Caryl Lewis: Storms and wonders and cultures on the edge

by Mark Reynolds

“Original and timely… show[s] the resilience of the human spirit, the tenacity and love that helps us survive.” Irish Times

One day, Nefyn discovers a man’s body on the shore, and manages to revive him. He is Hamza, a Syrian refugee who has been held captive at a nearby Army barracks, and was badly injured when a truck moving him from the base fell into the sea as the coast road was torn away in a landslide. As he recuperates at the cottage, they open up about their pasts, and we learn that Hamza’s wife was killed by a stray bullet and his son is missing. As she weans herself off the drugs Joseph left her, using them to ease Hamza’s pain, they exchange generations-old stories about mermaids and sea monsters and the call of the ocean, and begin imagining a future life together. And bit by bit, it becomes apparent that Nefyn inherited supernatural powers from her mother, who ‘belonged to the sea’ and disappeared when Nefyn and Joseph were very young. It’s a side of his sister that Joseph has been desperate to rein in…

The holiday homes are a comment on how difficult it is to sustain a living culture when you have homes that are empty half the year, and the cultural erasure that comes with changing the names of places and properties.”

Mark: There’s such a strong sense of place in Drift, with the stone cottage overlooking the cove, the empty holiday homes along the coast, and just being out in nature. Is this based on a specific village or stretch of coast?

Caryl: My mother was a singer, so when I was younger I spent a lot of time with my grandmothers who lived near Llangrannog, which is a beautiful, beautiful stretch of coastline in West Wales, and along the coast from Llangrannog at Aberporth is an Army base which tests munitions for use in conflict abroad. So I loosely based it around Llangrannog, and the holiday homes are a comment on how difficult it is to sustain a living culture when you have homes that are empty half the year, and the cultural erasure that comes with changing the names of places and properties. So yes, it was based on somewhere I know very well, that has lots of stories and language and folklore attached to it.

The detention centre and army barracks calls to mind Penally in Pembrokeshire, which was closed in 2021 after allegations of abuse and sub-standard living conditions. Did Hamza’s story spring from there at all?

Hamza’s story actually sprang from me visiting a very high-percentage Welsh-speaking town, and hearing a man speaking Welsh with a really distinctive accent. Asking around, and I found out he was from Syria, from Aleppo. He brought his family to Wales as refugees, and they had all learnt Welsh, the children all went to the local Welsh-speaking school, and I was just really struck by the fact that he had no preconceptions about the value of learning a minority language. He didn’t question it, he just said, “Well this is where we live, this is where I am now, and this is the language that will connect me to the people and to the landscape,” and he just learnt the language and speaks it fluently. There are so many Syrian refugees that have moved to West Wales, and there seems to be an ease of assimilation between the two cultures.

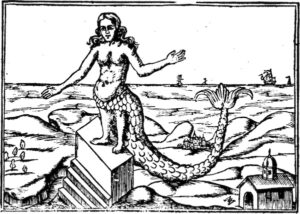

Myths of the sea are common to coastal communities all over the world. Hamza talks of the goddess Atargatis. What would the Welsh equivalent be?

There are many disparate stories of mermaids in Welsh, including the one from near Llangrannog which I drew on. She hasn’t got a name, actually, she’s just called a môr-forwyn. And there’s a lot about intermarriage with the people on the land, and about earning your freedom somehow. So you’ll often find a mermaid hiding a particular object, a cloak or something, and once that’s returned to them they’re allowed back to their element. They can either earn it back, or more interestingly take it back – I think that’s a better way of going about it. But there are so many stories along the Welsh coast, there’s the Tylwyth Teg as well, which would be the equivalent of fairies. Tylwyth Teg means ‘the fair people’, and they’re actually incredibly dark and brutal, they’re not nice fairies at all, and the mermaids here tend to have quite a dark edge to them as well, which personally I find more engaging, somehow, than the pretty girls on rocks.

We’re in lambing season at the moment, and you will see crows circling lambs and taking their eyes and tongues, and that is as much a part of nature as the spring flowers and all the beauty that happens at this time of year.”

A single by-the-wind sailor colony (Velella velella) washed up by the tide in California. Alex Wang/Wikimedia Commons

The natural world is beautifully observed, from the ever-changing sea to by-the-wind sailors drifting in on the tide and, on Joseph’s walks in the north, how each spot along the coast is “subtly distinct, in moth and bird and dialect.” Is this all based on your own walks in nature?

