The dream of Norway

by Mika Provata-CarloneIn 1920, two years after the end of WWI, the League of Nations officially began its work of rebuilding the world. It was a grand scheme, a tremendous dream, a triumph of a reconstituted modernity, and the legacy of enlightenment humanism over militarism, colonialism, barbarity and tribalist divisionism. It should have been idealistic. It has been accused of being often ill-advised, partisan and disoriented, opportunistic or even immoral, a delusion rather than a dream. The League did not survive the war intact. It would be dissolved in 1946 in order to cede its place to the United Nations, bequeathing to it not only its hope and vision, but also its traumas, failures and lessons of disaster.

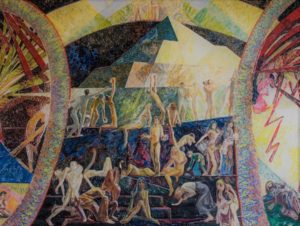

Perhaps the noblest part of this inheritance is strikingly and materially present in a vast mural, intended to encompass the ecumenical scope and ambitions of the League: the Norwegian Room in the UN’s Palais des Nations in Geneva features Henrik Sørensen’s monumental, multi-referential, multicultural and multi-prismatic The Dream of Peace, which was donated to the League in 1939 by the Norwegian government in a highly symbolic gesture defying time, the temporality of its historical moment, reality itself. 1939 was the League’s annus horribilis, as Germany invaded Poland, and the turning point when the construct of its ideas, its very sphere of influence, came under scepticism. Norway’s gift, in such a context, was not only a gesture of diplomacy but also a plea to all and sundry to heed the signs of darkness, against which Sørensen seems to have rallied an almost apocalyptic palette of colours and light. The mural is said to have been all but forgotten, according to Torild Skard, the granddaughter of Halvdan Koht, then Foreign Minister and Sørensen’s friend, who commissioned the work on behalf of the Norwegian government. Skard would initiate a process of rediscovery and rehabilitation of both work and artist. A commemorative plaque, ‘renaming’ Sørensen’s work, was added to the display in 2018, and during the ceremony Sørensen’s own words were cited with particular resonance: “Do you not fear ridicule with this peace talk of yours?” “Oh yes, but what is ridiculous? I, having believed in a kind of ascending sunrise for the human race, or those whose convictions are being swallowed by the ascending darkness?”

Like Sørensen’s murals, Echoes is a beguiling and ambitious work, which aims, on a first level, to trace the re-emergence of Norwegian normality after WWII.”

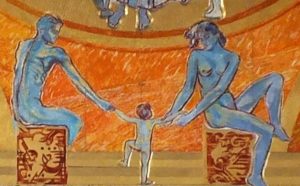

Like his League of Nations mural, Sørensen is still not a figure who might readily come to mind, especially outside Norway; yet he is a key element of Lars Saabye Christensen’s Echoes of the City, and at the heart of Oslo, whose tracks Christensen means to trace or even lay down. Another mural, very similar in its aesthetic idiom and intentions, was commissioned in 1937 and completed in 1950 in time for Oslo’s 900-year anniversary. It is another pyramid of history, a celebration of the everyday and the imperceptibly significant, an odd blend between Blake and Cézanne, Russian Formalist aesthetics and Viennese Secession principles, a paean to a city’s and a nation’s minutiae of greatness. It is a work of programmatic visuality, a pictorial ‘philosophic’ chronicle of life, rather than an erudite account of history; for Christensen, it is an ekphrastic device, a foil for his own Bildungs project which starts with Echoes and spans in its totality across three volumes. It confronts us with our own sense of importance, place in history and time, agency over public and private spaces.

Like Sørensen’s murals, Echoes is a beguiling and ambitious work, which aims, on a first level, to trace the re-emergence of Norwegian normality after WWII. Narrative sections, where architecture and history are juxtaposed with fragments of private stories, are intoned by the flatness and ostensible matter-of-factness of the minutes of local Red Cross meetings, creating a powerful point and counterpoint between the meticulously objective and the haphazard complexities of the emotive inner and outer life. Sørensen’s words on the seeming ridicule of optimism, or of a faith in humanity, echo throughout, as does a sense of the heavy weightiness, or at times dizzying weightlessness, of the past, of trauma, devastation, history, and our response to them. Christensen traces a fine line between realism and delusion, memory and forgetting, perseverance and fatality. He places his story sufficiently close to the end of the war, to the liberation of Norway from German occupation, for the sense of drama and tragedy to be strong and clear, and yet critically distant enough for there to be a powerful ambiguity between reconstruction and mere sequence.

