Damn!

by Charles Portis If Sanford T.’s daddy hadn’t got killed that night I guess we’d still be with the carnival. What we was doing was hauling old man McClerkin around the country claiming he was Jesse James and charging fifty cents a head to come in and see him. We had to pay Mr Mooney thirty per cent of the take to travel around with his carnival but we was making good money anyway. That all come to an end the night Jesse got drunk and fell out of the Ferris wheel on top of a cotton candy stand. We tried for awhile having Sanford T. billed as Bob Ford but he wasn’t old enough to fool anybody and we had to close up. Mr Mooney kept us on to bark for the freak show but you talk about some hard folks to get along with, that’s freaks. We was about ready to quit anyhow when the alligator boy busted Sanford T.’s leg with a crow bar, something you might or might not expect out of a alligator boy. The carnival left us stranded in Montezuma, Arkansas, where Sanford T. was in the hospital and I guess that was the best thing that ever happened to us. The reason for that initial is that he’s got an older brother named Sanford too. His folks just liked the name I guess.

If Sanford T.’s daddy hadn’t got killed that night I guess we’d still be with the carnival. What we was doing was hauling old man McClerkin around the country claiming he was Jesse James and charging fifty cents a head to come in and see him. We had to pay Mr Mooney thirty per cent of the take to travel around with his carnival but we was making good money anyway. That all come to an end the night Jesse got drunk and fell out of the Ferris wheel on top of a cotton candy stand. We tried for awhile having Sanford T. billed as Bob Ford but he wasn’t old enough to fool anybody and we had to close up. Mr Mooney kept us on to bark for the freak show but you talk about some hard folks to get along with, that’s freaks. We was about ready to quit anyhow when the alligator boy busted Sanford T.’s leg with a crow bar, something you might or might not expect out of a alligator boy. The carnival left us stranded in Montezuma, Arkansas, where Sanford T. was in the hospital and I guess that was the best thing that ever happened to us. The reason for that initial is that he’s got an older brother named Sanford too. His folks just liked the name I guess.

I was setting on a bench in front of the courthouse reading Billboard when this old, weasel-eyed man comes up and sets down beside me.

“I hear you’re a carny,” he said.

“Well, you hear right, old man. Only I’m not working right now.”

“You got any money?”

I reached in my pocket and held out a half-dollar.

“Naw, naw,” he said, “I didn’t mean nothing like that. I’m the one what ought to be giving you a half. I want to talk business.”

“All right, start talking.”

“You innarested in making some money?”

“Now look, if you’re some kind of con man you ain’t talking to no farmer.’’

I finally pulled it out of him. He had a little place just outside of town where he bottled patent medicine and he wanted to sell out because his health was failing him and his doctor told him he better move out west if he wanted to live.

“How come you don’t take this medicine and save yourself a trip?” I asked him.

“Well, you see, that’s what’s wrong with me now. This is liver emulsifier, that’s what I call it, ‘Bethel Liver Emulsifier’, and my liver is so stout now that it’s overworking my other organs. I’ve got the liver of a 21-year-old boy, believe it or not. Of course you’re a layman and wouldn’t understand all about how it works. Has to do with bile flow and all that.”

“You got me there all right,” I said.

“And besides, my daughter out in California is about to worry me to death to move in with her. I’m willing to take a big loss on a quick deal.”

I could have everything, he said, including two fifty-five gallon drums of grain alcohol, which was the active ingredient, for $750. I picked up a bottle of the stuff off a table and smelled it. I couldn’t quite place the smell but it was the kind you don’t forget right away.”

I didn’t have nothing else to do so I rode out with the old man to look the place over. It was a old barn just off a gravel road and inside there was a bunch of bottles laying around and a big pressure cooker setting over a gas jet. I could have everything, he said, including a lease on the barn and the land and two fifty-five gallon drums of grain alcohol, which was the active ingredient, for $750. And that was just like giving it away. I picked up a bottle of the stuff off a table and smelled it. I couldn’t quite place the smell but it was the kind you don’t forget right away. It was kind of a dingy brown, like water that’s been flushed out of a car radiator.