I live on a farm, and I’m immersed in nature all the time, but I think what’s particularly interesting is that nature writing doesn’t exist in the Welsh language as a form, and yet the connection is somehow still there. We’re in lambing season at the moment, and you will see crows circling lambs and taking their eyes and tongues, and that is as much a part of nature as the spring flowers and all the beauty that happens at this time of year, and that gives you a clear picture of the duality of nature. What I also wanted to do was to put back story and language into the natural world, because there have been so many books that seem to portray Wales and its mountains as empty and barren, and of course they’re only empty if you’re culture-blind or language-blind.

‘By-the-wind sailors’ is such an evocative name. I’ve not heard of them before. Just how often do they float in on the tide?

It’s a seasonal thing. There’s a stretch of coast where things tend to come in, it’s something to do with the tides and the shape of the coast, and it’s fascinating because each cove is different, and I think if this book is anything, it’s a celebration and an appreciation of difference, and the preciousness of difference.

Hamza reassures Nefyn: “I’ve seen how people treat each other in this world… You received me without judgement. With kindness. With acceptance. I think that maybe you are well. It is everyone else on this earth that is sick.” Did you set out to make this kind of non-judgemental compassion in adversity (and its opposite) the key message in the book?

I think so, and unfortunately it seems even more relevant than when I wrote it, with what’s happening in Ukraine. I think we’re encouraged to think in broad strokes, to pull back and make generalisations about peoples. But when you get to the nitty-gritty, when you get to the one-to-one, it’s often about kindness, and it’s often about our common humanity, when you’re looking in the whites of somebody’s eyes. And I think the book encourages us to look at the specific and the microcosm, rather than pulling back and making sweeping statements, which is what our politics is about at the moment.

Hamza also maintains, “A map is just a way of thinking about the world, but it can sometimes tell you more about the one making it than anything else,” and points out that military drones such as those tested at the base can give a surface snapshot, “but to map a place properly, you must feel it. Know it. That is what they do not understand.” It’s an example of how information technology, counter-intuitively, can take us further away from deep knowledge and understanding.

I talked to an Army expert who’d been out in Syria and various places in the Middle East, and he was saying they would often buy maps off local people. It seems quite a rustic way of going about it, when they’ve got all this sophistication and technology, but it’s actually knowing a place that they’re missing completely, and that’s what war does.

Joseph’s journey is to maturity, and an appreciation that letting somebody have their freedom is a remarkable act of love, rather than what he’s been taught through his life by his father, who captured and stifled his mother.”

When he feels he’s losing Nefyn, Joseph recalls his failed attempt as a child to save a storm petrel with a broken wing, and reflects that he should have learned by that “how futile it was to intervene in fate.” But it’s Nefyn’s intervention that gives Hamza a new chance, so is Joseph’s thinking flawed in that respect?

Joseph is deeply conflicted, and he has somehow conflated preservation with protecting and stifling, he can’t see the difference. Because we can make moves to protect people without snuffing their life force out. I think Joseph’s journey is to maturity, and an appreciation that letting somebody have their freedom is a remarkable act of love, rather than what he’s been taught through his life by his father, who captured and stifled his mother.

You’ve written eleven novels for adults and many other books for children and young adults, all in Welsh. Why did you want to write this story in English?

Many reasons. One of them was I just wanted to broaden out a little what people think of as Welsh writers. There are so incredibly few Welsh language writers that also write in English – you can probably count them on a few fingers, it’s not even a hand. And I just thought it’s important for us to have that representation, and that we are seen, because with writing in a minority language comes the inevitable invisibility. There were also tropes around Wales and Welshness that I wanted to fight against a little in this book. There’s a really damaging view of Welsh language-speaking Wales as insular and inward-looking, and of course that’s not true. I look at my children and their friends and they have five languages between them, but Welsh is the one they share every day, they live their lives through Welsh. And I think it’s significant that the parts of Wales that speak the Welsh language also voted to stay in Europe. There’s an affinity with small countries with multiple languages, when you think of Catalan or other languages that are living side-by-side with dominant languages. So it was about representation, it was about also me exploring another side of myself, because as a writer you are always curious. I have a book coming out next month as well with Macmillan for middle-grade which is nothing to do with Wales or Welshness, so it’s about stretching your muscles as a writer as well. Also I wanted to give back to the culture that has given me so much – my work is on the A-level syllabus, and it was important to me to create a body of work in the Welsh language that would hopefully stay a little while, or be some kind of contribution. Then when I turned 40 I had a little bit of a crisis, and I decided – because I have written a lot, and I started writing quite young – I wanted to find what else I could do. And to be present in conversations, to be visible in conversations I think is important as we develop as a nation.

