Catching the tap-tap to Cayes de Jacmel

by Lane AshfeldtLucien pulls at bits of broken wood near his sore leg, hoping to hear the hard rattle of plastic. He found two bags of crisps here before, and some sweets. But that was a long time ago now. Two, three days? He’s been down here now, he doesn’t know how long. How do you tell when there’s no light and your phone battery is flat? Just inches away, there could be more food or drink that he hasn’t yet found. Best keep searching. No use being all skin and bone when they finally pull him out of here.

Lucien wonders how many other buildings toppled in the quake. He wouldn’t be surprised if this was the only one. The cinema was one of the older buildings in the neighbourhood, and it’s not like his boss invested much in maintenance: on a windy day the place had always looked ready to fall down.

He hears a noise from off to his left. Tap-tap.

“You still hanging on there, Luc?”

The old woman, Agnes, her voice a hoarse whisper.

“Oh yes, I’m not going nowhere.”

Each of them is trapped in a separate air pocket. He’s never seen Agnes, but since this thing happened Lucien’s got to know her voice. Agnes was watching a movie in the upper circle, so she must have dropped quite a way to be down here on the same level as him. Lucien was on the late shift, chalking next week’s movies on the blackboard – a weekly task he liked better than his real job, which was selling cinema tickets and popcorn, and cleaning up after the show. At first he thought he’d knocked the board over, then he realised everything was shaking and falling.

“You’ve been quiet,” Agnes says. “They’ve all been quiet awhile.”

On day one she had told him she could hear five or six people tapping.

“They’re resting,” he says. “Keeping their strength up for when we get out of here.”

Agnes doesn’t mention the ugly sweet smell that seeps in and mingles with the stale dusty air. Nor does he. Neither of them wants to think about that. Lucien knows he can’t reach her, but to cheer her up he says:

“If I find more bon-bons, Agnes, I’ll split ’em with you, I promise.”

“I’ll hold you to that,” she says.

And he knows he’s made her smile.

The smile in her voice reminds him of his mama. It’s a long time since he spoke with her. Months now. Lucien misses her voice. When he was little, after his father left for Port-au-Prince, Mama would talk with him at night until he fell asleep. If he closes his eyes it’s like there is no broken cinema on top of him. He’s standing in the sunlight by Mama’s house, breathing in fresh sea air. When this is done, if he gets out and walks away from this, he’s going home… He stops himself.

Not if. When. When he gets out of here.

She’s a strong woman, his mama. The night the hurricane blew the roof off, she made the children huddle together in the kitchen while the wind howled around them… Before dawn, the wind calmed and they slept.”

Mama’s doing fine, he knows it. In the little village outside Cayes de Jacmel where she lives, the buildings are small and light. Home is a single-storey house. No concrete floors to fall and trap her. Besides, there’s the timing: the quake came at the start of the evening shift. That time of day, Mama’s always out and about feeding the hens. The worst that could have happened is she fell over and picked herself up again.

She’s a strong woman, his mama. The night the hurricane blew the roof off, she made the children huddle together in the kitchen while the wind howled around them, little Rousseline crying and hanging on to her teddy bear to keep it from blowing away. Before dawn, the wind calmed and they slept.

When they woke, Mama was gone. Soon, though, they heard her voice from outside: “Luc, Zach, come quick and help me with this.” She had found the tin roof in some trees, and dragged it home single-handed. She battered the corrugated metal into shape and together they set it back on the walls, weighting it down with heavier stones than before. That’s how strong Mama is.

Lucien finds no more chocolate, but in this darkness a glimpse of the outside world is better than any sweet. He feels stronger, the pain in his leg less sharp than before.

When this is over he’s going to leave this damn ugly-beautiful city. It mesmerised him when he first arrived: the hustle like a hundred market days jammed together – too many people for him to know their names and remember their stories, like he did back home. But now he’s been here a few months, Lucien knows that Port-au-Prince and Cité Soleil are not so special as they seemed from far away.

Tap-tap bus, Carrefour, Haiti (detail). Jonathan Pankau/US Navy/Wikimedia Commons

He also knows he won’t be driving home in a 4×4 like he planned. That would have made Mama proud; she loves people to see how well her family is doing. But it would take years to buy a car like that, maybe more years than Mama has left. And she’ll be pleased to see him as he is. That’s good enough for him.

When Lucien told Mama he was going to the city, she cussed him for two days solid. She barely spoke to him the day before he left, but the next day she got up before dawn, made him breakfast and watched him eat it. She even walked to the edge of Jacmel with him, though she rarely left the house so early except to tend to her animals. He didn’t like to drag her up town at the crack of dawn, but he had to be there in good time in case the tap-tap* left without him. If enough people came it would leave by seven-thirty. If not, the driver would sit in his minibus smoking cigarettes until he sold enough seats to cover his petrol, then take to the road in the hope of adding a few more passengers along the way. That day Lucien was lucky. The tap-tap was nearly full, but not so full that he would have to stand on the runner outside, or sit up top.