“Go ahead and taste it,” he said.

I rolled a little of it around in my mouth and swallowed it.

“Damn!” I said, “that’s worse than green persimmons.’’

“That’s the alum and peanut oil you taste. Gives it a little body. It’s thirty per cent alcohol and that’s what makes you feel good. Takes a little while.”

I stuck the bottle in my coat pocket and told him I’d have to talk it over with my partner in the hospital. I didn’t encourage the old man any because Sanford T. and his daddy went broke selling mineral water before they hooked up with the carnival and I knew he’d just laugh about it. The old man already had his mattress strapped on top of his car and he was ready to make a quick deal all right.

Sanford T. was awful glad to see me that afternoon when I brought him the cigarettes and a Billboard and one of those magazines showing a big muscular guy fighting off ants on the cover.

“You know what the only thing they got to read in this hospital is?” he said, “Methodist Church magazines and Gideon bibles.”

“It’s a Methodist hospital,” I said. “If you was in jail they’d have detective magazines.”

“Yeah, and that’s something in their favor too. The doctor says I can get out of here in two more days. On crutches. I don’t know what the hell we’re going to do with me on crutches.”

I laughed and said we could go into the liver emulsifier business. I told him all about the old man and everything and he laughed too at first and then he cocked his head to one side like he does when he’s thinking.

“Wait a minute,” he said. “Thirty per cent alcohol. That’s sixty proof.” Then he started looking through all the church magazines on the table and found the one he was looking for and throwed it over to me. “Look at that map on the cover,’’ he said.

It was a WCTU Quarterly, and there was a map of the United States on it. It said something about the marching drys and all the dry sections of the country was in white and the wet in black. I didn’t know what he was getting at and I said, “So what?” He was getting excited now and he said, “Look at the south, man, it’s like Roosevelt and Landon all over again! You think we can’t sell sixty-proof medicine like hot cakes in every one of them dry counties?”

“If they knew what it was you might,” I said. “But you ain’t going to sell no liver emulsifier. Everybody and his brother is selling patent medicine now.”

“Then they ain’t selling it right. We’ll get the word around that our stuff has more alcohol than anybody else’s. We’ll get a catchy name and promote hell out of it.”

“You want I should buy the old man out, then?”

“Yeah, tell him you’ll give him four hundred dollars cash. He’ll jump at it.”

“As long as we’re going to sell it,” I said, “you might as well taste it.” I handed him the bottle and he took a pretty good shot of it.

“Damn! Phewwww. We got our work cut out selling that stuff,” he said.

“I’ll go along with that,” I said.

About that time this horsy looking nurse came in and told us to keep the noise down, other people’s in the hospital. “Okay, Miss Cakehead,” Sanford T. said. “We didn’t know we was disturbing anybody.”

She spotted the liver emulsifier on the table and marched over and picked it up.

“What is this, Mr McClerkin?”

“That’s tonic my friend here brought for my chills.”

“You never mentioned any chills to me.”

“I just didn’t want to put you out no more than I had to. This is awful good stuff, Miss Cakehead. Y’all ought to stock some of it in your medicine cabinet here at the hospital. Here, try it, it’s good for your disposition.”

She looked kind of suspicious like nurses do and took a small sip. She made a face like I never seen on a horse and rolled her eyes around and blinked like smoke was bothering her.

“Damn!” she said. “Damn!”

“That’s it, that’s it!” Sanford T. hollered and he must of woke up whoever was on the operating table. “That’s the name, ‘Damn!’ We’ll call it ‘Damn!’”

The newspapers and radio stations gave us some trouble at first on account of the name but we went ahead and let ’em use ‘Darn!’ and pretty soon everybody knew what they was talking about.”