If you walk out at Borth at a certain tide time and a certain time of year, you can see the petrified forest out there.”

Derceto (also known as Atargatis or Siriadea), from Oedipus Aegyptiacus by Athanasius Kircher, 1652. Wikimedia Commons

The incantation Nefyn uses to evoke the storm that enables Hamza’s escape is from a collection of Medieval Welsh manuscripts known as the Myvyrian Archaiology. Can you tell me more about it?

The whole forest under the sea that Nefyn takes Hamza to see is an old folkloric country that was just off the coast here, called Cantre’r Gwaelod. It was a beautiful, beautiful city, and the story goes that the king had a big party and the guardsmen at the door, who had to close the doors to keep the seas out at certain times of day, got drunk, and of course the whole city was drowned. If you walk out at Borth at a certain tide time and a certain time of year, you can see the petrified forest out there. So those lines are attributed to the king of Cantre’r Gwaelod, and it basically means that he doesn’t fear the wave, but he fears the power of the sea, in that there are certain things you can get over, but there is an existential other power out there that is going to get you. It’s about overwhelm. There’s quite a claustrophobic feel to the novel in many ways, and as you said, with the cottage almost falling into the sea, it’s a sense of cultures on the edge, pushed up to the edge, and you’ll find Welsh-speaking communities quite often pushed up against the side of the sea. It’s that fragility in the face of overwhelm that was also present in those texts. I just thought it sounds so beautiful, and it connects the Welsh part of the book with something deeper as well.

The characters’ names have an epic quality too. Can you tell me about your choice of Nefyn and Hamza?

Nefyn is a place in Wales, and it’s a place that is at the moment at the heart of quite a bit of political unrest because in Penllyn in general there have been lots of protests recently about second homes and young people unable to live where they’ve been brought up. Weirdly, having already come up with Nefyn as a name for her, I looked at the old texts of the mermaid stories, and the Mabinogion myths, and I found a mermaid called Nefyn, so it just felt right for contemporary reasons and also for ancient reasons.

And Hamza actually comes from a taxi driver in Aberystwyth who’s from Turkey. He drove me home one evening and we got talking about literature, and he went and bought one of my books, which of course was in Welsh, and then he learnt Welsh. He’s amazing, he’s become such a great cheerleader of mine and he comes to all my events. He ferries a lot of the Welsh students in town back and forth, and he always has copies of my books in the glovebox of his car. Again, it’s those chance encounters, that spark. There’s such a trope about chance encounters between cultures sparking friction, when in fact a lot of these things spark a common love of literature and language.

I’ve worked with screen for a long time, and I find it a brilliant antidote to when I’m writing novels and working on my own. I quite like then having projects where I’m working in a team, I find it balances me out socially.”

You adapted your novel Martha, Jac a Sianco for film and have written for the BBC/S4C thrillers Hinterland and Hidden. What’s next for you in film and TV, and are there discussions yet about adapting Drift?

I would love to be able to tell you, but I can’t at the moment. There are discussions, yes. I’ve worked with screen for a long time, and I find it a brilliant antidote to when I’m writing novels and working on my own. I quite like then having projects where I’m working in a team, I find it balances me out a little socially, because obviously I live somewhere extremely remote as well, so it is nice sometimes to have that contact. And there is a visual quality to the way I write. In earlier years I used to paint a lot, and I sold a few of my paintings, and I would love to get back into that too, but at the moment I haven’t got any creativity left after I’ve been writing all day. But yes there are exciting plans afoot, I can say that.

How did you go about working with Gwen Davies on the translations of Martha, Jack & Shanco and The Jeweller? And are translations of your other adult novels in the pipeline?

