Coming of age novels

by Sarah Bannan

“A superb debut novel.” – Colum McCann

These books have nothing and everything in common. They come from different times, different genders. Their stories are as diverse as the way they are told. Some were written for adults, some for young people. The windows they provide into adolescence are varied, each refracting something distinct.

But then: there are the first loves, the kisses, the dances. (They always have a dance.) Young people playing as adults. Or playing as children. It’s never quite clear.

There’s the sitting around. The driving around. Boredom and fascination. The suburbs. The small town. Occasionally, the city. The presence of rumour. The irrelevance of adults. The attraction of the outside world, the comfort of what we know.

This list is not definitive. What list of top tens ever is? I’ve deliberately left out titles like The Catcher in the Rye and Lord of the Flies because, well, you knew those already. And maybe you know most of these. But maybe not.

I wanted a list that reflected older and newer experiences of adolescence. From male and female authors. Books that come at adolescence from different angles, sometimes straight on, sometimes more obliquely. Novels that see coming of age as a phase in your teens, those that see it a little later, in your twenties, fading into your adulthood.

These are novels I love. These are novels that have stayed with me. I remember where I sat (or stood or walked) when I read them. How I felt. The impressions that these books left on me. They shaped the way that I understand adolescence. The way that I understand humanity. They shaped what I read and how I read. What and how I write. And that’s what only truly great fiction can do.

“I am going to take a heroine whom no one but myself will much like,” said Jane Austen before writing Emma. A woman of twenty. Too smart with too little to do. In a place where gossip is currency. Where the “people of Highbury have little to amuse themselves with except the people of Highbury”.

I read Jane Austen in a frenzy in my teens. I came back to her work as an adult and saw the brilliant, sparkling prose that lay behind the brilliant plotting. I saw that Austen was an author taking risks, mastering her form, growing and breaking new ground with every work.

Emma is my favourite Austen novel. Emma Woodhouse is as clever as Elizabeth Bennett, but she is spikier, meaner, more flawed, and thus more fully realised. Austen gives us access to Emma’s intimate thoughts and desires. But, through admission to these same thoughts, the reader sees that Emma is an unreliable witness to her own sense of self. She is as human as the rest of us. And, because of this, Austen has created an enduringly fascinating heroine.

Maggie Cassidy by Jack Kerouac

Maggie Cassidy by Jack Kerouac

One of his Lowell novels, Maggie Cassidy is part fiction, part autobiography – a lyrical document of the memory – with an intensity and linguistic originality that could only come from Kerouac. At its best moments, the prose becomes music, full of aching and longing and passion and joy. Impressionistic, Maggie Cassidy is a half-remembered story of what it is, what it was, to fall in love. To know love and squander it. How life’s disappointments start early, and how foolish we are with one another’s feelings. He observes the tiny daggers that we send across to each other every day, when really we could just be sending love notes.

I’m always concerned with narrative voice when I read, and in Maggie Cassidy the first person narration is dropped for the final chapters when Jack, our hero, is no longer an adolescent, when he has crossed the bridge from innocence to experience. Here we have a detached third person, incapable of the clear-eyed passion of his youth, already damaged by the tiny disappointments that characterise adult life.

The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides

The Virgin Suicides by Jeffrey Eugenides

Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides is equal parts haunting and hypnotic, funny and sad. The suburban town where the story is set is, in a way, the novel’s central character. But what stays with the reader, the reason the work has such a powerful impact – aside from the glittering language, the magnetism of the story – is the novel’s narrative voice. Told in the first person plural, The Virgin Suicides explores the nature of memory, adolescence and grief. The voice is unequivocally ambiguous. And teenage life in a small town is nothing if not that.

While the voice presents the reader and the writer with limitations, these limitations become a gift. The narrators can only convey what they know or think they know or remember or find. But their unreliability, the things that they forget, that they perhaps misinterpret – these restrictions are in themselves revelatory. The first person plural brings into sharp focus the way that we are shaped by our surroundings, by those around us. How much of our identity is bound up in ‘us’ and ‘them’. Particularly when we are young.

I read The Virgin Suicides during my first year of college, when memories of my small town and the banal and bizarre rituals of my high school days had started to both solidify and blur in my memory. Eugenides proves that there is meaning in suburban life, that it is a territory worth exploring, in all of its quotidian and shadowy detail. Part meditation, part page-turner, the novel is a contemporary masterpiece, and it’s a book that I have returned to again and again.

