Flowers in a jam jar

by Mika Provata-CarloneIn April 1961 Ernest Hemingway would distil, in almost oracular terms, the nature of the writing act as a way of capturing the world, as a way of relating to life, but also as a way of confronting the inexorable absence at the heart of much of existence: “In writing, there are many secrets. Nothing is ever lost no matter how it seems at the time and what is left out will always show and make the strength of what is left in. Some say that in writing you can never possess anything until you have given it away or, if you are in a hurry, you may have to throw it away… You may not have it even until you state it in fiction and then you will have to throw it away or it will be stolen again.”

From Ovid to Blake, to Yeats and so many more, the words of poets and writers, once on the (un)published page, have met with varying fates; once read (or misread), they become fused with the voices, the thoughts, the flesh and breath of others, enriched or contaminated with multiple consciousnesses, and endowed with a power that defies their creators. To write is to a great extent to relinquish, to lose, even to allow oneself to be robbed naked of all that once formed both substance and spirit. From the very beginning, the anxiety of writing has also been the anxiety of erasure, the angst of authorial presence, the binary conflict between truth and fiction. With In Search of Lost Books: The Forgotten Stories of Eight Mythical Volumes, Giorgio van Straten adds to the list the trauma of annihilation – of manuscripts and lives.

In this slim volume, rather beautiful in its conflagrated, scarlet binding, van Straten treats us to a quiet firework display of vignettes on the theme of loss, suppression, destruction, forgetting, displacement, even murder. In Search of Lost Books is about the heartthrob at the centre of literary production, about the minutiae of greatness (and the darkness or desolation that lies within), about the failing humanity that so often produces the most astonishing monuments to its cruciality and urgency.

Lost books are those that are irretrievably and lamentably forsaken, the quest for whose absence would have entailed no lesser feat than Proust’s “amorous… risk of an impossibility” and “justified that combination of impulse and melancholy, of curiosity and fascination, which develops with the thought of something that existed once but that we can no longer hold in our hands.” They are that special category of books where it is “the void itself which fascinates us.”

In Search of Lost Books presents a private view of lost masterpieces, a particularly eloquent, lightly philosophical display of select, exceptional absences.”

Van Straten has always had a fascination and determined fondness for the state of lostness – not simply for loss, but for any form of being in absentia. In My Name, A Living Memory (2000; English translation, 2003), he embarked on a thinly disguised auto-fiction in search for the lost stories of his family, from main genealogical trunk to robust branches and delicate twigs and offshoots of connectedness, from the Napoleonic wars to WWII. He conjures lives on the basis of the most fragile evidence they left behind – waiflike traces of a presence that survived through a mighty challenge to impossibility, retaining indomitably their value of truth, against all odds. Reconstruction, even fictional, is the way to oppose and fend off lostness.

Van Straten is a rather exceptional guide, whose cultural presence is by no means ethereal. He has written novels, plays and librettos, translated classics from English into Italian and he has written widely as a critic, as well as curating Italian culture both at home and abroad. He has also been in charge of the Papal Stables at the Palazzo del Quirinale in Rome, but, as he wryly notes, only for its programme of exhibitions. His family includes a radical activist, a literary agent whose list of clients included Elias Canetti, Heinrich Mann and Joseph Roth, musicians, artists, businessmen and politicians. It is fair to say that he writes not only as a literary man, but as a host, a curator of words, history and stories, of literary lives. In Search of Lost Books presents a private view of lost masterpieces, a particularly eloquent, lightly philosophical display of select, exceptional absences.

