Have you ever met the Greeks? They bear the most vital, wondrous gifts…

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“A warm, appealing narrative of how it feels to be ‘thrust into a conversation’ with fellow students about life’s most ‘serious and unsettling questions.’” Wall Street Journal

Nearly two and a half thousand years ago, a very old man slept in a bare prison cell. He was not alone, however. An old friend was watching over him, reluctant to wake him up to the day that would mark the end of his life. It is a cameo of extraordinary tenderness and humanity, of the most piercing political criticism and analysis, as well as of infinite private and historical tragedy, which has (or should have) the power to still affect us deeply today. It should make us think and feel, choose, as he did, who we really want to (and should) be.

The old man had been sentenced to death by the city’s high court for introducing (so the accusers had resorted to claiming) new gods, and for corrupting the young; he had been condemned especially for manipulating, it was purported, the minds of the young and the old alike, those of women as well as men, the minds and opinions of Athenians and foreigners, friends and foes, the rich together with the poor, everyone in short. The truth was, as it very often is, much different. The old man – you may well have guessed by now that it is Socrates – was up against forces both beyond him and beneath him. He had dared to oppose, philosophically, ideologically, in his every breath and gesture in life, the new up-and-coming neoliberal radicals of his age, namely the Sophists. The Sophists were furious with Socrates; where they pushed for cleverly intricate edifices of ratiocination on the basis of anything goes, if it makes the argument a winning one (and gets one a plump, hefty fee into the bargain), Socrates insisted instead, most uncooperatively and stubbornly, on proper, old-fashioned, honest and modest reasoning and transparency. He somehow did not fall for the Sophists’ newfangled tools of rhetorical persuasion, or their novel concepts of how to erase the distinction between right and wrong, truth and falsehood. He admitted ignorance, where they claimed powerful ownership of their personal narrative of truth; he argued for virtue, ideas and goodness, where they sought and sold, rather lucratively, power, ideology and success. He stressed and practised the principle of community and society, where they glorified the concept of the individual, the me-minded self.

For Socrates, the solution to a world in crisis (and his world, coming after the ravages of a harrowing war between the Athenians and the Spartans, was certainly a world in dire crisis) is not total demolition and rejection, but rather the conscious and reflective undertaking of reconstruction. For Socrates (and for the Classical tradition he derived from, and came to quintessentially represent) this means looking at the past from the perspective not only of what was wrong in it, but especially from that of what was right and worth keeping. It implies a paideia of humanity and culture, and an understanding of life as a time of service – to something really worth living and dying for. It presupposes an entire tradition of self-examination and reflection driven by the momentum towards that key Socratic concept of the Good, even when one (or the social whole) may fall well short of even its most basic preconditions; it requires a commitment to dialectics, and a conviction that humanity, its past and future, somehow matter. Socrates’ legacy of how to build a life and a society, how to respond to the crisis or even to the failure of our humanity, consists in a constant, active process of knowing oneself – for without that self-knowledge and self-examination, without the constant growth on the basis of such dynamic reassessment, both individuals and societies are left faceless and numb, brutalised and blank, emptied, annihilated. Today one might use the phrase that they become quite simply cancelled and erased.

Socrates’ acceptance of death would engage the minds and souls of generations in the centuries to come; it would become a topos for non-violent, yet powerful resistance to ideological totalitarianism, a lesson in humanity, in the value of a single life when it is truly lived well.”

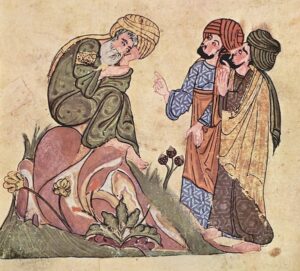

Socrates and two disciples from an illuminated manuscript of Mukhtar al-ḥikam by Al-Mubaššir ibn Fatik, which depicts the Greeks interestingly embedded within the Islamic tradition of representation. Topkapi Palace Museum, Istanbul/Wikimedia Commons

The condemnation of Socrates was, on the face of it, a victory for the Sophists and what they stood for: an emphasis on individualism rather than the Polis, and a focus on self-interest rather than on the Good or on public duty. It heralded a time when the advocacy for unchecked licentiousness, rather than for an ethics of freedom based on responsibility and relationality, sought to reign supreme; a new era of history when the prioritisation of ideology-driven and battle-ready structures of argument aimed to blur both substance and truth, and to cancel thoughtful intellection that sought to serve society and the principles of humanity it depends on.

