Cretan love song

by Jim Shepard

“Full of wit, humanity and fearless curiosity… It’s a hell of a thing to walk the earth with Jim Shepard.” Joshua Ferris, Guardian

Imagine you’re part of the Minoan civilization, just hanging out with your effete painted face down by the water’s edge on the north shore of Crete, circa 1600 BC. Biting flies knit the breeze around your head. Wavelets slap discreetly ashore. When the volcanic island of Thera detonates seventy miles to the north, the concussion, even where you’re standing, knocks passing waterfowl out of the air. Oxen are jolted to their knees.

Back where Thera used to be, more than thirty-five cubic miles of the equivalent of dense rock have been blown out of the water and up into the troposphere. That’s all of Manhattan and the bedrock beneath it concussing upward thirty thousand feet. It’s as if something has convulsed the horizon and churned the bowl of the sky above. What you’re looking at no one in recorded history has ever seen, before or since.

Long before the blast column has reached the upper atmosphere, the shock wave coalesces in a grim line that radiates from the outer edge of your field of vision all the way to your little inlet. The oxen, still on their knees, low in terror and struggle to regain their footing. Your boy – your primary responsibility – seems to have slipped from your grasp. Everyone just gapes while the surge flashes across the last of the distance, and when it hits you’re knocked flat like the oxen, the palms above and around you stripped of their leaves in a roaring turmoil of wind and sand.

The woman beside you is on her hands and knees. The infant she’d been holding is facedown and crying nearby, at the end of a swaddling cloth that apparently unspooled in the impact. One ox is up and lumbering inland.

Off the beach a dark blue band races like a furrow back out to sea. Your boy calls to you, through air alive with grit and glittering in the sun. He has only one eye open, which may make the view a little less painful.

Once the undersea furrow finally aligns with the farthest edge of the sea it holds steady for a moment. Your boy is still calling. The infant is still crying. Then the horizon line darkens still more, and widens, all of this accompanied by a continuous rolling thunder that seems to emanate from somewhere beyond the curve of the earth. Another ox has gotten to its feet and bulled in panic past its handler. It’s only when you look to the east and west that you realize the band is widening because it’s rising, into a wave whose size is without precedent. At sixty miles away it already appears an inch tall, its upper edge frayed and filigreed in white. Its reverberations are already oscillating through your hands and feet. You have time to run, but unless you’re able to cover half the island in the next four minutes you might as well stay where you are.

She’s put wings to your feet for the entirety of your lives together, and with them you run. Your boy mostly keeps pace, clutching at your arm when you begin to pull away.”

Your boy finds you, since you’ve done so little to find him. He asks what’s happening. He asks what you’re going to do. He asks as if the very extent of your love and responsibility might carry with it sufficient power to avert even something like this. He reminds you that you have to run, and you understand him to mean that though you won’t reach safety you could maybe reach your home, his mother and your wife. In the interval you have left you might even make clear with just a moment’s embrace and the time to hold her face still and engage her eyes that despite your lassitude and arrogance and petulance and selfishness and pettiness, she’s granted you a gift for which you’ve never adequately expressed your joy. She’s buoyed and nurtured you and weathered your despotism, and continued to envision what you could’ve become rather than what you are. She’s put wings to your feet for the entirety of your lives together, and with them you run. Your boy mostly keeps pace, clutching at your arm when you begin to pull away. He’s the one who got you moving but is now receding, and you reach back your hand at his cry. The wave behind you is an all-enveloping sonic domain. The road before you is one you’ve traversed a thousand times. The woman waiting in the courtyard is your best chance to accomplish one more panegyric before the world upheaves and confirms that, whatever other self-renovations you may have had planned, your time is gone.

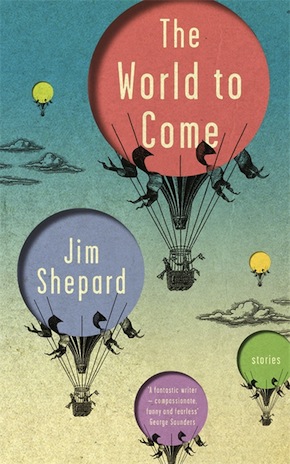

From The World to Come, out now in hardback and eBook from Riverrun

Jim Shepard is a National Book Award finalist and the highly acclaimed author of seven novels and five collections of stories including The Book of Aron (Quercus, 2015/Riverrun, 2016) and Like You’d Understand, Anyway (Knopf, 2007). He lives in Massachusetts with his family and teaches creative writing at Williams College. Widely acclaimed as one of the US’s finest writers, The World to Come is the first collection of his short stories to be published in the UK.

Jim Shepard is a National Book Award finalist and the highly acclaimed author of seven novels and five collections of stories including The Book of Aron (Quercus, 2015/Riverrun, 2016) and Like You’d Understand, Anyway (Knopf, 2007). He lives in Massachusetts with his family and teaches creative writing at Williams College. Widely acclaimed as one of the US’s finest writers, The World to Come is the first collection of his short stories to be published in the UK.

Read more

jimshepard.wordpress.com

Author portrait © Michael Lionstar

Read our interview with Jim Shepard around publication of The Book of Aron