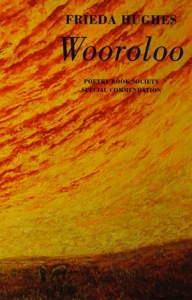

Eight works by as many authors make his list: we follow each time both writer and work as they proceed to disappear – through an act of self-destruction, loss, suppression, through enigma, suicide or murder. We learn of the activity behind publication or eradication, of the clashing tension that arises when art imitates life – or vice versa. The examples of Romano Bilenchi, Lord Byron and Sylvia Plath seek to interpret, find coherence in the destruction of manuscripts by others, left to decide the destiny of words after the voice of their writer was no longer there to speak another fate. Ernest Hemingway adds a whodunit note: a suitcase (the first of two to feature in this volume) mysteriously disappears – or perhaps is stolen or spirited away to erase traces of inadequacy. ‘Memory Is the Best Critic’, the title of that chapter, reverberates almost sardonically, evoking Hemingway’s mastery but also musty darkness. Bruno Schulz and Walter Benjamin are perhaps the paradigms van Straten feels are closer to the crux of his subject, his quest, and perhaps all literary absence. Here we have murder and regeneration, tragedy and lives seen through the prism of fate – ill fate – and of a particularly rare and beautiful human purity. Nikolai Gogol, Malcolm Lowry and Sylvia Plath (again) will wrap things up: the time-honoured star quality of the poète maudit(e) is the centre of scrutiny, as well as of awe and admiration. The self-destructiveness of absolutes and of perfectionism, the abusive allure and aura of the doomed artist, the layers of troubled humanity behind an expurgated literary idol are quietly yet powerfully laid out in front of us, with no eschewing of the tragic vision. Van Straten often hints through quotes at paths we as readers are meant to follow. Perhaps his most staggering nudge in this direction is from Frieda Hughes’ 1997 poem ‘Readers’, written about her mother, Sylvia Plath:

While their mothers lay in quiet graves

Squared out by those green cut pebbles

And flowers in a jam jar, they dug mine up.

Right down to the shells I scattered on her coffin.

They turned her over like meat on coals

To find the secrets of her withered thighs

And shrunken breasts.

They scooped out her eyes to see how she saw,

And bit away her tongue in tiny mouthfuls

To speak with her voice.

But each one tasted separate flesh,

Ate a different organ,

Touched other skin.

Insisted on being the one

Who knew best,

Who had the right recipe.

When she came out of the oven

They had gutted, peeled

And garnished her.

They called her theirs.

All this time I had thought

She belonged to me most.

It forces him to ponder that “however sensitively I have tried to proceed… perhaps I too have joined the hordes of cannibals” eating away at the flesh of a literary life.

Writers are not alone with their words – even when their words are alone without their creators. Friends – van Straten’s own, who provide support, information, inspiration, connections, versions of truth, fiction and sometimes fatality, but also the friends (or foes) of each of these eight authors – are central to this conversation on the theme of the presentness of absence. Van Straten is at his best when evoking figures like Gogol, Benjamin or Schulz. He seems particularly attuned to their almost blessed capital of tragedy and the horror of the catastrophic climax to what were truly inimitable, incomparable minds, talents, lives. In such instances, his shrewdness and poetic instincts serve him powerfully, lending his text impetus and a certain aura of enchantment. “Aura: a combination of distance, singularity and wonder that signalled the superiority of the artist in relation to the world.” Benjamin’s aura as a quintessential European and “consummately refined revolutionary.”

Throughout this chronicle of loss – even perdition – van Straten remains hopeful. “There is no absence, if there remains the memory of absence… If one no longer has land but has the memory of land, then one can make a map” are words by Anne Michaels that he quotes early along his quest. And he concludes with a promise of possible discovery, with a pledge of patience, and with the confirmation of faith: perhaps somewhere sometime something will emerge, in a literary archive or stash still to be explored. In the age of paper and pen such optimism spurred the efforts of many, thanks to whom stories and maps have been not infrequently retrieved. Even Aristotle’s lost book on Comedy may lie, still to be deciphered, in some long-frayed, forgotten palimpsest. As words are delegated to hard drives, one is tempted to ask whether another loss might be added to our lot – the loss of tactility, corporeality, the image of an individual hand tracing the course of an individual mind. Van Straten’s search for lost books is a rewardingly, reassuringly old-fashioned quest in so very many ways, it is even a quest for old-fashionedness itself.

Giorgio van Straten is an Italian writer and manager of arts organizations. He has written other five novels and a book of short stories, and in 2000 he won the Viareggio Award for Il mio nome a memoria, published in English as My Name, A Living Memory. He has served on the board of directors of the Biennale di Venezia and as president of AGIS, the Italian association for the performing arts. In 2015 he became the director of the Italian Cultural Institute of New York. In Search of Lost Books, translated by Simon Carnell & Erica Segre, is published by Pushkin Press.

Giorgio van Straten is an Italian writer and manager of arts organizations. He has written other five novels and a book of short stories, and in 2000 he won the Viareggio Award for Il mio nome a memoria, published in English as My Name, A Living Memory. He has served on the board of directors of the Biennale di Venezia and as president of AGIS, the Italian association for the performing arts. In 2015 he became the director of the Italian Cultural Institute of New York. In Search of Lost Books, translated by Simon Carnell & Erica Segre, is published by Pushkin Press.

Read more

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.