Cocaine and other addictions

by Alexander StilleIn 1920, at the age of just twenty-seven, a young Italian named Dino Segre, writing under the pen name Pitigrilli, achieved overnight success and notoriety with a book of short stories called Luxurious Breasts, followed the next year by the novel Cocaine, and a second book of stories entitled The Chastity Belt.

Although he was branded by some as a ‘pornographer’, he would not be considered such by contemporary standards: rather than graphic descriptions of sex, Pitigrilli offered a deeply cynical, iconoclastic satire of contemporary European society.

Behind the official façade of bourgeois morality, traditional family life and patriotism, Pitigrilli saw a world driven by sex, power and greed, in which adultery, illegitimate children and hypocrisy were the order of the day and husbands and wives were little more than respectable-seeming pimps and prostitutes. Pitigrilli’s sarcastic, aphoristic style shocked and amused by turning conventional morality (and most of the Ten Commandments) on its head:

Never tell the truth. A lie is a weapon. I speak of useful, necessary lies. A useless lie is as unpleasant and odious as a useless homicide…

Do not covet thy neighbour’s wife, but if you do covet her, take her away freely. When in the theatre, on the tram or in a woman’s bed, if there is a free place, take it before someone else does…

Hate your neighbour as you love yourself: and don’t forget that revenge is a great safety valve for our pain… Believe me: a good digestion is worth much more than all the ideas of humanity…

Honesty, duty, brotherhood and altruism are like supernatural phenomena: everyone describes them but nobody has seen them; when you get closer, either they don’t happen or there’s a trick behind it… (The Chastity Belt)

Pitigrilli’s cynical amorality captured something of the spirit of Italy in the early 1920s, a society that emerged from World War I with many of its traditional beliefs in pieces. The calls to glory and sacrifice and national renewal had proven cruel illusions, with the death and mutilation of millions resulting in but a few minor territorial changes. Meanwhile, traditional pillars of society – such as the Catholic Church and the country’s economic and political elite – had lost much of their authority. Women were pushing for greater freedom and autonomy, challenging existing standards of personal morality and family structure.

Montmartre is the modern Babylon, the electrified Antioch, the little Baghdad, the Paradise of the cosmopolitan noctambulist, the blinding, deafening, stupefying spot to which the dreams of the blasés of the whole world are directed.”

In this tumultuous context, Pitigrilli’s books were quickly translated into numerous languages and he became an international succès de scandale. He then became the editor of a well-known magazine Le Grandi Firme, (The Big Names) the appeal of which was partly due to its daring content and cynical, worldly tone.

In Paris and Turin, Pitigrilli cavorted with society’s upper crust, which experimented with theosophy, occult séances, gambling and narcotics as means of replacing the old certainties supplied by church and fatherland. In Cocaine, perhaps his most successful effort at a sustained narrative, Pitigrilli describes a world of cocaine dens, gambling parlours, orgies, lewd entertainment and séances. His main character Tito Arnaudi goes to Paris and finds himself swept up in the post-war French metropolis:

Montmartre is the modern Babylon, the electrified Antioch, the little Baghdad, the Paradise of the cosmopolitan noctambulist, the blinding, deafening, stupefying spot to which the dreams of the blasés of the whole world are directed, where even those no longer able to blow their noses come to challenge the world’s most expert suppliers of love. Montmartre is the Sphinx, the Circe, the venal Medusa of the many poisons and innumerable philters that attracts the traveller with a boundless fascination.

The principal occupation of the characters of Cocaine is using narcotics, sex and alcohol to distract themselves from the horrors of real life. As Tito puts it at one point: “Life is a mere waiting room in which we spend time before entering into the void.” In searching for any kind of thrill or stimulation, they resort to “the fashionable poisons of the moment, the wild exaltation they produce, the craze for ether and chloroform and the white Bolivian powder that produces hallucinations.”

Tito, a failed medical student who has just been hired as a journalist, begins to investigate cocaine dens in order to write an article for a Paris newspaper appropriately named The Fleeting Moment. In the course of his research, he indulges in the white powder, which for a time acts as a kind of welcome balm, giving one “a sense not just of euphoria, but of boundless optimism and a special kind of receptivity to insults.”