Christensen constructs an intricate plexus of relationships and disconnected lives with the same attention to structural principles and the requirements of symmetry and static equilibrium as those of the architectural motifs that also run in parallel through his plot and his city. Family dynamics and wastelands are at the centre of his focus, as is the tension between action and paralysis, home and exile, loneliness and the crowding advance of a peace that outpaces itself. He shifts points of perspective continuously, with a particular sensitivity for narrative phrasing, for emulating stream-of-consciousness techniques without florid excesses or artifices, composing throughout a panorama of human imprints that capture the indelible permanence of ghosts and the ephemerality of the living.

In using broad brushstrokes of darkness or impending crisis, Christensen avoids clichés such as the conceit of a poetics of the dysfunctional, which entails a stagnating glorification of a self-destructive humanity. He paints instead a very human picture of a nation, of a community and individuals trying to redress a badly shaken world – or simply go on living. His is a rehabilitation process, a process of historical and personal reassessment of a very different kind, one that results in cinematic plot structures imbued with ironic humour and lyrical realism, noir undertones and a meticulous evocation of milieus, eras, period details, private and public moments in time. He possesses a powerful authorial voice that knows, nonetheless, to allow for a bold freedom in character development, for the ineffable malleability and intuitive autonomy of textual formation that can give rise to engaging fiction. Echoes is full of characters ready to inhabit a reader’s imagination – cryptic artistic souls or woody bureaucrats, worn-out couples, lonely hearts and Baudelairean lost souls, enigmatic pragmatists and Ovid-quoting, philosophising Italian pianists, shady respectable older gentlemen and prematurely angry younger men, exasperated wives longing for a new, emancipated female space; it is especially full of children, quietly troubled or blaringly damaged, who see what the eye cannot perceive, and can hear what has not yet been uttered; situations that are densely captured but also provokingly open-ended. It has hints of things past or things to come, shattered dreams and forlorn hopes.

Christensen creates for Oslo a path through time and our consciousness that is embroidered with the voices that give it (or ought to give it) what he defines as its ‘age’; its reality and legitimacy of being.”

Echoes is quite decisively full of things and people Norwegian, at least as far as architecture, the arts, music and literature are concerned. It is, in a way, a Norwegian saga, an anti-epic epic of a country and its people. In line with the motto of the firm that employs one of the central characters, “tradition and modernity”, Christensen creates for Oslo a path through time and our consciousness that is embroidered with the voices that give it (or ought to give it) what he defines as its “age”; its reality and legitimacy of being. Some of the references are obvious signals to a place and memory as well as the signifiers of a psychological and cultural undertext, such as Munch, Ibsen or Edvard Grieg. Others disclose the pre-existing fabric of semantic relations that Christensen relies on and is inspired by, such as Sigrid Undset, the 1928 Nobel laureate in Literature, who also wrote about Oslo and its inhabitants, focusing on what is little rather than what is great, on the trivial sounds rather than the grand themes; as did Johan Falkberget, who wrote about the experience of miners; the novelist Kristian Elster; the children’s writer Mathias Skeibrok, or the illustrator Theodor Kittelsen. There is a subtle but central place for books, architecture, music and the creative life in Echoes, as there has been in Christensen’s own life, and a staple feature of his writing: his earlier novel Modelen (The Model) focuses on a painter confronting the fear of blindness; Jubel is about a young pianist, and the tension between pure art and entertainment. Christensen revisits, revises, rethinks the stuff and elements of his craft time and again, insisting on the originality that is to be found in habit, repetition, reverberation.

