George Saunders: ‘My Flamboyant Grandson’

by Linda Mannheim Sometimes, when I’m walking down the street, I think about the grandfather in ‘My Flamboyant Grandson.’ George Saunders’ story is set in a semi-absurd dystopia where every citizen is required to wear Everly Strips on their shoes, bar-coded soles that summon customised ads to ubiquitous public screens, phantom voices beckoning to you as you amble towards your destination. “And then,” the grandfather tells us, “best of all, in the doorway of PLC Electronics, a life-size Gene Kelly hologram suddenly appeared, tap-dancing, saying, ‘Leonard, my data indicates you’re a bit of an old-timer like myself.’”

Sometimes, when I’m walking down the street, I think about the grandfather in ‘My Flamboyant Grandson.’ George Saunders’ story is set in a semi-absurd dystopia where every citizen is required to wear Everly Strips on their shoes, bar-coded soles that summon customised ads to ubiquitous public screens, phantom voices beckoning to you as you amble towards your destination. “And then,” the grandfather tells us, “best of all, in the doorway of PLC Electronics, a life-size Gene Kelly hologram suddenly appeared, tap-dancing, saying, ‘Leonard, my data indicates you’re a bit of an old-timer like myself.’”

The grandfather wants to show his young grandson Gene Kelly, but in a world where ads are tailored to every citizen’s ‘preferences’, this is impossible. An ad featuring Babar, urging the purchase of a Nintendo, is dazzling the grandson.

Saunders has said that his first two books “came out of a kind of shock at the realisation that life could be hard and capitalism could be harsh,” and ‘My Flamboyant Grandson’ is certainly one of these stories. An elderly man lives in a rundown town where he and his wife are raising their abandoned grandson, a boy so at odds with the provincialism of their community that he is met with an absurd level of hostility. After hearing that the boys, girls, teachers, bus drivers, and churchgoers all treat the grandson either brutally or indifferently, we are told that that the grandson was “once found walking home from school in tears, padlocked to his own bike!”

It is from this small-town conformity that the grandfather attempts a rescue, taking the grandson on a trip to New York to see his first Broadway musical, Babar Sings! The boy is happily obsessed with both Babar and musicals, singing the soundtrack day and night, appearing unannounced at a church dinner in “a tablecloth spray-painted grey, so as to more closely resemble Babar.”

But the trip can only be carried out by using a cost-cutting voucher, and the voucher can only be used when it’s submitted to the Redemption Centre with “Proof of Purchase from at least six of our Major Artistic sponsors, such as AOL, such as Coke…” And so the grandfather and his grandson begin the walk to the office where they can collect their “real actual tickets”, bombarded by ads and afraid to be late for the start of the play. And the grandfather, when his feet begin to blister and bleed, elects to walk the rest of the way barefoot. And once his Everly Strips are no longer striking the Everly Detectors, the ads stop appearing. He has broken the law.

‘My Flamboyant Grandson’ first appeared in The New Yorker on 28 January 2002 – five months after the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Centre. While – given the lag time between acceptance and publication – Saunders is likely to have written the story before the attack, the authoritarianism that became part of daily life in America during this time is deftly captured. A ‘Citizen Helper’ – really a sinister enforcement officer – admonishes the grandfather for taking off his shoes: “Please do not snap at me, sir. I hope you are aware that I can write you up.”

And write him up he does. A week later, the grandfather receives a certified letter commanding that he walk the same path he walked earlier, this time with his Everly Strips on so he can view the ads he missed earlier, or face a $1,000 fine.

Hilariously, as I was trying to view the digital version of the story on The New Yorker’s website, a pop-up ad floated into my line of vision and blocked access to both the story and Art Speigelman’s accompanying illustration. Archival images of the 1960s appeared instead of the material I was trying to access, and an announcement for CNN’s history series rolled on until I clicked the floating window closed. Now what made them think I was interested in seeing that?

Saunders’ story, of course, appeared before information about our interests were collected by our smartphones and browsers, before we began seeing Facebook ads for products we’d just been looking at in Amazon. And the story’s voice, its structure, harkens back to a time before that. The rambling old man with so much tenderness for his misfit grandson, making his way through the cartoonishly doctrinaire dystopia, sounds like a narrator from a Grace Paley story sometimes:

“This to me is not America. What America is to me is a guy doesn’t want to buy, you let him not buy, you respect his not buying… America to me should be shouting all the time, a bunch of shouting voices, most of them wrong, some of them nuts, but please, not just one droning glamorous reasonable voice.”

The grandfather, we’re told, is named Leonard Petrillo, was raised on a farm in Upstate New York, is a veteran of the Korean War. But none of that jibes with his style of narration, with his own anarchic and outraged voice. He sounds like a New Yorker in exile, rhythms rooting back to Yiddish that once infused the English of everyone in New York: “If he is a gay child, God bless him, if he is a non-gay child who simply very much enjoys wearing his grandmother’s wig while singing ‘Edelweiss’ to the dog, so be it…” In the end, the voice outshines the incidental facts of the grandfather’s past. I don’t buy for a minute that this is an Italian-American war veteran who grew up on a farm. And I don’t care. I love this old guy and the little boy he’s trying to raise.

Saunders’ stories – nearly all of them – are about people trying to make ends meet in harsh but ridiculous circumstances. Humiliated by bosses, brutalised by corporations, often at the mercy of friendly fascists, most of them do somehow move towards redemption instead of defeat. Usually this is because of some kindness shown to one character by another. And ‘My Flamboyant Grandson’ gives us exactly this. Though he has no illusions about the “incredulous snickering” townspeople they are forced to live with, the grandfather’s faith in his grandson ultimately shines. The boy “fits no mould and has no friends, but I believe in my heart that someday something beautiful may come from him.” And so do we in the end.

Linda Mannheim is the author of the novel Risk, written while she was a visiting associate at the University of Cape Town’s Centre for Africa Studies, and the story collection Above Sugar Hill, now published by Influx Press. Her stories have appeared in Nimrod International Journal, The Gettysburg Review, New York Stories, New Contrast and Bookanista. She lives in London. Follow her on Twitter: @LindaMannheim

Linda Mannheim is the author of the novel Risk, written while she was a visiting associate at the University of Cape Town’s Centre for Africa Studies, and the story collection Above Sugar Hill, now published by Influx Press. Her stories have appeared in Nimrod International Journal, The Gettysburg Review, New York Stories, New Contrast and Bookanista. She lives in London. Follow her on Twitter: @LindaMannheim

lindamannheim.com

Read the story ‘Business’ from Above Sugar Hill.

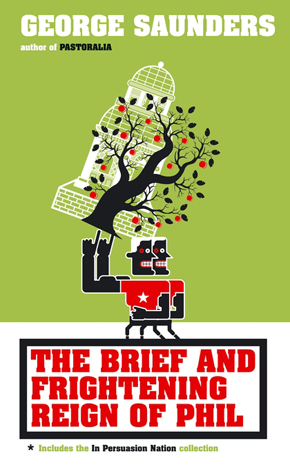

George Saunders’ latest story collection Tenth of December won 2014’s inaugural Folio Prize and is published by Bloomsbury. ‘My Flamboyant Grandson’ appears in the collection In Persuasion Nation (2006) and together with the novella The Brief and Frightening Reign of Phil (2007).

georgesaundersbooks.com