As Tito’s lover, (or one of his lovers), Kalantan, tells him:

“There’s still hope for you… You haven’t yet got to the stage of tremendous depression, of insuperable melancholy. Now you smile when you have the powder in your blood. You’re at the early stage in which you go back to childhood.”

She spoke to him as to a child, though they were both of the same age. Cocaine achieves the cruel miracle of distorting time.

Kalantan is a wealthy Armenian woman whom Tito meets on the cusp of widowhood. A drug addict as well, she keeps a black coffin in her bedroom for making love. She explains her curious habit thus:

It’s comfortable and delightful. When I die they’ll shut me up in it forever, and all the happiest memories of my life will be in it… It also offers another advantage. When it’s over I’m left alone, all alone; it’s the man who has to go away. Afterwards I find the man disgusting. Forgive me for saying so, but afterwards men are always disgusting. Either they follow the satisfied male’s impulse and get up as quickly as they do from a dentist’s chair, or they stay close to me out of politeness or delicacy of feeling; and that revolts me, because there’s something in them that is no longer male.

Sex, like cocaine, provides only a brief distraction from life’s horrors, followed by disgust.

In the world of Cocaine and its main characters, life is a decorative mask with despair always just under the surface:

“Tell me why my heart goes on beating and for what purpose,” Tito asks Kalantan. “If you knew how many times I’ve been tempted to send it a little leaden messenger telling it to stop at once, because one day it will stop naturally, of its own accord, and why should it take the trouble of going on until then?”

Like sex, like drugs, Tito’s journalism is just another fantasy or hallucination meant to distract people from the horror of the world as it is.”

The outside world of work and industry is nothing more than another sham and a cheat. Another of Tito’s journalistic assignments, in addition to his cocaine reporting, is to cover the execution of a serial killer. Tito, exhausted after a night of debauchery, decides to write a purely fictional account of the event, including an ‘exclusive’ final interview with the killer and a gripping account of his death. When it turns out that the killer’s life was spared in a last-minute stay of execution Tito’s editor phones him in a rage over the embarrassment of publishing a false account. But the phony account is so wildly successful that the journalists for all the other papers are berated for having been scooped on such a dramatic story.

Like sex, like drugs, Tito’s journalism is just another fantasy or hallucination meant to distract people from the horror of the world as it is.

At a certain point, Tito’s two principal drugs, cocaine and sex, fuse in the figure of Maud, the main female character; Pitigrilli begins to call her Cocaine, since he becomes equally addicted to both at the same time. Maud too is a kind of addict, distracting herself by having sex with a procession of men, in some cases for money and in others for pleasure. She makes no effort to hide her activities from Tito, who follows her to South America in hopes of having her entirely to himself. The affair with Maud follows the course that addiction to cocaine generally follows: leading from initial euphoria to increasing desperation and psychological collapse.

When Tito finally does himself in, Maud and Tito’s best friend Pietro attend to him on his deathbed. Struck by Tito’s final despair, they vow to give up their lives of excess but all their intentions of turning over a new leaf fall away in just a few days when Maud and Pietro fall into bed with one another, ending the novel on a note of Pitigrillian cynicism, in which despair is leavened by bitter laughter. For all their apparent darkness, Pitigrilli’s books have a light tone and a quick and breezy air.

Cocaine appeared in 1921; the following year, Benito Mussolini and his fascist party came to power after the so-called March on Rome. Interestingly, Mussolini, himself a deep cynic and perhaps the shrewdest interpreter of the post-World War I mood, appears to have been a fan of Pitigrilli’s novels. When the books were attacked for their immorality, Mussolini defended them: “Pitigrilli is right… Pitigrilli is not an immoral writer; he photographs the times. If our society is corrupt, it’s not his fault.”

But as Mussolini’s fascism evolved from a transgressive, radical opposition movement into Italy’s new political order, Pitigrilli was bound to be regarded with increasing suspicion. Much of his withering sarcasm was directed at the patriotic and nationalistic nostrums that were the sacred gospel of fascism. In The Chastity Belt, Pitigrilli would write: “Fatherland is a word that serves to send sheep to slaughter in order to serve the interests of the shepherds who stay safely at home.”