Yet Socrates would emerge as the more enduring paradigm: his acceptance of death would engage the minds and souls of generations in the centuries to come; it would become a topos for non-violent, yet powerful resistance to ideological totalitarianism, a lesson in humanity, in the value of a single (rather than an individualistic) life when it is truly lived well. His determination to mark that moment of death by a gesture of gratitude to a god for having helped him to realise that life’s meaning, both lived and transcendental, would become an enigma as well as an oracle of hope for Socrates’ students, for anyone who, thanks to Plato, would choose to become Socrates’ diachronic intellectual companion, his fellow city-peregrinator and mind-and-soul pilgrim.

Roosevelt Montás is one of the most recent such intellectual companions to Socrates, to the Western tradition that has claimed that old man from Athens at its centre. And in his latest book, Rescuing Socrates, he pays vocal tribute to that companionship, as well as to the genealogy of intellectual becoming and dialecticity that it so vitally signifies. Montás seeks to rescue Socrates from the clutches and bigotry of ideologues, the extremist distortions of fanatical revisionists, the ultimately nihilistic utilitarianism of new(ish) trends in education (and in society’s self-definition) that seek to undermine the value and role of the humanities both in academia and in everyday life under the pretext of what they claim to be social egalitarianism, anti-elitism, inclusionism, and a nebulously globalistic multiculturalism.

Do absolutely read this book. At its heart is a very personal take on the Western canon and civilisation, which Montás values beyond all else, and which he urges institutions (and each of us) to enrich and open up to the dialectics it has fostered (and, most importantly, has crucially provided the basis for), rather than overthrow, destroy or reject it. Key to this perception is Montás’ extraordinary and inspiringly ordinary story, which he uses to challenge the very principles and motives behind the current impetus towards a virulent vilification of liberal education, the drive to cancel the Classics, the campaign to dismiss the entire European tradition of humanistic culture and reflection. Montás came to the US from the Dominican Republic as a migrant, experienced hardship and marginalisation, alienation and self-doubt. Yet unlike others with whom he shares the over-signalised bullet-points of an Othered bios, he rejects both the categories and the stereotypes, the determinism and the totalitarianism of a non-differentiated sociohistorical experience. Contra someone such as Dan-el Padilla Peralta, with whom he could be (disingenuously) compared, and who is spearheading a vehement onslaught on what he claims to be the colonialist, hegemonic and patriarchal systemic injustice of the Classical tradition and its European (and not only) Nachleben, Montás invites us to actually study both the Ancient and the later European past and identity. He urges us to look at what it truly is, what it can still offer us, rather than be hoodwinked by falsifying imageries and skewed image-making.

Do absolutely read this book. At its heart is a very personal take on the Western canon and civilisation, which Montás values beyond all else, and which he urges institutions (and each of us) to enrich and open up to the dialectics it has fostered.”

Young girl reading. 1st-century Roman bronze statuette after a Hellenistic model. Cabinet des Médailles, Paris/Wikimedia Commons

If Padilla Peralta is driven by what he defines as righteous anger and hostility towards the European tradition and the Classics for having, as he has claimed, excluded him, Montás is inspired by that same tradition’s gesture of inclusion towards him and everyone seeking to engage in the very project and experience of humanity. He tells us how he grew up in a small village, and in a house where ideas and principles mattered far more than material comfort; how from his father he learned the value of principles, freedom and human dignity, as well as the gentleness of human fallibility; how his mother supplied him with an inexhaustible sense of belonging and acceptance. He invokes the brothers, uncles, compatriots, neighbours, especially the teachers who marked him and guided him along the way. He conjures up the migrant journey to New York with comedy and tragedy, lightness as well as stark darkness, in ways reminiscent of the personal accounts of European immigrants to the New World since the 19th century – Italians and Russian Jews, Poles, Greeks and Irishmen, who would make tales out of their mere stories in order to remind themselves and those who listened to them “what living is for”, the indispensable question that according to Montás only a liberal education and a European tradition in a new dialectical engagement with other voices, historical experiences and storylines can seek to answer.

