectuals are changing their minds about Camus. He is much read these days. They now recognise that the tactics of the FLN constituted terrorist acts, but they also insist – more loudly than ever – that France acknowledge the war crimes it committed in Algeria.

People still argue that Camus was a colonialist, but these days they recognise that he was devastated by the war, by the horrific scale of the violence, and was reconciled to independence believing that it was the only thing that could stop the murderous cycle of violence.

In what ways did the Civil War mirror the war for independence?

Two single-minded adversaries, both determined to use all means at their disposal to triumph, a rejection of dialogue and to negotiate, radicalism and terrorism – all of these things are common to both wars. These days, Algerians who lived through both wars recognise the terrible parallels between the two.

What will have to happen for your work to be published again in Algeria?

My books have little chance of being published in Algeria anytime soon. Algerian publishers have no wish to publish them, they believe there is no readership for my novels. In part, they feel it is a matter of language: French speakers who want to read my books buy them in France. Most Arabic speakers have no desire to read my books, and those who do would want them translated into Arabic, something that is unlikely to happen since the market for literature in Arabic is even smaller.

Which of your novels will be the next to appear in English?

For the moment, two of my books have been translated and published by Bloomsbury: An Unfinished Business (Le Village de l’Allemand) and Harraga. I think that Rue Darwin and/or Governing in the Name of Allah might one day be published in English; I certainly hope so.

What are you working on next?

I am currently working on a play and a new novel. The play is about impertinence, while the novel imagines what the world will be like if the spiralling level of violence perpetrated by mankind against man and against nature continues to rise inexorably.

Boualem Sansal was born in Algiers in 1949 and today lives outside the city. He trained as an engineer and economist and has worked as a teacher, consultant, entrepreneur and a senior official in Algeria’s Ministry of Industry. His novels have won many top literary prizes in France, where they are published by Gallimard. Harraga is out now from Bloomsbury in hardback and eBook and his earlier novel An Unfinished Business is available in paperback and eBook. Read more.

Boualem Sansal was born in Algiers in 1949 and today lives outside the city. He trained as an engineer and economist and has worked as a teacher, consultant, entrepreneur and a senior official in Algeria’s Ministry of Industry. His novels have won many top literary prizes in France, where they are published by Gallimard. Harraga is out now from Bloomsbury in hardback and eBook and his earlier novel An Unfinished Business is available in paperback and eBook. Read more.

Author portrait © Helle Gallimard

Frank Wynne is a literary translator from French and Spanish. His work has earned him major prizes including the 2002 IMPAC Prize for Atomised by Michel Houellebecq and the 2005 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize for Windows on the World by Frédéric Beigbeder. He is the translator of Boualem Sansal’s An Unfinished Business and Harraga.

terribleman.com