Tito Arnaudi’s thoughts about patriotic duty, at least when viewed through fascist spectacles, are similarly blasphemous:

When I was twenty they told me to swear loyalty to the King… I took the oath because they forced me to, otherwise I wouldn’t have done it. Then they sent me to kill people I didn’t know who were dressed rather like I was. One day they said to me: “Look, there’s one of your enemies, fire at him,” and I fired, but missed. But he fired and wounded me. I don’t know why they said it was a glorious wound.

In 1926, Pitigrilli was put on trial for obscenity and narrowly acquitted. Perhaps sensing the need for political protection, Dino Segre applied – and was rejected – for membership in the fascist party in 1927 and 1928. Then one day in 1928, Pitigrilli descended from a train in his native Turin and was stopped by Pietro Brandimarte, a powerful local fascist official, who slapped him in the face and arrested him for alleged anti-fascist activities. Brandimarte had been the instigator of an infamous episode in the fascist seizure of power, the Turin Massacre, in which he and his squads murdered twenty-one anti-fascists just two months after Mussolini took over the government in 1922.

The case involving Pitigrilli’s alleged anti-fascist activities turned out like an episode in one of his novels, in which all the basest human instincts took on the mask of political principle and patriotism.”

But the case involving Pitigrilli’s alleged anti-fascist activities turned out like a bizarre episode in one of his novels, in which all the basest human instincts – greed, lust, anger, the desire for revenge – took on the mask of political principle and patriotism. What appears to have happened was this: some people eager to take over the editorship of Pitigrilli’s successful magazine, Le Grandi Firme, convinced one of his former lovers, the writer Amalia Guglieminetti, to destroy him. Guglieminetti was a society woman with literary ambitions, who dressed like a flapper and carried a long cigarette holder; she could have come straight off the pages of Cocaine. Guglieminetti had taken up with Brandimarte after her relationship with the writer ended, and she agreed to supply Pitigrilli’s enemies with personal letters written in his hand. These letters allegedly contained insults to Mussolini and fascism. But the forgeries were so crude that Pitigrilli was able to expose them at trial, forcing Guglieminetti to break down and confess on the witness stand.

Pitigrilli’s novel-like prosecution was the fulfilment of one of his deeply cynical injunctions: “To your friends and your lovers never leave in their hands any weapons they can one day use against you… The woman you love or who leaves you is your enemy; since all women are whores, including those who don’t get paid, she will tell her new lover, between one coitus and another, the things you told her, in great secret, between one coitus and another.”

Perhaps because of his sense of extreme vulnerability – or because his brand of cynical satire was less suited to the totalitarian thirties than the roaring twenties – Pitigrilli appears to have begun to work at ingratiating himself with the fascist regime. There is a document in the Italian state archives from 1930 that indicates he agreed to act as a police informant. In 1931, he sent a new book to Mussolini with the following dedication: “To Benito Mussolini, the man above all adjectives.

What is quite certain and well documented is that in the mid-1930s he became an extremely active and prolific spy of the OVRA, fascist Italy’s secret political police force. What makes his contributions especially intriguing is that he informed on a very rich and interesting circle of intellectuals and writers who would go on to become important parts of Italy’s anti-fascist cultural elite: the publisher Giulio Einaudi, Leone Ginzburg and his future wife Natalia, the painter and writer Carlo Levi, and the circle of Adriano and Paola Olivetti. Pitigrilli’s sudden usefulness to the secret police was sparked by a specific event: the arrest in March of 1934 of a young Turinese Jew, Sion Segre, who happened to be Pitigrilli’s first cousin. Sion Segre had been caught trying to smuggle into Italy from Switzerland a raft of newspapers and leaflets of an organisation called Giustizia e Libertà (Justice and Liberty), the main non-Communist left-of-centre anti-fascist group, whose leaders were living in exile in Paris. Following Sion Segre’s capture, fascist police arrested fourteen others suspected of ties to the organisation. Nine of the alleged conspirators were from Jewish families and some of the Italian newspapers reported the story by referring to a Jewish anti-fascist conspiracy, the first ominous note of an anti-Semitic campaign in Italy.

Why did Pitigrilli – or rather, Dino Segre – lend himself to such a distasteful operation, spying on his own first cousin and his friends? The answer is purely speculative, since Pitigrilli denied the charge till the end of his life – and, since Pitigrilli was never placed on trial, it was never proven in a court of law. (His son remains unconvinced to this day.) There is plenty of evidence of his spying activity, however; the official OVRA records lists him as Agent Number 373 and spy reports refer to events that make his identity clear. The victims of his spying confirmed that Pitigrilli was in fact the person with whom they had the various contacts described in the reports. As to motive, Pitigrilli’s own writings offer some obvious clues.