Rescuing Socrates is about personal journeys and rites of passage, as well as about the very purpose of education, the orientation and foundations of our society. Montás stresses choices over circumstances throughout, and this will ruffle a radical feather or two. Somehow for him goodness, the ability to think and reflect, and that old-fashioned concept of virtue do not have anything to do with socioeconomic conditions, even though economic conditions have very much to do with one’s potential to actualise that goodness, thoughtfulness and virtue for the greater communal benefit. Yet the choice to touch one single other person, the decision to do good rather than harm on an individual basis, to stop and think what one’s life should aim towards, is at the heart of what Montás defines as freedom – philosophical, sociohistorical, educational. It is what distinguishes the four authors he chooses in order to “bring the reader closer to the experience of liberal education”, to the essence of the tradition of reflection, critical understanding, and sociohistorical belonging that he feels is vital for the very survival of our human society: his four human and intellectual landmarks are Saint Augustin, Plato, Sigmund Freud and Mahatma Gandhi. Again, the chosen figureheads will make not a few hairs bristle.

Montás first came across Socrates (and Plato) quite physically: he found a discarded volume of Plato’s writings on a rubbish heap. Having rescued the rather beautifully bound edition that had belonged to the venerable Great Books of the Western World collection from certain pulping, Socrates and his pupil Plato rescue Montás in turn from an unexamined life. John Philippides, the son of Greek immigrants and Princeton graduate who had turned to teaching following a career in real estate, a priest who placed understanding above doctrinal propriety, and a series of enlightened teacher-scholars at Columbia who initiated him to the wonders of the Core Curriculum and to the paideia of the European mind were Montás’ gleefully, gratefully and exuberantly acknowledged intellectual guides and mentors. They were also the gadflies that urged him to follow them into teaching, and Rescuing Socrates is in many ways a private and intimate tutorial on what has been no less than an enchanted, as well as particularly clear-eyed engagement with the tradition and the practice of critical understanding, with the project of a culture of education, the praxis of a life of the mind that never forgets the actual living of life.

Just as it is poly-prismatic in terms of the voices it will bring into conversation, Rescuing Socrates is also polymorphous and stereophonic in terms of the levels of reflection it invites its readers to engage with. From the personal, Montás shifts seamlessly towards the political, the philosophical and the ethical, from the private he opens up to the institutional and the societal. At the heart of his analysis is John Erskine’s famous “moral obligation to be intelligent” – another likely trigger-concept for today’s vociferous brigade of aspiring Gorgias-apers. Montás laments the drive to purge and erase, and makes a formidable case for the inherent nihilism and auto-destructive impetus behind the attack against canonical culture and curricula. He shows how rather than address and redress questions of inequality, privilegism or cultural hegemony, such attacks deny an entire generation of critical understanding, of the ability to engage dialectically with themselves and other cultures, to acknowledge and seek to know the other altogether. In this systemic new iconoclasm against anything that is recognisable as a distinct, older and formalised historical and cultural framework (this would include the civilisations of China, India, Persia etc., as well as the multiple more strictly Western traditions), which favours a generic and undifferentiated (de-selfed) global subaltern, one can hear echoes of Suzanne Marchand’s incisive reading of Germany’s fascination with Orientalistik not too long ago: in her analysis, the determination to discredit antiquity in favour of ur-ancestries, non-derivative genealogies, prehistoric narratives and ethnographical rather than historic approaches was at the heart of nationalist/volkisch currents in late 19th-century Germany – currents which ultimately fed into the less folkloric and more nightmarish vision of the Volk of the Third Reich.

For Gruen, as for Montás, the past should be allowed to tell its own story, a story which might often irk the ideologists.”