I can remember being two hours and twenty minutes late for work on a cold morning in 2005, the year that Prep was published. Instead of clocking in at 9 am, like the good public servant I normally am, I stayed glued to my seat in Bewley’s on Grafton Street with a pot of lukewarm tea, utterly incapable of pulling myself away from Sittenfeld’s brilliant, brilliant first novel. The jacket had warned me. I remember this. It said that said Prep was “addictive as M&Ms”.

But it’s more than that. It’s sharp, incisive and cutting – with important things to say about passivity, adolescence, class and race. Don’t let that put you off: it says everything obliquely, nothing is didactic or on the nose. The novel’s protagonist and narrator, Lee Fiora, is a kind of contemporary, less privileged Holden Caulfield. And she’s neither as lame as she’d have us believe, nor as cool as she yearns to be. Instead, she occupies this important place in between. She’s the passive observer, the girl on the brink of being just popular enough. Lee is painfully obsessive and selfish but the reader senses, or hopes, that she is on the road to developing stronger character, on the cusp of gaining real empathy.

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Díaz

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Díaz

There is the small, perfectly formed novel. And then there is the large, electrifying, zig-zagging, hilarious, heartbreaking, perfectly formed novel. The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao is the latter.

“You really want to know what being an X-Man feels like? Just be a smart bookish boy of color in a contemporary US ghetto.” Oscar is a hero with a difference: fat, nerdy, comic book- and The Lord of the Rings-obsessed, Dominican. He is in direct opposition to one of the novel’s other leading men – Yunior – who seems to embody traditional Dominican masculinity. We root for Oscar, we feel for him, we cringe. And alongside Oscar’s story, we are brought into a larger history, one that reminds us we are not the sole architects of our identities. There is a limit to what we can control. There are forces that stymie our move from childhood to adulthood. We are shaped by the world, the politics, the culture, the history that surrounds us. Sometimes it seems like those forces might just swallow us up.

A Gate at the Stairs by Lorrie Moore

A Gate at the Stairs by Lorrie Moore

Our narrator for A Gate at the Stairs is Tassie Keltjin: curious, witty and warm. The novel charts her 20th year, an age chosen by Lorrie Moore because she viewed it as “the universal age of passion”. For Tassie, it is the year in which she moved away from home, attended a small, liberal arts college, worked as a nanny for an affluent couple, fell in love for the first time.

Tassie, as we find her, is on the cusp of forming her character. On the brink of becoming her solid, adult self. It’s not clear if she wants this and, as a reader, we’re not sure about it either. Because the adult world that she’s entering is complex and hurtful. And a twist of fate, an accident, anything at all: it can derail a person. A family. A life. Over the course of the novel, Tassie sees the limitation of love. She sees the capacity for hurt.

Moore renders the voice and the world beautifully, creating in Tassie one of the most convincing and empathetic characters in contemporary fiction. This is a big novel, complex and eventful, with heartbreak around almost every corner. But this is intercepted, of course, by Moore’s celebrated wit and her ingenuous punning.

Playing around with a range of registers, a panoply of voices, Paul Murray sends the reader diving into a fictional boarding school in South County Dublin. Posh and privileged and all deeply flawed, his cast of characters are preoccupied with standard teenage angst: girls, dances, mental health, video games and, ahem, String Theory. (There are plenty of flawed adults in this novel, too, and they remind us that we’re not so far away from our teenage selves.)

Told over three parts, Skippy Dies is complex, layered and richly detailed. It examines, only ever indirectly, the problems of the boom, the remnants of the Catholic Church in Irish life and what it means to be young and only half-independent. It is peppered – or maybe littered – with good and bad jokes (teenage boys can be ever so crude). And, as a narrative, it is deeply compelling.

No one is one-dimensional in this world, thanks to Murray’s ready command of voice and his willingness to take risks. All of them pay off. Skippy of the title dies on page one, in the novel’s prologue. When I learned, much later, the details of Skippy’s death, it actuality came as a genuine surprise to me. I remember coming into my book club and saying to people: “Skippy DIES?” My reaction, which was shared by the entire group, was proof that the novel had done something real and rare to me: I faithfully believed in these characters, I cared about them acutely. My disbelief was wholly suspended and I was absorbed.

