Fast Fashion in the age of the Sun King

by Celia Bell

Open up Tiktok – or Instagram, if you prefer. Depending on your viewing habits, you might see mostly influencers unboxing bales of new clothing from Shein and other fast-fashion retailers, or laughing over cheap knockoffs that don’t live up to the photos online, or styling their wardrobe of vintage pieces from the Victorian era up through the ’90s. But whether they’re showing off trend pieces meant to be worn only a few times before they go out of style or fall part, or second-hand clothing lovingly preserved through the years, what stands out is the sheer volume of possible outfits. And in response, if you’re interested in sustainability, or workers’ rights, or handcraft, you might hear a common critical refrain: people in the past simply didn’t own this many clothes.

While globalism has without a doubt sped up the process of conspicuous consumption, the competitive itch to own a lot of clothes – preferably new, on trend, and expensive-looking even if they’re cheaply made – is not an invention of the 21st century. Reading today’s fast-fashion debates, I’m often reminded of the fashion world of ancien régime France – and the way that the accelerating clothing consumption of that era became a flashpoint for debates about the role of women in society. History is often cyclical: while our conversations about clothing, style and gender are intensified by the conditions of modern globalism, they have old and deep roots.

Until the late 17th century, the mainstay of an aristocratic French woman’s wardrobe was the formal dress, which had a long, rigidly-boned bodice and metres of elaborate skirts. Requiring many hours of skilled labour and nearly as many yards of expensive fabric to make, they were accessible only to the very rich, and even noblewomen generally only owned very few of them. In the latter half of the 17th century, however, the formal gown began to replaced for daily wear by the mantua, a casual dress modelled after a dressing gown, and later by the floating robe volante, a loose dress worn over an elaborate hoop skirt. Because these dresses didn’t have the built-in boning of a formal gown, they didn’t have to be fitted as precisely, and required both less fabric and less labour – and that meant that fashionable outfits were suddenly much more affordable.

Suddenly, wealthy women were expected to have a much greater variety of outfits, and to replace them more frequently. Clothing no longer simply communicated the wearer’s social class – it was daring, sexy, experimental, or silly and passé. Most of all, however, it was a skill that rich women were expected to learn. Periodicals began to report on what was in fashion and what wasn’t. One winter it might be a flame-coloured muff and a brocade skirt with silver accents, as reported in the Mercure galante of 1678, but by spring the brocade was out of fashion, replaced by gauze and English lace. Women far outside of Paris waited for the style dispatches from the city, which arrived in the form of fashion plates in newspapers and elaborately-dressed dolls sporting miniature versions of the latest styles.

The ‘precieuses ridicules’ of Molière’s play – provincial women aiming to imitate Parisian fashions in dress and in etiquette – were laughed at in both Paris and the provinces for their foolishness and frivolity.”

These new fashions became an enduring part of debates about the role of women in the cultural and political life of France. In the middle of the 17th century, Molière would find success with the evergreen topic of “women who are shallow and think much too highly of themselves” in Les precieuses ridicules. The precieuses ridicules of Molière’s play – provincial women aiming to imitate Parisian fashions in dress and in etiquette – were laughed at in both Paris and the provinces for their foolishness and frivolity, but the true humiliation of Molière’s heroines occurs when the two friends fall in love with a pair of dashing (and well-dressed) valets, rather than the well-born gentlemen their families prefer.

Presented as an indictment of the ladies’ focus on appearances over substance, the play skates over a deeper insecurity about love and class: if women are given free rein to set the fashions in clothing and in discourse, what guarantee is there that they will continue to uphold the old power structures when it comes to who they love and who they marry? What if those rich and fashionable ladies weren’t embarrassed to prefer a handsome and charming servant over the men their fathers might have picked for them? Of course, the play does not end that way: the silly girls are united, at long last, with lovers of the correct social class. But what if?

Molière was not the only one to take issue with the new fashions. Conservative writers of all stripes would take aim at the waste and frivolity of the new styles – and the sexual freedom they implied. Dresses that bared ladies’ arms and throats came under particular fire – as did cross-dressing, which became a reactionary metaphor for all forms of women’s cultural participation. In 1638, Guez de Balzac, one of the founding members of the Academie française, would write that women who write books “use their minds to cross-dress” (translation courtesy of Tender Geographies, Joan DeJean’s wonderful history of the early French novel).