In an autobiographical book published after World War II, entitled Pitigrilli Parla di Pitigrilli (Pitigrilli Speaks About Pitigrilli), he reveals that he loathed his first cousin and the Jewish half of his family. Dino Segre was the illegitimate child of a Jewish father (also named Dino Segre) and a young Catholic mother. His father did not marry his mother until their child was eight years old. His father’s well-to-do Jewish family never fully accepted Pitigrilli’s mother as a daughter-in-law and did not treat the illegitimate product of their union – the younger Dino Segre – as a true grandson. Pitigrilli’s description of his father’s family is laced with deep, anti-Semitic hatred.

I was eight years old when my father and mother married and all the Jewry descended on my house: my grandmother, aunt, the crazy uncle, my cousins. My mother opened her living room to a flock of petulant, know-it-all parrots related to my grandmother, my aunt and uncle, who tolerated my mother from a distance, and bent over me with their disdainful nostrils, asking me to name the capital of Sweden, in order to show that if one doesn’t have the benefit of circumcision one cannot know what their sons know.

In The Chastity Belt, Pitigrilli would make the following claim:

Bastards should be considered as an elect, privileged caste… like the Japanese samurai… All men should be bastards so that they care for no one and are attached to nothing. The bastard! What could be more beautiful in the world than to be a bastard so that one can despise everything without making an exception for one’s own father and mother?!

Clearly, his early experience as an illegitimate child – with a deep desire to avenge himself on the supposedly more respectable world that snubbed him and his mother – was highly formative. The idea repeatedly appears in his writing that illegitimacy is proof that life itself is fundamentally a mistake, and proof too that ‘respectable’ society is nothing but a hypocritical lie: “One is born almost always by mistake.”

In some sense, Pitigrilli almost certainly regarded his spying activity as strangely consistent with the nihilistic cynicism that he articulated in his books – hating your neighbour as you love yourself, revenge as a safety valve, the celebration of lying. Pitigrilli reserved his most withering cynicism for those high-minded people who actually imagined that they were acting out of principle. A character in the novel L’esperimento di Pott (published in English in 1932 as The Man Who Searched for Love) remarks, “I am afraid of incorruptible people. They are the easiest to corrupt. Corruptible people have their price: it’s only a question of the amount. Sometimes, luckily, the price is so high that no one reaches it. But incorruptible people are really dangerous, because they… are corrupted not by money but by words.”

This is almost certainly how the anti-fascists of Giustizia e Libertà would have appeared to Pitigrilli: young, idealistic people who were ready to face prison for their ideas and who also tended to look down on a popular writer like Pitigrilli as not altogether serious.

After Sion Segre’s arrest, Pitigrilli approached some of his cousin’s friends and offered to help them. As an internationally acclaimed author he travelled frequently to Paris, where the leaders of Giustizia e Libertà were based. Pitigrilli was thus in a perfect position to act as a kind of courier between the base in Paris and its membership in Turin without attracting suspicion. The Italian customs officials frequently asked him for autographs rather than closely inspecting his bags when he re-entered Italy. Interestingly, there was some debate among the GL people about whether they could trust Pitigrilli. Some of them suspected him because of his ‘immorality’.

Pitigrilli was handsomely paid for informing, but for one who regarded all activities as a camouflaged form of prostitution, this would not have represented a problem of conscience.”

In fact, Vittorio Foa, one of the young men whom Pitigrilli spied on, noted that one of the older members of their group did object to Pitigrilli because of the immorality of his books. “We thought that was very funny at the time, but maybe he was right,” Foa told me fifty years after the fact. Pitigrilli’s cynical epigrams may have served as a kind of justification for his spying activities: “What could be more relative than an idea? A man is a traitor or a martyr depending on whether you look at it on one side of the border or another.” In retrospect, Foa surmised that Pitigrilli may have been motivated by a kind of perverse instinct, “the pleasure of doing harm to others.”

Pitigrilli was also handsomely paid for informing, six thousand lire a month, several times the value of a typical salary. But for one who regarded all activities as a camouflaged form of prostitution, this would not have represented a problem of conscience.