I’ve known Gwen a long time and she knows my work in Welsh very well, and that was a great starting point. She knows my sensibilities and my turn of phrase, my tone and my rhythm, that kind of thing. It was fairly seamless a process, because I’m quite a fan of letting somebody take ownership of a translation. I don’t like people looking over my shoulder when I’m writing, and I will not do it to other people. So we met up a few times, she asked me some questions, but you have to leave somebody to find a life for the book in another language. That’s why I tend not to translate my own work, because I’m too close, and I think there is a value in letting somebody bring their own experience to it. And similarly, and this is a strange thing for me, the middle-grade book that will be out next month has been translated into Welsh by my Welsh-language editor. So the Welsh version and the English version will be published on the same day, one with Macmillan and one with a small Welsh publisher, so the children who have read my work before can have the choice of Welsh or English.

I’ve known Gwen a long time and she knows my work in Welsh very well, and that was a great starting point. She knows my sensibilities and my turn of phrase, my tone and my rhythm, that kind of thing. It was fairly seamless a process, because I’m quite a fan of letting somebody take ownership of a translation. I don’t like people looking over my shoulder when I’m writing, and I will not do it to other people. So we met up a few times, she asked me some questions, but you have to leave somebody to find a life for the book in another language. That’s why I tend not to translate my own work, because I’m too close, and I think there is a value in letting somebody bring their own experience to it. And similarly, and this is a strange thing for me, the middle-grade book that will be out next month has been translated into Welsh by my Welsh-language editor. So the Welsh version and the English version will be published on the same day, one with Macmillan and one with a small Welsh publisher, so the children who have read my work before can have the choice of Welsh or English.

So could there be a Welsh translation of Drift?

Maybe, I don’t know. We’ll see. But it’s fascinating to be breaking new ground.

What are you writing next?

I have a few picture books in the pipeline, I have my next novel for Doubleday, which is well on the way. And there’s an exciting animation project as well, based on one of my little picture books, around bees. I’m a beekeeper, my daughter who’s ten keeps bees as well, so there’s an exciting project on the way there. I have three books out this year, and they were all two-book deals, so there will be three more texts coming up soon.

Lastly, after reading your book I really want to explore more of the Welsh coast. Have you got any recommendations?

Well, I would definitely go to Aberporth and Llangrannog. There’s a cafe in Llangrannog where you can have a lovely hot chocolate right on the beach, which I would highly recommend. And then north of Llangrannog there’s Cwmtydu, which is a place I used to be taken a lot, it’s almost like the cove in Drift, it has steep rises, there’s an old lime kiln just at the back of the beach, and there are just so many stories there. If you look for T. Llew Jones, who is the king of Welsh literature for children, he wrote many, many books about pirates and that area – Twm Siôn Cati (the ‘Welsh Robin Hood’), Barti Ddu (Black Bart), all these wonderful stories, I’m sure there’l be some in translation – and it’s a beautiful place.

Welsh people are celebrated for our hills and valleys, but we don’t see that much about the coastline somehow, which is strange. So to celebrate that a bit I would highly recommend. If you continue on there are quite timely villages along the way with a good stretch in between, and you could of course go to New Quay, Cei Newydd. Maybe avoid it at the weekend because of all the tourists, but you could go and have a drink where Dylan Thomas drank, and there’s some lovely seafood there and wonderful views.

Caryl Lewis is a multi-award-winning Welsh novelist, children’s writer, playwright and screenwriter. Her breakthrough novel Martha, Jac a Sianco (2004) is widely regarded as a modern classic of Welsh literature, and sits on the Welsh curriculum. The film adaptation – with a screenplay by Caryl – went on to win six Welsh BAFTAS and the Spirit of the Festival Award at the 2010 Celtic Media Festival. Her other screenwriting work includes BBC/S4C thrillers Hinterland and Hidden. She is a visiting lecturer in Creative Writing at Cardiff University, and lives with her family on a farm near Aberystwyth. Drift, her debut novel in English, is published by Doubleday/Transworld Digital in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Caryl Lewis is a multi-award-winning Welsh novelist, children’s writer, playwright and screenwriter. Her breakthrough novel Martha, Jac a Sianco (2004) is widely regarded as a modern classic of Welsh literature, and sits on the Welsh curriculum. The film adaptation – with a screenplay by Caryl – went on to win six Welsh BAFTAS and the Spirit of the Festival Award at the 2010 Celtic Media Festival. Her other screenwriting work includes BBC/S4C thrillers Hinterland and Hidden. She is a visiting lecturer in Creative Writing at Cardiff University, and lives with her family on a farm near Aberystwyth. Drift, her debut novel in English, is published by Doubleday/Transworld Digital in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

@DoubledayUK

caryllewis2

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

wearebookanista

bookanista.com/author/mark