We called it ‘Damn!’ all right and we made a pile of money doing it. The newspapers and radio stations gave us some trouble at first on account of the name but we went ahead and let ’em use ‘Darn!’ and pretty soon everybody knew what they was talking about. After it became popular they started using the name straight. They laughed and made jokes about the stuff but that was just more publicity. I think that one ad that Sanford T. wrote was what really sold it. Every time you’d turn on your radio you’d hear it:

“Damn if I don’t feel like I could rassle a grizzly bear, Martha.”

“And I, also John, thanks to ‘Damn!’ Like millions of other users we owe a debt of gratitude to the ‘Damn!’ folks for putting us back on the road to health and happiness.”

We had a lot of imitators too, but they was like gnats on a elephant’s back. One of them went us one better on the name business but we took it to the Federal Trade Commission and they made ’em change it because it was too similar to our trademark, ‘Damn!’ They wouldn’t have done any good anyhow on account of the people in the south are pretty touchy about someone using the Lord’s name in vain.

Where we messed up was overdoing a good thing. Sanford T. got this idea that if we doubled the proof we’d double sales. For awhile there, our customers was really on the road to happiness. The church folks started raising sand though and they finally put us out of business claiming we was selling untaxed liquor. Sales was dropping anyhow and the fad had just about run its course when we sold out.

Looks like we might be broke again before long. Sanford T. has sunk all the money we had left into promoting this hillbilly singer with greasy sideburns he picked up in Memphis. We had a good offer to buy into this traveling exhibition show with a stuffed whale on a flat car and a mermaid and a 1400-pound hog, which is a pretty damn big hog, but Sanford T. said this wasn’t the year for hogs. I told him it was always the year for hogs if they’re big enough and he said, “You’re so right,” but we didn’t buy it.

I’m not too keen on this singer. He can only play chords on a guitar and he’s got a little sinus trouble but, of course, that’s irrelevant to people who really like that kind of music. You ought to hear him sing sometime if you ever get a chance. You can’t hardly make out what he’s saying and he shimmies around like he’s got the tongues or something. Sanford T. says we got us another gold mine here if we play it smart but I think we’re going to wish we’d bought that hog before it’s all over with.

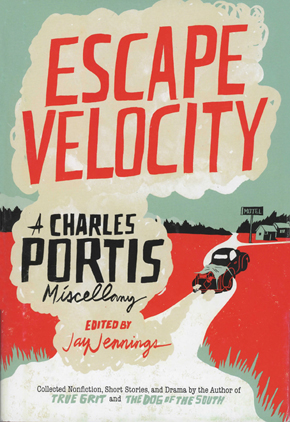

From Escape Velocity: A Charles Portis Miscellany, edited by Jay Jennings and published by Duckworth.

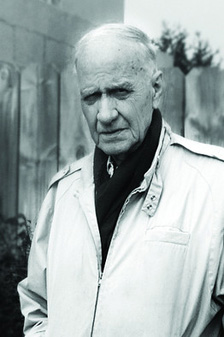

Charles Portis (born 1933) is best known for the novels Norwood (1966) and True Grit (1968), both adapted as blockbuster films. A former London bureau chief of the New York Herald-Tribune and writer for The New Yorker, he lives in Arkansas, where he was born and educated. Escape Velocity collects his journalism, short fiction, memoir and the play Delray’s New Moon, published for the first time, and covers topics as varied as the civil rights movement, road tripping in Baja and Elvis’s visits to his ageing mother. Read more.

Charles Portis (born 1933) is best known for the novels Norwood (1966) and True Grit (1968), both adapted as blockbuster films. A former London bureau chief of the New York Herald-Tribune and writer for The New Yorker, he lives in Arkansas, where he was born and educated. Escape Velocity collects his journalism, short fiction, memoir and the play Delray’s New Moon, published for the first time, and covers topics as varied as the civil rights movement, road tripping in Baja and Elvis’s visits to his ageing mother. Read more.

Probably the first short story published by Portis, ‘Damn!’ appeared in the October 1957 issue of Nugget magazine, when he was 23 and still attending the University of Arkansas. Nugget (“Entertainment in a Lighter Mood”) was a mildly racy publication in the Playboy mould, but with early literary pretensions; the same issue featured a short story by Grace Paley.