Deborah Levy finds her voice

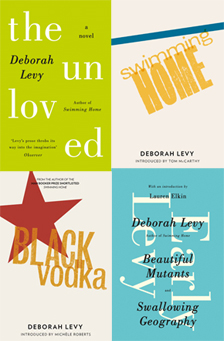

by Fiona Melrose Deborah Levy has been riding a wave since her novel Swimming Home was nominated for the 2012 Man Booker Prize. Both the novel and her superlative collection of short stories Black Vodka were published by indie publisher And Other Stories, while bespoke house Notting Hill Editions picked up her essay on writing, memory and childhood What I Don’t Want To Know, which is now published in a striking Penguin edition alongside her 1994 novel The Unloved and the novellas Beautiful Mutants (1986) and Swallowing Geography (1993). I fired off a string of questions via email and despite her voluble candour, was left wanting more…

Deborah Levy has been riding a wave since her novel Swimming Home was nominated for the 2012 Man Booker Prize. Both the novel and her superlative collection of short stories Black Vodka were published by indie publisher And Other Stories, while bespoke house Notting Hill Editions picked up her essay on writing, memory and childhood What I Don’t Want To Know, which is now published in a striking Penguin edition alongside her 1994 novel The Unloved and the novellas Beautiful Mutants (1986) and Swallowing Geography (1993). I fired off a string of questions via email and despite her voluble candour, was left wanting more…

FM: I have recently re-read your Essay ‘Things I Don’t Want To Know’. It struck me that it is so much about exile, both its pain but also the position of privilege it gives you in your adopted country, as a viewer, an observer. To what extent do you feel exile and displacement can be used to the writer’s advantage?

DL: I guess it means that language is our home… but most writers probably feel like that anyway? ‘Things I don’t Want To Know’ charts the turbulent journey from girlhood to adulthood as much as anything else.

Your story collection Black Vodka is all about exile and displacement, sometimes from love, sometimes from nationhood. Was this your intention or did the collection develop its own collective voice as you went? I ask as I am always struck by the strength of the book as a collection, not simply the merits of each story.

Black Vodka is also about men and women at war with each other – in every country and in every language! That’s what Greek myths are about too. But war is not interesting if love is not desired and searched for – though I’m not sure that love equals peace. Love is sometimes destructive – that is one of the themes in Swimming Home.

Some South African writers, or writers with some connection to the country, do not directly engage with its history, politics and current anomalies, but feel a certain pressure to address these issues eventually. Your essay is the first time you have alluded to those difficult years. How onerous was that, engaging with the things you don’t want to know?

The things I don’t want to know are usually the things I end up writing about. These are the things we know but don’t want to know we know. It was very challenging to write about my South African childhood. I asked myself, well, who would want to read this? There are many more interesting SA childhoods than my own. But my childhood had come back to chase me as a middle-aged woman in London and I no longer had the energy to run away! Hence the line: “If I wasn’t thinking about the past, the past was thinking about me.” As Freud told us, the repressed always returns, and when that happens it’s tricky to make The Past a cheese sandwich and tell it to catch a train to somewhere else. Also, I was hitching a ride on the four headings that Orwell identified to sum up his motivations to write. One of the headings is Historical Impulse. I reckoned that if I was going to steal another writer’s heading I should at least attempt to be truthful. So I wrote from a child’s point of view about growing up in apartheid with a family involved in the struggle, and how my voice disappeared when my father became a political prisoner for four years. And I wrote about the madness of adults who are supposed to make children feel safe. You know that phrase, you need a thicker skin? In some ways my childhood was not about having a white skin or a black skin, it was about not having a thick enough skin.

The things I don’t want to know are usually the things I end up writing about. These are the things we know but don’t want to know we know. It was very challenging to write about my South African childhood. I asked myself, well, who would want to read this? There are many more interesting SA childhoods than my own. But my childhood had come back to chase me as a middle-aged woman in London and I no longer had the energy to run away! Hence the line: “If I wasn’t thinking about the past, the past was thinking about me.” As Freud told us, the repressed always returns, and when that happens it’s tricky to make The Past a cheese sandwich and tell it to catch a train to somewhere else. Also, I was hitching a ride on the four headings that Orwell identified to sum up his motivations to write. One of the headings is Historical Impulse. I reckoned that if I was going to steal another writer’s heading I should at least attempt to be truthful. So I wrote from a child’s point of view about growing up in apartheid with a family involved in the struggle, and how my voice disappeared when my father became a political prisoner for four years. And I wrote about the madness of adults who are supposed to make children feel safe. You know that phrase, you need a thicker skin? In some ways my childhood was not about having a white skin or a black skin, it was about not having a thick enough skin.