Millions of people have vanished. Nobody knows why. Several years later, the people of Mapleton, NY are still struggling to put their lives back together. Struggling to make sense of the senseless.

Tom Perrotta, as evidenced through Little Children, The Abstinence Teacher and Election, is a master of the relationship between adult and child. Between adult and teenager. The way that these dynamics are strange and tested, and sometimes upended.

Through the eyes of Jill Garvey, we watch a teenage girl struggle through her final year of high school in a set of circumstances stressed to the limit: minus her mother, minus her brother and, in a sense, minus her father. We watch her brother struggle to understand his identity, and we watch her father and mother struggle to understand themselves without the comfort of their family, the comfort of what they once knew.

This is another suburban novel, in a place that is recognisable in its structures – the school, the church, the government. The book’s power lies in the fact that this world is so relatable – it is told on the exact right scale – to allow us to imagine ourselves in circumstances that are otherwise unimaginable.

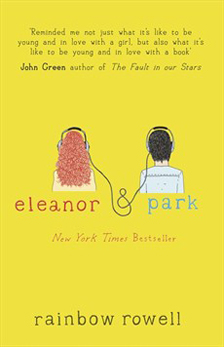

Eleanor and Park by Rainbow Rowell

Eleanor and Park by Rainbow Rowell

High school. A place of heightened expectation and few surprises. In my time, we trudged into our homerooms, experienced each day and left, vaguely disappointed, dimly aware that our school was a washed-out imitation of a cool school you might find in a movie or on TV. If the movies were Technicolor, then we were Donna Reed grey. We wanted things to be exciting, and we wanted some surprises, but they were never there. Not really.

In Eleanor and Park we’re introduced to a town, a school, young people, adults. Most are dull. Some are full of menace. All are filled with prejudice, both malignant and benign. And then Eleanor meets Park. Park meets Eleanor. Everything brightens, for a minute, as our heroes share their earphones, a few comic books, kisses. Rainbow Rowell asks us to open our eyes. To allow ourselves to be surprised by someone else. By their cuteness. By their music. By their complexity. Their humanity.

This is a story as authentic as they come, and as open and big-hearted. But there’s no sentimentality here, either. Eleanor and Park is funny and sharp. Sometimes very, very dark. It’s a book that dares you to look directly at the person opposite you, or beside you, or across the bus. It dares you to look at them. And really see them.

The Interestings by Meg Wolitzer

The Interestings by Meg Wolitzer

“You want to know whether the problems that you teenagers feel – will they follow you over the rest of your lives? Will your hearts always be aching? Is that what you are asking me?”

And the answer, from a camp counsellor, on page 131 of Meg Wolitzer’s extraordinary novel, is a resounding “YES”. Yes, these teenagers’ hopes and hurts and aches will follow them through their whole lives, no matter how much they feel they grow and change. They will still find themselves drawn back to this time when they were young. Whether life treated them cruelly or kindly then, they will carry these years, and one another, into adulthood.

Meg Wolitzer’s 2013 novel is an expansive portrait of the lives of six young people, brought together by Spirit-in-the-Woods, the type of summer camp I’d never heard of, but now wish I’d attended. With shifting points of view and time frames, Wolitzer sees her characters through high school, college and adulthood, and examines the impact of cause and effect. This novel is exhilarating, entertaining and poignant – and it’s hard to imagine a more nuanced picture of adolescence and adulthood than what is found in the novel’s 500-some pages.

Sarah Bannan was born in 1978 in upstate New York. She graduated from Georgetown University in 2000 and then moved to Ireland, where she has lived ever since. She is the Head of Literature at the Irish Arts Council and lives in Dublin with her husband and daughter. Her debut novel Weightless, about fractured young lives in Adamsville, Alabama, is published by Bloomsbury Circus. Read more.

Sarah Bannan was born in 1978 in upstate New York. She graduated from Georgetown University in 2000 and then moved to Ireland, where she has lived ever since. She is the Head of Literature at the Irish Arts Council and lives in Dublin with her husband and daughter. Her debut novel Weightless, about fractured young lives in Adamsville, Alabama, is published by Bloomsbury Circus. Read more.

@sarahkeegs

“An engrossing and sophisticated literary thriller, inspired by modern daemons from cyber-bullying to our recklessness in giving away our privacy online” – GQ

Author portrait © Bryan O’Brien

Read the opening chapters from Weightless: