Giannis Paschos: Not necessarily in the right order

by Alexandra Samothraki

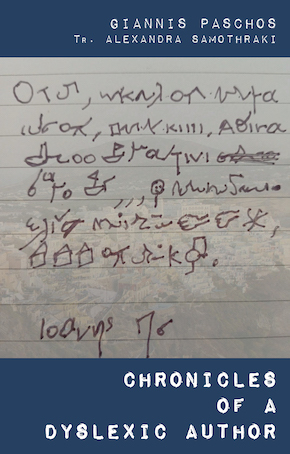

LITTLE COULD THIS dyslexic boy, growing up in a small mountainous village in Epirus in the 1960s, have known that he would go on to conquer the worlds of academia and literature, with his unruly imagination as his only weapon. When his memoir Chronicles of a Dyslexic Author was published in Greek in the summer of 2022 by Perispomeni Editions, I happened to be on holiday on the gorgeous island of Lefkada. There, by the turquoise waters of the Ionian Sea, I met Giannis Paschos to interview him about the book. My first thought was, is he – or any of this – for real?

Without being a professional translator, I decided then and there to translate the book into English, fully aware of my own limitations but feeling it unfair for the rest of the world to miss out on Giannis’s talent and unique perception of reality. My suspicion that this was a somewhat sacrilegious act – one demanding sacrifice – was confirmed when, since the English edition was published by Stairwell Books this month, I find myself speaking far more basic English. My verdict? Totally worth it!

Giannis and I recreate here our very first interview, slightly expanded after the success of the book, so you can see for yourselves.

Alexandra: You were such a poor student, yet somehow managed to turn things around and become a Professor of Ichthyology and one of the quirkiest voices in modern Greek fiction. I can’t help but ask: are words like fish in any way?

Giannis: Of course! Words swim around exactly like fish do. But if you manage to grab them, unlike fish that perish, words come alive.

Is it just the letters that are unruly on paper – or ideas too?

Ideas are as unruly as they come! They make you run after them, but when you finally catch them, they surrender and make it all worthwhile. Personally, I find that letters are crueller – almost despotic. They never give up and always somehow manage to escape. I’ve never discovered where they go.

You have a new collection of short stories about imaginary sea creatures coming out in Greek – first published in the literary magazine Hartis. Do you think fish also make up stories about humans? If yes, what would they say about the Paschohaddock?

I tell tales with tails – and without! It’s true, fish make up terrible stories about us. Take the indecisiveness of the swallowfish, for instance: not only does he not know whether he’s a fish or a bird, but he also reminds me of my own indecisiveness (should I have done this or not? should I stay or should I go?). Or the amazing metamorphoses of the cuttlefish when looking for a mate – they’re so much like human flirting. I’m not sure what the fish would say about the Paschohaddock. Perhaps they’d think of me as one of the subspecies of Acanthus Idiots, one of which I describe as “annoying, lonely, negative about everything – rude, arrogant, merciless, disgusting.”

Dyslexia forced me to be twice as alert – to observe everything. To remain on the bridge that connected the real, which tortured me, with the imaginary, which soothed me. It was a natural process.”

Let’s talk about your memoir, Chronicles of a Dyslexic Author, in which you describe the obstacles you faced as a pupil and later as a university student with undiagnosed dyslexia. Which obstacle was the worst?

You guys! Those of you without similar issues.

You mention in the book that you used to make up stories to entertain your classmates. Did dyslexia turn you into a writer?

I haven’t really thought about it, but I’m sure dyslexia played its part. It forced me to be twice as alert – to observe everything. To remain on the bridge that connected the real, which tortured me, with the imaginary, which soothed me. Does it sound tiring? It wasn’t. It was a natural process. I was left with the bad habit of reading behind words. Such trouble…

What was your biggest help during school?

The love and emotional security I received from both my parents, despite the enormous pressure – especially from my father. Also, the countless images from my childhood and the small rewards for every little thing I got right. I realised that if even one person – your father or mother – offers you love and safety, it’s enough.