Do you think you will ever write a South African novel or is that history too distant now? Or perhaps it is the opposite, it is still too dangerously close?

Never say never.

I was so struck by Kitty Finch’s predicament in Swimming Home, that women are reduced from being poets to being poems, complete, written onto the page by someone else, stripped of the agency of poetic creation. She is also naked much of the time, vulnerable and exposed, waiting to be written into each person’s version of her. Thinking about women as writers and the incredibly moving account in your essay of the softest of voices you had as a young girl and the process of finding a voice with which to speak out, are you frustrated that this is still a problem for women as artists?

Most artists of substance tend to get there in the end. It can be a tough journey for female writers because if we are skilled, we will walk our subjectivity into the centre of our work and make it blaze. By subjectivity I mean the ways we experience things in our minds. So why would that make things tougher for female writers? I do believe that the world and its arrangements (never in favour of women and children) still imagine there is one subjectivity and it is male – this mono-subjectivity is of course a delusion, but it’s hard to shift a delusion with rational argument! Subjectivity fascinates me more at the moment than words like sexuality or identity – though of course it is not detached from either. And so we have to speak up and say what we think and what we feel and chase our arguments. Writers are usually fired up and obsessed and at ease with spending so much time alone. Regarding Kitty Finch, my game was to give her an interesting mind. She is fragile and manipulative and often naked, but we are not able to easily dismiss the ways in which she thinks. Is she mad, is she sane – and what do those words mean?

I am always thrilled by how well-travelled your characters are. All of Europe seems to be their home. Your essay suggests that writers must travel, must strive to find new territory. How important is travel to you and your writing?

I am always thrilled by how well-travelled your characters are. All of Europe seems to be their home. Your essay suggests that writers must travel, must strive to find new territory. How important is travel to you and your writing?

I get a lot of energy from travelling. And I always keep notebooks. Right now, under my writing desk, I have three large boxes full of them. Sometimes when I’m writing a novel I take them out and usually there is something I need lurking in them. For Swimming Home I found the name of the street where Isabel encounters the blind Russian woman – and also the description of the city beach at night.

On the note of characters with frequent-flyer miles, what can you tell us about Hot Milk? The last we heard, a nervous man was stuck on a Ryanair flight, feeling increasingly itchy and uncomfortable. How is he, and when can we look forward to meeting him?

Aha, still writing this, to be published by Penguin in 2015. It is bad manners to my characters to reveal their souls before they have given me permission to do so. Hot Milk is about hypochondria – the flight into symptoms that replace spoken language. Susan Sontag wrote an interesting play titled Alice in Bed. It is about Alice James, sister of Henry, who in Sontag’s view, became a ‘career invalid’ rather than confront her own intellectual worth.

Imagine you were the head of a major arts body for a year, perhaps the British Arts Council, what would you do to help promote the short story, particularly in schools and education in general?

What about those moments when we are daydreaming on a bus and make up a totally brilliant speech in our heads to address the government or a lover or boss or teacher or someone who has wronged us? We don’t have to be writers to have written this sort of thing in our minds – in fact we often make corrections (editing) to give ourselves a better line than our opponent! I would ask for everyone in the land to submit these private speeches. Some of the best ones would be printed out and pasted on train stations, airports, supermarkets, banks, hospitals. Invite me to South Africa and I will get this project going.

Are there any books, novels or short-story collections that you wish you had written, that resonated with your core values and/or writing ambitions?

A collection I still hugely admire is Girls at War by Chinua Achebe. And I am thrilled by Gertrude Stein’s essay on Picasso and everything by J.G. Ballard and Marguerite Duras. I am also always moved by James Baldwin’s anger and exuberance.

Deborah Levy was born in South Africa in 1959 and moved with her family to London in 1968 after her father was imprisoned by the apartheid government for being a member of the ANC. She is the author of five novels and a number of acclaimed plays for stage and radio. She is currently Visiting Professor in Writing at Falmouth University.

deborahlevy.co.uk

Fiona Melrose completed an MA in Politics and Literary Criticism at Wits University, Johannesburg, and spent some time as a financial markets analyst in London before relocating to Suffolk to complete an MA in Creative Writing at Birkbeck, University of London and write her first novel. She recently moved back to Johannesburg and is represented by Jo Unwin Literary Agency.

Follow Fiona on Twitter: @PaperCutPrint