Writing on with a joyful cackle

by Brett MariePerhaps Stephen King skimmed over the fine print when he signed his deal with the Devil to become one of the most successful authors of all time. Maybe the streetlights were too dim on that gloomy night at the crossroads, and he missed the clause that stated: “Henceforth, upon expiration of x months on worldwide bestseller lists, any book written by The Author shall be relegated to the Horror section of every bookstore.” Likewise this one: “No serious Award or Accolade shall be conferred on The Author or his work without a suitably pissy outcry from the Literary Establishment.” It’s a shame King didn’t have a lawyer with him, a Daniel Webster type, to point out these unfavourable terms and get them altered.

He feels the repercussions to this day. “I don’t think of myself as a genre writer,” he told the Los Angeles Review of Books last month. But although he’s never objected to labels such as ‘horror’ or ‘science fiction’ writer, he admits: “Whenever I read it in print, I kind of go ‘raaawr.’ It’s a fight you can’t win. The same way that you don’t really want to get into this tar baby of serious literature versus popular fiction, or American literature versus genre, that sort of thing.”

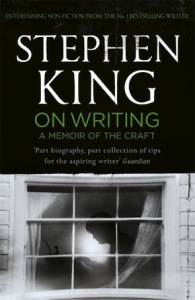

As much as questions of legitimacy might dog him, though, I’m guessing that King doesn’t regret signing the deal as it was written. Critics be damned; above all else, more than any author out there, King is in love with the craft, the process, the very concept of storytelling. His 2000 memoir On Writing did a fine job articulating that love. Early in that book, he described his epiphany as a young boy when his mother encouraged him to stop copying word-for-word the texts of his Combat Casey comic books, and to start writing his own stories: “I remember an immense feeling of possibility at the idea, as if I had been ushered into a vast building filled with closed doors and had been given leave to open any I liked.”

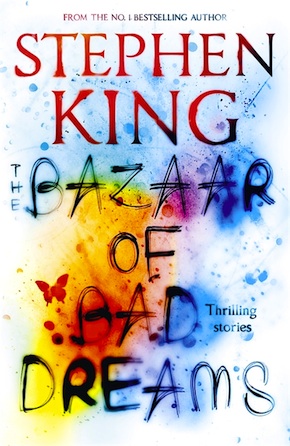

King hasn’t gotten tired of opening new doors, as evidenced by the seven novels he’s put out in just the past five years. But just in case you thought the infectious enthusiasm conveyed in On Writing may have worn off, and you’re wondering if the guy might start losing steam in his old age, he’s back today with The Bazaar of Bad Dreams as a booster shot. Each short story in this new collection is prefaced with an author’s note describing that story’s origins. These notes serve to put us inside the author’s head, to explain his motivations for writing about a particular event or setting. Individually, they are interesting enough, and shed new light on pieces his more devoted fans might have read before (most of the stories have been previously published in magazines or as eBooks). Lined up together, however, they accomplish something far greater. Like On Writing, this peek behind the curtain brings that zest for narrative, that feeling of possibility, back into focus. “Only through fiction can we think about the unthinkable,” he declares while introducing ‘Herman Wouk is Still Alive’, a story he conceived from a real-life news item about a horrific car crash. Before giving us ‘Premium Harmony, he admits: “I wrote [the story] shortly after reading more than two dozen [Raymond] Carver stories, and it should come as no surprise that it has the feel of a Carver story.” In each instance, we get the fleeting image of King in his study, leaning back from his desk and sharing a secret or a pearl of wisdom with us over his shoulder.

On the page he’s as nimble as ever, wriggling his way out of the horror straitjacket when it starts to chafe, then strapping himself back in once he’s ready for more blood and guts.”

Intimacies aside, it’s a gas to watch King bounce from one story to the next, leaping across genres from horror, to fantasy, to Western, seeking out stories wherever he can find them. The man might be a bit stiff in body following the car accident that nearly killed him years ago, but on the page he’s as nimble as ever, wriggling his way out of the horror straitjacket when it starts to chafe, then strapping himself back in once he’s ready for more blood and guts. Perhaps the uninitiated might miss the graphic gore, the “brains in their teeth” (King’s words) that are so associated with the author and yet so absent from broad swathes of this collection. But I doubt that will stop many readers from reading every story. King has argued repeatedly in the past that “what they come back for is the voice,” and the New England twang with which he serves up every sentence is just as strong in his genre-busting experiments (his narrative poems ‘The Bone Church’ and ‘Tommy’ come to mind) as it is in his balls-to-the-wall horror pieces.

I’ll grant that the horror stories in this collection are perhaps the most shopworn. ‘Mile 81’ runs the story of a carnivorous station wagon through a series of ‘Don’t-Go-In-The-Barn’ hoops that will induce déjà vu in even the most casual fan of the horror genre. And though King crows a bit in his introduction to ‘The Dune’ about the story’s final twist, I’m guessing that most readers will see it coming, as I did, from at least a few paragraphs away. But if you think that makes a lick of difference, then you’re missing the point. King’s sheer delight at finding himself once again in his favourite narrative landscape infuses even the most hackneyed passages with an infectious sense of excitement – something of a storyteller’s fever. Here, King becomes the Scoutmaster by the campfire, or the big kid in the tent at night with the flashlight under his chin, retelling his best ghost stories, then turning a toothy grin on the younger kids in the troop and cackling, “Skeered ya, didn’t I?”