Pitigrilli’s career as a spy peaked in 1935, the year in which his secret reports led to the arrest of Foa and some fifty other suspected anti-fascists, many of whom, like Foa, spent the next several years in prison. Pitigrilli suspected that his great triumph might diminish his power as a spy. He actually suggested to the fascist police that he too be arrested with the others to deflect suspicion from himself and retain his utility as an informant. The police did not follow up on this suggestion and word trickled out from those in prison that Pitigrilli had been the traitor.

In 1936, the fascist regime began to prevent the reprinting of most of his books and in 1938 Pitigrilli, who had informed on his cousin, possibly motivated by powerful anti-Jewish resentment, himself fell victim to the racial laws passed by Mussolini. A note from the fascist secret police in 1939 states: “We thank you for all you’ve done up until now for us, but given the present situation we are compelled to renounce your further collaboration.” For the purposes of the fascist bureaucracy, he was thenceforth known as “the well-known Jewish writer Dino Segre, alias Pitigrilli.”

Even though Dino Segre was only half Jewish, his situation was made worse by the fact that, as a young man, he had married a Jewish woman, with whom he had had a child. Because divorce was not legal at that time, they were still technically married, even though Pitigrilli had long abandoned both mother and child. In order to improve his circumstances, Pitigrilli/Dino Segre consulted a female Catholic lawyer named Lina Furlan, who succeeded in having his marriage annulled. As Furlan explained many years later, the Church’s position was that since the marriage had occurred outside of the Church, it had never actually existed as a marriage. Among those whom Furlan consulted was the Vatican’s deputy Secretary of State, Monsignor Giovanni Battista Montini, the future Pope Paul VI. “Montini told me that as far we’re concerned there has never been a marriage, it was only a concubinaggio (living in sin).” After obtaining the annulment, Pitigrilli then married Lina Furlan in a church in Genoa on 26 July 1940.

This did not change his status with the fascist government and he continued to write self-pitying letters to Mussolini pleading for recognition as an Aryan so that he could work freely.

Rome, 25 March [1942]

Duce,

I understand that my little personal troubles are irrelevant to the great historical drama of the moment. But since you, with a word, can resolve my situation… I ask you to consider it: you will see at first sight that my request for recognition of belonging to the Aryan race is legitimate, since I have all the requisites required by the law.

Remove me, Duce, from this unjust, degrading and paradoxical situation, in which I am forced to work in secret, to suffer the pettiness of rivals and to continue boring you with my tedious tale…

Pitigrilli

Pitigrilli and Lina fled to Switzerland at the time of the German occupation and after the war he emigrated to Argentina, that refuge of many fascists and Nazis fleeing possible arrest and punishment. Later in life, he drifted back to Italy, but his reputation had diminished to the point that almost no one noticed. He died in 1975 in near total obscurity.

There was no place for Pitigrilli in a post-World War II culture that was dominated by anti-fascism and by some of the very men and women – the Ginzburgs, Levis, Olivettis and Foas – on whom he had spied. And yet in retrospect, Pitigrilli is a highly emblematic forgotten figure, a poète maudit of Italy of the 1920s; his cynical comic satire describes the disillusioned world that followed World War I and proved fertile for the triumph of fascism.

Reproduced from the afterword to a new edition of Cocaine by Pitigrilli, translated by Eric Mosbacher and published by New Vessel Press. Read more.

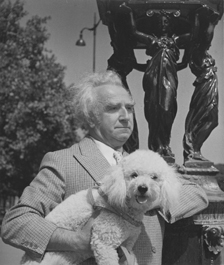

Alexander Stille is author of Benevolence and Betrayal: Five Italian Jewish Families Under Fascism and The Force of Things: A Marriage in War and Peace. A frequent contributor to The New York Times, The Boston Globe, The New York Review of Books and The New Yorker, he is the San Paolo Professor of International Journalism at Columbia University.

Alexander Stille is author of Benevolence and Betrayal: Five Italian Jewish Families Under Fascism and The Force of Things: A Marriage in War and Peace. A frequent contributor to The New York Times, The Boston Globe, The New York Review of Books and The New Yorker, he is the San Paolo Professor of International Journalism at Columbia University.