The life of clothes, however, is contained not just in what they mean to those who wear them, but also in the manner of their making, and in what happens to them after they are discarded. While we often think of textile work as traditionally female labour, the French world of clothes had a strictly enforced gender hierarchy, and until the late 17th century most prominent tailors were men. The articles of clothing that female seamstresses were allowed to make were governed by guild statutes, which forbade them from making formal dresses, traditionally the most expensive and difficult garment to make – and therefore the most prestigious and lucrative to sell.

Some women, of course, ducked the guild statutes and made formal dresses in secret, but with the advent of the new, less formal styles, seamstresses began to be able to market their most fashionable work openly. These seamstresses often used their own clothing to advertise their skill, making stylish outfits out of cheap cloth to show what they could with even the simplest fabric. For this reason, they began to be commonly called grisettes, after a particular inexpensive style of grey fabric they often used.

For a brief season, clothes made from seamstress’s cheap grisette even became fashionable for the rich, lending the aristocratic women who wore them an aura of illicit sexuality.”

While the expanding clothing trade offered employment to more and more women over the course of the 17th and 18th centuries, the working conditions were often bad. Nicolas Restif de la Bretonne, an 18th-century romance writer who holds the dubious honour of having contributed his name to the technical term for shoe fetishism (retifism, dear reader!), excoriated the cruelty of wealthy women who obsessively haggled over their seamstresses’ prices, a practice which he claimed drove wages for assistants down to an unliveable 10 or 12 sous a day. Many of these wealthy women were themselves buying on credit, and might take years to pay off their bills – if they paid at all.

Restif’s interest in the plight of the destitute seamstress has a somewhat voyeuristic quality, but contemporary records show that seamstresses – especially assistants and apprentices – often put up with sexual harassment as a condition of their work, and some complained that their employers expected them to engage in sex work on the side. For many male observers, on the other hand, the economic precarity of female garment workers made the seamstress a seductive figure. For a brief season, clothes made from seamstress’s cheap grisette even became fashionable for the rich, lending the aristocratic women who wore them an aura of illicit sexuality.

Over time, it became more difficult to distinguish a person’s class by her clothing. Middle- and working-class women began to buy and wear their own mantuas cut from inexpensive fabric. A lively market for second-hand clothes also sprang up, and many women (and men) bought hand-me-down versions of expensive clothes that were no longer quite in fashion.

On the eve of the French Revolution, a century after these changes began, Louis-Sébastian Mercier would describe these second-hand clothing markets in his Tableau de Paris: “a whole province might have been unfrocked to clothe its stalls, or a whole people of Amazons despoiled… [The shoppers] all change in public, but so far only the upper garments; no doubt it will get down to petticoats soon. The buyer neither knows not cares whence come the corsets she sells; a poor honest girl will clasp about her, under her mother’s very eye, some garment that a kept dancer of the Opera has discarded only the night before. Virtue, or rather vice, goes out of them when they change hands.” He goes on to add that “a woman pricing and coveting clothes has an unmistakable expression; the term ‘fair sex’ at such moments is a misnomer.”

I believe that we can safely assume that Mercier would not have liked Tiktok. But even to his critical eye, there is an unnerving alchemical transformation happening in that second-hand clothing stall, where the women strip down in public to try on clothes. How many hours of someone’s life are bound up in that corset? What memory – if any – does it hold of the woman who made it, the woman who wore it for her lover or her patron, and the one who salvaged it after it was discard?

Note: this essay relies on research from a number of sources. In particular, casual readers might enjoy Joan DeJean’s The Essence of Style, while Clare Haru Crowston’s Fabricating Women is an essential academic text about the changing 17th-century Parisian fashion industry for anyone interested in fashion and its social implications.

—

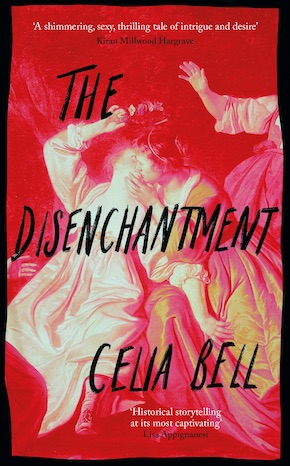

Celia Bell’s short fiction has appeared in VQR, The White Review, The Sewanee Review, The Southern Review and elsewhere. She holds an MFA from the New Writers Project at the University of Texas and lives in Austin, where she works in beekeeping when not writing. Her debut novel, The Disenchantment, about two women in 17th-century Paris drawn into the volatile and mysterious Affair of the Poisons after a bid to keep their passionate romance a secret, is published by Serpent’s Tail.

Read more

@celiadbell

@serpentstail

Author photo by Jinni J