I’ll grant that the horror stories in this collection are perhaps the most shopworn. ‘Mile 81’ runs the story of a carnivorous station wagon through a series of ‘Don’t-Go-In-The-Barn’ hoops that will induce déjà vu in even the most casual fan of the horror genre. And though King crows a bit in his introduction to ‘The Dune’ about the story’s final twist, I’m guessing that most readers will see it coming, as I did, from at least a few paragraphs away. But if you think that makes a lick of difference, then you’re missing the point. King’s sheer delight at finding himself once again in his favourite narrative landscape infuses even the most hackneyed passages with an infectious sense of excitement – something of a storyteller’s fever. Here, King becomes the Scoutmaster by the campfire, or the big kid in the tent at night with the flashlight under his chin, retelling his best ghost stories, then turning a toothy grin on the younger kids in the troop and cackling, “Skeered ya, didn’t I?”

But, the saying goes, is it Art? Does a Stephen King book have something to say, something worthwhile to add to our culture? That depends on whom you ask. There came a point a while back when it looked like King might have outlived the terms of his otherworldly contract. By 2003 it had been several years since Kathy Bates won an Oscar for playing one of his characters, and The Shawshank Redemption (based on a King novella) had worked its way into the public consciousness as a Great Film. The critical reception to On Writing hadn’t hurt, either; Roger Ebert, for one, claimed that it had “more useful and observant things to say about the craft than any book since Strunk and White’s The Elements of Style.” We could be forgiven for thinking, when the good people at the National Book Awards chose to present him with a medal for “Distinguished Contribution to American Letters”, that perhaps King had finally pole-vaulted himself onto the podium of the Literary Canon. In reality, he was hanging off the edge, and a swarm of naysayers, led by critic Harold Bloom, charged over to stomp on his fingertips. Calling King a writer of “penny dreadfuls”, Bloom decried the decision to give him an award that had previously gone to Philip Roth – as though the presenters had ripped the medal off of Roth’s neck to give it to King. (Bloom also neglected to mention another surprising previous recipient: Oprah Winfrey.) It fell to fellow genre writer Orson Scott Card to defend King’s artistic merit, writing that “King will be remembered when all the writers favored by his disparagers are forgotten. It is King who will teach our grandchildren what America was in our time.”

Ask me if a Stephen King book is Art, and I’ll make like I don’t hear you. I’m having way too much fun reading to stop and ponder such trivialities. This latest book might induce the occasional bout of queasiness, but above all, page after page of The Bazaar of Bad Dreams delivers an undiluted sense of joy. It’s the joy of a man doing exactly what he wants to do, a man who’s thrilled to be able to let us in on his fun. “Mostly what I do,” King told an audience in Washington last year, “I’m having a good time. I’m enjoying it, and if that gets passed on to you, that’s a good thing.” Does that count as a Distinguished Contribution to his field? King didn’t venture a guess, but he did offer his idea of the kind of contribution he’d like to make: “When somebody comes up and says to me, ‘You got me through a tough time,’ what else can you ask for?” There is no more noble goal in art than to make people happy, and no grander statement of purpose than “Gather round, I’ve got a story to tell.” The Bazaar of Bad Dreams has twenty stories to tell. Each one hits its mark.

Brett Marie, also known as Mat Treiber, grew up in Montreal with an American father and a British mother and currently lives in Herefordshire. His short stories such as ‘Sex Education’, ‘Housewarming’, ‘The Squeegee Man’ and ‘Black Dress’ and other works have appeared in publications including The New Plains Review, The Impressment Gang and Bookanista, where he is a contributing editor. He recently completed his first novel The Upsetter Blog.

Brett Marie, also known as Mat Treiber, grew up in Montreal with an American father and a British mother and currently lives in Herefordshire. His short stories such as ‘Sex Education’, ‘Housewarming’, ‘The Squeegee Man’ and ‘Black Dress’ and other works have appeared in publications including The New Plains Review, The Impressment Gang and Bookanista, where he is a contributing editor. He recently completed his first novel The Upsetter Blog.

Facebook: Brett Marie

@brettmarie1979

Stephen King is the bestselling author of more than fifty books. Many of his novels and short stories have been made into films, including Carrie, The Shining, Misery, Stand By Me, The Shawshank Redemption and The Green Mile. Over the years, King has had various cameo roles in film adaptations as well as playing rhythm guitar in the Rock Bottom Remainders, a rock-and-roll band made up of some of America’s bestselling and best-loved writers. He was the recipient of the 2003 National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters and lives with his wife, novelist Tabitha King, in Maine, USA. The Bazaar of Bad Dreams is published by Hodder & Stoughton in hardback, eBook and downloadable audio.

Stephen King is the bestselling author of more than fifty books. Many of his novels and short stories have been made into films, including Carrie, The Shining, Misery, Stand By Me, The Shawshank Redemption and The Green Mile. Over the years, King has had various cameo roles in film adaptations as well as playing rhythm guitar in the Rock Bottom Remainders, a rock-and-roll band made up of some of America’s bestselling and best-loved writers. He was the recipient of the 2003 National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters and lives with his wife, novelist Tabitha King, in Maine, USA. The Bazaar of Bad Dreams is published by Hodder & Stoughton in hardback, eBook and downloadable audio.

Read more.

stephenking.com

stephenkingbooks.co.uk

@StephenKing

Author portrait © Shane Leonard