Dreamland

by Mika Provata-Carlone

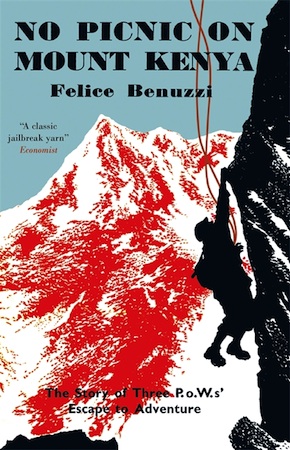

“The history of mountaineering can hardly present a parallel to this mad but thrilling escapade.” Saturday Review

No Picnic on Mount Kenya is neither a war memoir nor the travel log of an exotic mountaineering expedition; neither history pure and unimpeachable, nor a novel where the imagination is given free reign; it is neither biography nor documentary. It is, and explosively, all of the above – a grippingly beguiling tale as well as an unsettling testimony of the troubled, almost sinister relationship that post-Fascist Italy entertained towards the memory of its past. No Picnic on Mount Kenya is as much a startling, gorgeously written story, as it is an act of total erasure, a gesture of absolute control over words and their absence.

Felice Benuzzi’s book begins with a nightmarish ‘mirage’: a description that conjures up the most horrifying ghosts and blood-curdling images: PoWs arriving at a concentration camp in a long “cattle-truck ‘coach’”. This is the first shock that sends premonitions and adrenaline soaring, the first cold plunge into the enchantment and the darkness behind the blinding East African sun. In 1948, when the book was first published in Milan by the Eroica Press (which had aligned itself with the Futurists and Mussolini during the war), such a beginning could not fail to evoke battered Jewish prisoners in cattle-cars arriving at Dachau, Auschwitz or Treblinka from every patch of earth under Nazi (and Fascist) rule. Within sentences however, we have an anti-climax that causes double-vision: these PoWs have clout and whimsy, a sense of dignified resistance even in their abandonment to fate: “how long”, they wonder, do they have to stay there?

“Starkly, almost desperately it seemed, the gallows-like poles supporting the [barbed] wires reached towards the empty sky.” Yet there are rules to their doom, unlike Nazi camps – or Soviet camps, Italian camps in Africa or on Italian soil. In the first part of No Picnic, life and conditions in the British camp are given a tactile immediacy, a vibrant, elegiac eloquence: these are prisoners in the middle of vast grasslands, wastin’ time and staring at a mystical mountain – Mount Kenya.

The camp is a dehumanising prison, a place where life, individual and collective, loses coherence, meaning, direction, a before and after. Yet the suspension of existence, the assault against personal presence, suggests a superhuman challenge against an invincible element (an expedition to the Pole à la Shackleton) rather than a martyric struggle against human evil. Benuzzi quotes extensively from diaries of mountaineering and polar expeditions, and as an Alpinist, as the founder, later, of Mountain Wilderness and a pivotal actor in the efforts to ensure Italian presence in Antarctica, this would be a vernacular with particular appeal. “These truths [of psychological hardship] apply perfectly to our prisoner of war life.” Yet he will also quote from Admiral Cagni a different sentiment altogether: “I should like [Cagni says] to emulate a Spartan and lose all my bad habits. Never in my life shall I have a better opportunity for doing so.” Ascetic constraints, military discipline and privations provide a Nietzschean cliché: a ready, gutsy, witty response to a superhuman dare.

There is leisure and freedom to receive and open parcels and letters, there is time and the psychological space to go over possessions, to remember. “You just lie there and remember,” Benuzzi sighs, yet in Dachau, Auschwitz or Treblinka even forgetting (not just remembering) was verboten. There is time for nostalgia, rather than the vacuum of fear, a yearning to be able to choose what to forget, how not to remember. There is leisure and safety to wander around the camp, join conversations, observe, talk of the “small nothings” that in captivity are everything. There is time and space for that most Italian of things, il dolce far niente.

In Nanyuki, one yearns for ways to pass the time, and the British apparently spare no resources: we are told of drawing, reading, acting, boxing, crafts, cards or chess.”

There is a gentlemen’s club sense, an atmosphere of a jolly game of cowboys and Indians, where the losing side is tied to poles, waiting for another round of the game to begin, with slates clean for a fresh score. Time slows down in PoW camp 354 at Nanyuki, or even becomes enlarged, rather than being devoured or disappearing, as in other accounts of life or death in places of mass captivity. “Captivus vulgaris kenyensis is not a sub-species of Homo sapiens, but a superspecies. Here one finds concentrated humanity,” we are told: the prisoners are of a different race and kind from those penned up by the Italians in Abyssinia, Libya, Eritrea.

In Nanyuki, one yearns for ways to pass the time, and the British apparently spare no resources: we are told of drawing (charcoal or watercolours), reading (titles are on demand or on an ad hoc basis), acting, boxing, crafts, cards or chess, of leisure to set oneself tasks, however trivial and ridiculous. There are actors and entertainers, musicians, “their ability and ingenuity helped us to pass many delightful evenings.” There is certainly caustic irony in Benuzzi’s words, but also complacency, a sense that for some boring, tedious reason, one, one supposes, had to be there.

Forget the historic moment, the spectres of parallel narratives, the never referred to context of Africa Italiana and Italian war crimes, the fabricated image of Italy as a victim after WWII, and this becomes a deliciously captivating narrative of human endurance, of charm, noble resilience, mischief, humour and ingenuity in the face of adversity. It is an exquisitely told story of daring and adventure, a photographic image expertly cropped and magnified out of its historical frame. A vision of aniseikonia that leaves one reeling and mesmerised at the same time.