Dyslexia, dyspraxia, dyscalculia – all those ‘dys’ words in special educational needs place the problem on the child. But could it be that the problem lies in the educational system itself – that it’s actually the system that’s quirky and maladjusted to each pupil’s particularities?

Yes, the educational system is the problem. Even the term ‘educational system’ suggests a control mechanism imposed on the pupil, rather than an open learning environment with freedom of expression and therapeutic imagination. It’s no coincidence that many students without special educational needs still end up struggling. Pupils often enter school healthy and happy, and graduate wounded, with incurable blemishes. What terrifies me is that this has now become the norm – it’s accepted and no longer shocks us.

In my book Beware of the Infants I describe a school: “Here lies the chamber of gases of deactivation, dehydration and sterilisation.” And a few lines later: “On the wall, like hunting trophies, hang the embalmed heads of teachers who didn’t conform.”

At the risk of sounding wacky – can we blame capitalism?

But of course! “Capitalism is to blame” is a tried-and-true alibi. Even those who defend capitalism use it. In any case, capitalism preaches “equal opportunities in education.” As if! What capitalism means by equal opportunities is anyone’s guess.

How could the educational system help children love reading?

I don’t think there’s a way – it’s all gone so wrong. Even talented teachers are caught between clashing rocks; I don’t know how they cope. Love of learning and reading requires work. It’s tied to the aesthetics of living, to the elegance of everyday life. It requires being initiated into questioning everything as a way of existing.

You were diagnosed around 45, almost by accident. What did you feel?

I was delighted! I realised it was something with a name, an identity, and that others had it too. It wasn’t just me – and there was no need for medication. It might sound strange, but it made me proud of what I had achieved up to that point.

If you can keep a secret, I actually love writing the first draft before editing it. I’d love to publish a book of uncorrected first drafts – shabby and raw. Maybe I will someday.”

Do you still enjoy reading, or have you been traumatised for life?

I enjoy reading tremendously. I still struggle, of course – if the book is long, dense, or lacks punctuation, I jump around the lines; the letters and the pages blur together. But no trauma is eternal – it only becomes everlasting if, in some way, it serves us.

And how do you handle writing difficulties?

They’re always there, but I pay them no mind. My writing always needs tons of spelling and grammar corrections. I’ve made huge progress, but the difficulties remain – as do the thought leaps. It’s no big deal; there’s always a way through. If you can keep a secret, I actually love writing the first draft before editing it. I’d love to publish a book of uncorrected first drafts – shabby and raw. Maybe I will someday.

What advice would you give to parents of children with special educational needs?

Never be disappointed in your children. Remember that all children – especially dyslexic ones – might struggle with reading but excel at ‘reading’ the non-verbal cues of their parents, and they’re seldom wrong. Your love and encouragement will take them far.

And advice for SEN pupils?

There’s no chance in the world they won’t achieve wonders in their lives. And one more thing: no effort – even one deemed a failure by others – is ever fruitless.

Why do you think your memoir was such a hit?

Because this book isn’t just a book – it’s an act of twinning yourself with diversity. It’s a reminder that denial isn’t a revolutionary duty but a way of behaving. It’s a meeting point with the part of us that refuses to give up, a shortcut from the main road to the beach. It’s a technique for sneaking under the bar while everyone else exhausts themselves trying to jump over it. It’s a compact tomorrow that expands beyond the conventional pages of fiction. It’s an irresistible reality with the widest wings imaginable – those gifted by imagination. It’s a hymn to failed attempts that bear fruit when you least expect it.

Let’s not forget the one thing all readers have in common: their diversity.

How did you deal with the fact that, as with dyslexia, in literature a (foreign) language often turns from a helpful tool into an obstacle?

There are no such obstacles. You make peace with what you can do, you ask for help, and all is well. You must be proud of what you can achieve – it’s never too little.

Is literary translation a leap of faith?

Yes, it’s a huge leap of faith – a unique experience of flying alongside someone else, overcoming difficulties while still in the air. And even if you don’t land at the same moment, you can still hear the voice of the one who landed first, guiding you precisely to places you never knew existed.