One might want to perhaps take a step back, Montás argues, from the heated (rather than enlightened) debates on the Classics and Western civilisation which dominate both academia and popular anxieties today, in order to have the clarity to see (and to foresee, perhaps) comparable motivations behind many of these renewed, more contemporary attacks against a “non-decolonialised” curriculum or discourse. In this he joins company with another migrant scholar, the Jewish Erich Gruen who fled Vienna for America in 1939, and for whom the Classics and Western culture became the gateway for encounters, for the recovery of identity, history, human dignity and integrity, for connections and dialectical engagement. In Rethinking the Other in Antiquity Gruen argues against Edward Said’s concept of Orientalism (which stands disingenuously taciturn as regards non-Western hegemonies and colonialism, and what has now been given the name Occidentalism), Edith Hall’s presumed Greek-manufactured barbarians, or Benjamin Isaac’s elaborate arabesques in The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity. Gruen echoes many of Montás’ concerns, reflections and convictions, and his own lodestar is Arnaldo Momigliano’s Alien Wisdom: The Limits of Hellenisation, which he aims to complete, expand and problematise towards a broader discussion on the value of the past itself, the meaning of culture and tradition, the notion of belonging to space, time, history and humanity. The “Greeks, Romans, and Jews (who provide us with almost all the relevant extant texts [before a certain moment in time]) had far more mixed, nuanced, and complex opinions about other peoples,” he argues, as does Montás. And as he reminds us, “it is easy enough to gather individual derogatory remarks (often out of context), piecemeal comments, and particular observations that suggest bias or antipathy. The ancients were certainly not above prejudicial reflections on persons unlike themselves. It is a very different matter, however, to tar them with a blanket characterization of xenophobia and ethnocentrism, let alone racism.”

One might want to perhaps take a step back, Montás argues, from the heated (rather than enlightened) debates on the Classics and Western civilisation which dominate both academia and popular anxieties today, in order to have the clarity to see (and to foresee, perhaps) comparable motivations behind many of these renewed, more contemporary attacks against a “non-decolonialised” curriculum or discourse. In this he joins company with another migrant scholar, the Jewish Erich Gruen who fled Vienna for America in 1939, and for whom the Classics and Western culture became the gateway for encounters, for the recovery of identity, history, human dignity and integrity, for connections and dialectical engagement. In Rethinking the Other in Antiquity Gruen argues against Edward Said’s concept of Orientalism (which stands disingenuously taciturn as regards non-Western hegemonies and colonialism, and what has now been given the name Occidentalism), Edith Hall’s presumed Greek-manufactured barbarians, or Benjamin Isaac’s elaborate arabesques in The Invention of Racism in Classical Antiquity. Gruen echoes many of Montás’ concerns, reflections and convictions, and his own lodestar is Arnaldo Momigliano’s Alien Wisdom: The Limits of Hellenisation, which he aims to complete, expand and problematise towards a broader discussion on the value of the past itself, the meaning of culture and tradition, the notion of belonging to space, time, history and humanity. The “Greeks, Romans, and Jews (who provide us with almost all the relevant extant texts [before a certain moment in time]) had far more mixed, nuanced, and complex opinions about other peoples,” he argues, as does Montás. And as he reminds us, “it is easy enough to gather individual derogatory remarks (often out of context), piecemeal comments, and particular observations that suggest bias or antipathy. The ancients were certainly not above prejudicial reflections on persons unlike themselves. It is a very different matter, however, to tar them with a blanket characterization of xenophobia and ethnocentrism, let alone racism.”

For Gruen, as for Montás, the past should be allowed to tell its own story, a story which might often irk the ideologists, as is the case with “the prevailing scholarly consensus on the Greek image of Persia, the cornerstone of whose argument traces antipathy and Otherness to the aftermath of the Persian wars. Examination of Aeschylus’ poignant Persae, Herodotus’ intricate portrait of Persian practices and personalities, Xenophon’s fictive homage to Cyrus in the Cyropaedia, and Alexander’s remarkable receptivity to collaboration with Iranians presents [however] an important corrective.” One could add the sharp political self-critique in Trojan Women and Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War, and Homer’s narrative treatment of both Greeks and Trojans in the Iliad. Gruen also responds to the wholesale accusations of racism and Othering, to the “widespread idea that framing the self requires postulating the ‘Other’… Greeks, Romans, and Jews took strong pride in their own cultures, could disparage the different and abuse the alien, and periodically found reason to accentuate distinctions between themselves and the ‘Other’. But an alternative strand exists in the ancient mentality, a significant and telling element too often overlooked and requiring emphasis. The establishment of a collective identity is an evolving process, intricate and meandering. To stress the stigmatization of the ‘Other’ as a strategy of self-assertion and superiority dwells unduly on the negative, a reductive and misleading analysis. The lens here is turned on inclusion rather than exclusion.”