Our first view of Mount Kenya is pure poetry, with nothing to weigh it down, a genuine sublime experience: “and then I saw it. An ethereal mountain, emerging from a tossing sea of clouds… Austere, yet floating fairy-like on the near horizon… I stood gazing until the vision disappeared among the shifting clouds. For hours afterwards I remained spellbound. I had definitely fallen in love.” To consummate this love and to break the tedium, Benuzzi spins a Mad Hatter’s plan: break out of the camp with two accomplices, climb the mountain, and, like a new Phileas Fogg, walk back again and claim his bet: “Out marched the three prisoners” and in they marched again eighteen days later.

This is a rambunctious, beautifully written yarn, with old-fashioned lyricism and eloquence, a reverence for the right word and the lilt and elegance of phrases, the undulations of plot and the palette of characters.”

Along the way, we learn how they procure and make all they will need, we have cautionary tales of escaped prisoners walking round in circles, or stumbling into the arms of patrols, being run over by wild pigs and terrorised by African buffalo more formidable than lions; we are told about musical fences and traps for beasts as well as men, of miraculously avoided collisions with “quietly ruminating white cows”, of birds whose whistling is reminiscent of Radio Rome. Rations are prepared, calculated to 2,000 calories a man (!), to include chocolate, Ovaltine, Bovril, eggs that will acquire distinct vintage flavour, bread, barley sugar, plain and sweet biscuits and peanut butter, as well as the ubiquitous British corned beef… Also eight handkerchiefs and woollen socks, bought at the price of a copy of Shaw’s Pope Joan.

In its oblivion of history, this is a rambunctious, beautifully written yarn, with old-fashioned lyricism and eloquence, a reverence for the right word and the lilt and elegance of phrases, the undulations of plot and the palette of characters. It is as flippant, delightful and endearing, a true curio of the noblest vintage, as it is eerily unsettling in its total blinkering from any historical reality. “What fun it was to go through with the adventure in all its most childish details”, including a note to the Italian liaison officer in the camp: “we are leaving the camp and reckon to be back within fourteen days.”

There are exquisitely expressive surrealist descriptions, an irresistible seductiveness once one becomes absorbed in the allure of the mountain, wilderness, a spirit beyond the grasp of mere man. It is the ultimate escapist novel. The forest provides an imagery of idyll and nostalgia, medieval romance and a long lost world of human glory and grandeur: gothic cathedrals, mythic figures and old gold flicker in the shadows, orchestras and Greek amphitheatres conjure themselves up at every step and glimpse, “wrecks of ancient vessels”, perhaps the Flying Dutchman, have come here for eternal rest. On the roads, there are signs, “BEWARE THE RHINO”, and as for elephants, “no other creature, I thought, could represent in such a perfect way the strength, the dignity, the gravity and majesty of creation.” The adventurers are sometimes “as if blinded by an unnatural vision” and in our unmitigated enchantment, so are we.

Kenya has a mythic presence in the European imagination, from Karen Blixen to Lord Delamere, to the Happy Valley set: a place for socialites and fortune hunters, or free spirits seeking the space for their larger minds. Kenya’s flatlands and almost unknowable, terrible peaks feel like home to Benuzzi, a home of mental serenity away from threat, the awareness of human mortality and the troubled consciousness of Italian history. No Picnic on Mount Kenya is pervaded by an Alice in Wonderland feeling, it is a Brendon Chase for grown men written with childish gusto and naiveté, with a gallery of Edward Lear-like watercolours and sketches to illustrate the journey. Yet this is a grown man speaking and acting, an Italian centrally involved in the government of Abyssinia: a Governor of the Ministry of Italian Africa in 1938 and a General Governor of Italian East Africa in 1939 before his internment by the British. Someone who followed the orders of Rodolfo Graziani and Pietro Badoglio, who pledged, as he has said, allegiance to the Restored Republic of Salò after Italy ‘capitulated’ in 1943, for all that he was a royalist. Italy’s portion of WWII guilt and responsibility is still to be defined, whether in international or national memory and conscience.

If we read No Picnic on Mount Kenya with one eye closed, the eye of conscience, we are transported to worlds of mystery and wisdom that no longer exist. We can no longer write like this (and this is said with genuine regret), our stories are too concentric, too absorbed in a certain narcissistic jouissance. Benuzzi writes unselfconsciously, seduced by voices that speak of other realities and human potential. He possesses a linguistic sensitivity and richness that are intoxicating, soothing, reassuring. Mount Kenya inevitably becomes a symbol of obstacles surmounted, of eternity, of stability in a world that is collapsing, of a spiritual and mental ascent in the midst of a spiritual vacuum and intellectual mire. Magic, divine mountains like Mount Kenya perhaps exist only in myths and as myths, outside history, reality, mortality. Perhaps they exist only in dreams or only in vitally lived parables. If “one could spin a yarn,” Benuzzi says towards the end, to contain the transcendent, the beyond the human… Such yarns do not, cannot exist, he says, but if they did, perhaps this would be one of them, in a different space and time.

Felice Benuzzi was born in Vienna in 1910 and grew up in Trieste, doing his early mountaineering in the Julian Alps. He studied law at Rome University and represented Italy as an international swimmer in 1933–35. He was captured by Allied Forces as Italian-occupied Abyssinia fell in 1941 and imprisoned in Kenya until he was repatriated in 1946. Following the conclusion of the war he worked as a diplomat, including with the United Nations, and completed the memoir he’d begun writing in the prison camp in both Italian and English. He died in Rome in 1988. No Picnic on Mount Kenya is now published in paperback and eBook by MacLehose Press. Read more.

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.