How did it feel watching your memoir turned into a theatre monologue? What did you think of the production?

It was perfect. I was deeply moved and, without meaning to, identified with the protagonist – sometimes feeling sorry for him, other times finding him really annoying! The theatre was sold out for two years. Audiences laughed and cried – and so did I, all five times I watched it. The credit goes to those young, talented people who did such an amazing job. Could they have done even better? I’m sure they could – and they will, as the play is going to be performed again soon.

There are also plans for an internationally produced animation of Chronicles of a Dyslexic Author. What other ways can we make the book’s message reach audiences that exclude themselves from reading?

By getting to know the author! Then people will realise he’s much better than the person who wrote the book – capable of far more impressive and creative things. He’s an unpredictable guy!

There are always obstacles – and that’s good, because it makes us want to overcome them.”

To what extent should a creator protect the wholeness of their work? Or, to reverse the question, when does an adaptation stop sharing roots with the original?

If the creator tries to protect the wholeness of their work, it only means one thing – that they don’t believe in it. There’s no such thing as wholeness. If the core of a work is alive and full of energy, it needs no protection.

Did you expect such success?

Not in a million years. I never expect anything – and that’s why I’m always surprised. It’s all a game, and it’s such an honour to have the unknown as your teammate.

Is there a way to move beyond the cliché “Greece = ancient ruins”?

Tunics, peploses, greaves – yes, we’re in trouble! You can’t imagine the torture of being shot at daily by your ancestors and never dying. They were such good marksmen. It’s tragic – sleeping in your helmet, your neck aching, your blood unable to reach your brain properly, while your favourite game is a version of musical statues: hiding deep in the earth, waiting to be discovered by archaeologists. If ancient Greece could turn from a refuge into a take-off strip, that would be a historic day – a heroic moment. We could even rewrite our national anthem.

Greek literature – and poetry in particular – was celebrated with two Nobel Prizes (Giorgos Seferis in 1963, Odysseas Elytis in 1979). Yet since then, little modern work has broken through in the English language. What hinders Greek literature’s extroversion toward the world?

There are always obstacles – and that’s good, because it makes us want to overcome them. I don’t even like the term ‘Greek literature’. It’s like a boiling cauldron that overflows. Many people throw in whatever they have to rekindle its fire, so they can admire their own shadows in the dark. Fortunately, everything eventually evaporates, and the fumes – belonging to no country, having no beginning or end – sometimes turn into clouds and take us by surprise. Even if someone refuses to listen, the thunder of that storm will wake them.

Still, I refrain from optimism, because sometimes we writers are the obstacles – our self-enclosed inwardness, our diffidence, our dystopia as a way of life, our pseudo-intellectualism. Being an author is not a role.

—

Giannis Paschos is a distinguished Greek author and Ichthyology professor. Born in 1954 in Giannena, his writing spans genres from poetry and novels to short stories and essays – all characterised by surreal imagery, emotional insight and a deft use of language that often bends convention. The Greek edition of Chronicles of a Dyslexic Author received the Anagnostis Literary Award in 2023 and a National Book Award in 2024. Alexandra Samothraki’s English translation is published by Stairwell Press (paperback, £10).

Read more

giannispaschos.gr

instagram.com/stairwellbooks/

@stairwellbooks.bsky.social

facebook.com/StairwellBooks

Author photo by Dimitris Collias

Alexandra Samothraki (born 1980 in Athens) holds a MA in Publishing from City University and a Diploma in European Theatre from the University of Kent. She was named Best Young Playwright in 2011 by the National Theatre of Greece for her play Jasmin Lair, and has been the UK correspondent of literary portal Anagnostis since 2011, writing opinion pieces, book reviews and interviewing the likes of Yoko Ogawa, George Saunders, Terry Eagleton and Juan Mayorga. Her crime novel Weighting of the Souls was published in Greece by Isnafi Publishing. She lives in Canterbury.