In Rescuing Socrates Montás invites readers into a vital conversation, into sharing a conversation, in fact, that has been going on for the best part of 3,000 years.”

For Montás too, vitally, radically and unyieldingly, “the lens is… turned on inclusion rather than exclusion”, and the critical value of the Classics, the tradition of Classical cultures East or West, and the liberal arts curriculum (or the study of the Greats) consists not only in what it can give us, in the paideia of understanding that it has engendered, but also in the praxis of dialectical engagement and wonder that it postulates as an axiomatic prerequisite for any encounter, whether with the past or with the present and future. As Montás writes, focusing particularly on current urgent questions of access, diversity and inclusivity, “we do minority students an unconscionable disservice when we steer them away from the traditional liberal arts curriculum… We condescend to them when we assume that only works in which they find their ethnic or cultural identities affirmed can really illuminate their human experience.” Moreover, and audaciously, he argues that “the demographic diversity of the student body… necessarily leads to incoherence, essentialism, and tokenism.” In other words, we create yet another hegemony, yet more structures of blindness and intolerance, of an entitlement to ignorance, indifference and the erasure of another. Or, as he again stresses: “a liberal education [rooted in the Western tradition] is one that takes the complicated condition of human freedom seriously and addresses itself to its dilemmas and to the urgency of its lived experience” – just as Socrates made philosophy into a lived experience in the streets of Athens.

“To think and reason through these kinds of questions” in the company of all those who have thought and reasoned about them before us “is to learn to live with them in an honest and ongoing way.” On the contrary, and to Montás this is perhaps the other principal, toxic element in most social and cultural-pedagogical discourses today, to reduce both the concept of a canonical tradition of culture and education, as well as the liberal arts curriculum to so-called structures of “oppression and subjugation [evades] the actual question of the human good by saying that, in effect, the question cannot be asked.” Worse still, the engineered answer behind such rhetorical sleights of hand is “the ultimate emptiness of any notion of the human good.” In Rescuing Socrates Montás aims to rescue the notion of both the human good and the tradition that has taught us to seek it, to examine its premises and purpose, to attempt to build a tradition around it by embedding it in every gesture and manifestation of our society and individual lives. He invites readers into a vital conversation, into sharing a conversation, in fact, that has been going on for the best part of 3,000 years. His wish is that it may continue, with new interlocutors ever joining the older ones, rather than displacing them, and throwing them out of their nests cuckoo-like.

Roosevelt Montás is Senior Lecturer in American Studies and English at Columbia University and the former director of Columbia’s Center for the Core Curriculum (2008–18). He was born in the Dominican Republic and moved to New York as a teenager. In 2003, he completed a PhD in English, also at Columbia; his dissertation, Rethinking America, won the University’s Bancroft Award. He regularly teaches moral and political philosophy in the Columbia Core Curriculum as well as seminars in American Studies. He is also director of the Center for American Studies’ Freedom and Citizenship Program, which brings low-income high school students to the Columbia campus to study political theory and then helps them prepare successful applications to college. Rescuing Socrates is published in hardback, eBook and audio download by Princeton University Press.

Roosevelt Montás is Senior Lecturer in American Studies and English at Columbia University and the former director of Columbia’s Center for the Core Curriculum (2008–18). He was born in the Dominican Republic and moved to New York as a teenager. In 2003, he completed a PhD in English, also at Columbia; his dissertation, Rethinking America, won the University’s Bancroft Award. He regularly teaches moral and political philosophy in the Columbia Core Curriculum as well as seminars in American Studies. He is also director of the Center for American Studies’ Freedom and Citizenship Program, which brings low-income high school students to the Columbia campus to study political theory and then helps them prepare successful applications to college. Rescuing Socrates is published in hardback, eBook and audio download by Princeton University Press.

Read more

@rooseveltmontas

@PrincetonUPress

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

bookanista.com/author/mika/