All the way there, Mama hadn’t spoken. Only after he paid and took his seat did she reach in through the air vent carved in the side of the bus, take his hand and say:

“I’m worried you’ll be lost to us, Luc. I never once heard from your papa after he went to Cité Soleil.”

“I’m not like Papa. You won’t get shut of me that easy.” He leaned out of the opening, kissed her, and handed her his phone. “Look Mama, I need a new phone – you take this one. I’ll call you tomorrow, OK?”

She smiled as the brightly coloured bus moved away.

The tap-tap climbed noisily up the steep hill that overlooked the caye, and Lucien felt dizzy when he glanced down a few minutes later. From up here you couldn’t see their home – the whole village was hidden by greenery. Closer to town the long stretch of white sand was interrupted by fishermen’s huts, a wooden jetty, boats. At the place on the edge of town where the sealed road made a loop and came back, a few buildings stood out: the market, the petrol station, the church. The crowd gathered at the bus stop had mostly scattered, but Mama was still there in her bright pink dress, waving her scarf.

He almost asked the driver to stop then and went back. But he didn’t, he just leaned out and waved goodbye. He called her every night from Port-au-Prince until his old phone stopped working.

Lucien pictures himself telling his boss he has to quit. Then he grimaces, because after all, the cinema is lying in bits all around him. And who knows what’s become of his boss? Even if he wanted his old job back, he can’t have it.

Soon as he gets out of here, he’s catching the tap-tap to Cayes de Jacmel. When he gets there, Mama will lay out a homecoming feast to celebrate, dishes ranged along the bench in the backyard: fresh fish cooked in banana leaves, rice, fruit… Everyone will be there, all their neighbours, old Ernesto with his guitar and a song, and his dazzling smile. It will be like a wedding without going to church. And he is going to dance.

Some hours later when Lucien wakes up, he is cold. His legs are stiff and the one that’s been hurting feels like nothing at all. He taps the wall but no one answers, not even Agnes. For the first time he feels nervous. He remembers his grandma telling him how she saw the blinding white light that comes for people when their souls leave their bodies. Lucien was ten years old then, and was visiting Grandma in hospital. She fought the light off that first night, but it didn’t leave so easy. Two nights later it came for her again, and this time it took her away. This is what he’s thinking when the bright light comes for him.

Lucien shuts his eyes tight. He will not, he must not, see this light. The light of the dead people is not for him. He wants to live.

Tap-tap. “You see it?”

Lucien shivers at Agnes’s cracked whisper. He really thought she was gone this time. Maybe she belongs to the other place now, and has come to fetch him?

“See what?”

“You mean you don’t see that light?”

The light on his closed eyelids glows red. He hears another voice. The words are muffled. Then, something about body heat and survival rates. Lucien smiles and opens his eyes. This is another light. The world is not ending, it’s beginning again. Loud as he can, he shouts,

“Here, over here. We’re here and we’re alive.” And to Agnes he says: “Do I see that light? Yes, I see it, and it’s beautiful. What did we tell each other?”

Her voice is hoarse but bright with joy,

“We are getting out of here.”

* So named because people tap on the bus to signal when they want to get on or off.

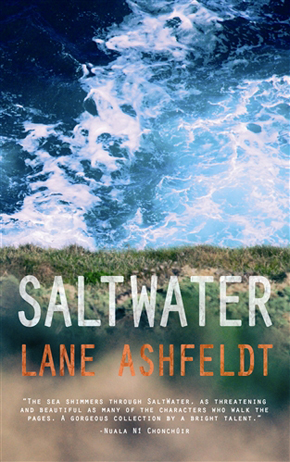

From SaltWater, published by Liberties Press.

Lane Ashfeldt’s stories have appeared in numerous literary journals and anthologies, and been performed at Bloomsbury Festival, WordFactory and West Cork Literary Festival. SaltWater is a collection of stories set in coastal areas around the world, from Sherkin Island in County Cork to the shores of New Zealand. Often inspired contemporary or historical events, they veer between family tragedy, the excitement of teen love and observations of daily life. Several of the stories have been shortlisted for or have won fiction prizes: ‘Catching the Tap-Tap to Cayes de Jacmel’ won the Global Short Story Prize, ‘Dancing on Canvey’ won the Fish Short Histories Prize, and the title story was shortlisted for the H.G. Wells Prize.

ashfeldt.com