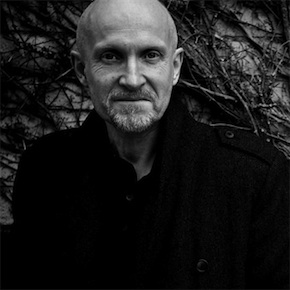

The son of an architect father, he studied literature and Norse languages, history of ideas and art history, and has offered the names of John Lennon, Knut Hamsun, Proust, Graham Greene, Hans Christian Andersen and Joseph Conrad, Tom Waits and the lesser known Sigbjørn Obstfelder, a friend of Munch and the subject of one of his lithographic portraits, as some of the voices that resonate through his writing. It is an almost cheekily eclectic mix, and one suspects there is also Joyce, Baudelaire, Strindberg, a multitude of others whose company Christensen is glad to keep. In a 2011 interview with Haaretz, he said that he “grew up in a home full of books. From a young age, I was drawn to myths, short stories, fables. They did not make me a writer, but rather a reader.” And it is his skill as a reader (and re-reader) of human psychology, historical nuances and the underlying causes of events that emerges most powerfully through his work. Because he ‘listens’ to the inherent narratives in books and in the lives around him, Christensen’s own murals of life or cities seek to align themselves with paradigms of greater interiority than Sørensen’s perhaps.

The Oslo City Hall painting elicits a reaction in the novel that is surfeit with layers of interpretation, as well as being a purported declarative statement of new values, directions, strengths of human endurance: to the shock of conventional society, it is not approved, for it is “four-sided and lifeless. It is magnificent and boring.” The everyday is made to “wear halos… It is a school book, a Bible, of 300 square metres.” This challenge is launched following a paragraph of astounding approbation: “In its centre is the child, who stands for hope and the future, but first and foremost woman, who is the form and essence of love. It can’t be simpler. And it can hardly be more beautiful.” All the elements enumerated here are also Christensen’s own, in Echoes as well as across the body of his work. So what is the meaning of the professed cynicism or contradiction? One of the answers, implicit, is that there are some moments in time when history and life seem to stop, because they are forced to be suspended in mid-action, or because they are permanently severed from the flux of time and eternity. This is the space of cynicism, of reactionism, negation. The litmus test between pause and terminality is ultimately our own humanity, the minutiae of our relationships, tragedies, joys, handicaps and imperfections, our banal everydayness. To have the insight of affirmation, of continuity, perhaps of transcendence, requires a leap of faith beyond the observation that “most things are incomprehensible and the rest is downright unbelievable.” The explicit answer is that “the humdrum will lead us to happiness.” And that one should not “try to impress; [or] rush; [but] just try to move people.” Also that the real skill in life is to know “how to carry out repairs on people” and that “memory is sorrow; history is reconciliation.” Just like Sørensen’s mural, almost every act or word can move or bore in equal measure; it is often as easy to destroy as it is to build, as easy to choose the good as it is to do harm or mischief. Christensen lures us into deceptively simple settings and situations, uncomplicated human lives, to thread through reflections and discourses with vaster significance, and one can only wait for the translation of the next two volumes to appear to follow his lead to a cadenza or a dolce resolution of his saga of Norway and humanity – and perhaps to a few answers regarding some of the hints he has prolifically dropped so far along the way.

Lars Saabye Christensen has published a number of novels, poetry and short story collections, his breakthrough coming in 1984 with Beatles, still one of Norway’s bestselling books. He received the Nordic Council Literature Prize for The Half Brother in 2001. He has also received the Riverton Prize, the Critics’ Prize, the Brage Prize, the Norwegian Booksellers’ Prize, the Dobloug Prize and the Norwegian Reader’s Prize. Echoes of the City, translated by Don Bartlett, is published by MacLehose Press in hardback and eBook.

Lars Saabye Christensen has published a number of novels, poetry and short story collections, his breakthrough coming in 1984 with Beatles, still one of Norway’s bestselling books. He received the Nordic Council Literature Prize for The Half Brother in 2001. He has also received the Riverton Prize, the Critics’ Prize, the Brage Prize, the Norwegian Booksellers’ Prize, the Dobloug Prize and the Norwegian Reader’s Prize. Echoes of the City, translated by Don Bartlett, is published by MacLehose Press in hardback and eBook.

Read more

@maclehosepress

Author portrait © Magnus Stivi

Don Bartlett completed an MA in Literary Translation at the University of East Anglia in 2000 and has since worked with a wide variety of Danish and Norwegian authors, including Jo Nesbø and Karl Ove Knausgård.

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.