From heaven to earth

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“A fascinating and revelatory book. A penetrating combination of tremendous scholarship, imagination and sympathetic understanding.” William Boyd

One of the most striking characteristics of Socrates, as we know him from Plato, Plutarch, Xenophon, Cicero or Diogenes Laertius, and the numerous, yet exasperatingly fragmentary sources that survive, was his talent for convincing his interlocutors of his utter ignorance of any subject – his signature style was to present himself to the unwary as possessing a childlike curiosity and an equally virginal mind-slate as regards expert knowledge. A famous statement of his was that he knew only one thing, namely that he knew nothing. His method of analysis, of philosophical enquiry, was to start at the very beginning of the line of reasoning, no matter how simple or how evident it might seem, and to proceed with, once again, seemingly childlike steps to conceptual conclusions we are still struggling to decipher, fully grasp and understand.

The uninitiated would see this slow, humble approach as a mental weakness, as proof that he could be easily overmastered by powerful rhetoric, by grand sophist gestures of intellectual bravura. Their assumption that Socrates’ simplicity, his emphasis on the small things in order to attain those that were deemed great, was a sign of simple-mindedness, would lead to their downfall time and time again – dramatically, theatrically, utterly spectacularly. With quiet triumph, Socrates would unfailingly emerge as an astonished, wondrous sage, evincing a brilliance whose subtle, understated power would change the way that humankind has looked at itself and the world ever since.

Socrates believed that “the unexamined life was not worth living” and made structured questions his breath and heartbeat; central to his legacy was the maieutic or ‘Socratic’ method – what Aristotle identified as the first systematic methodology for ethics and metaphysics, for things beyond mere physical interest and analysis. It was a radical new way of perceiving not only the world, but also the capacity of the human mind to engage with it, to relate to existence itself from the perspective of a search for meaning, rather than of an epistemological explanation. With a flourish of poetic beauty, Cicero would describe Socrates’ unique intellectual achievement in his Tusculan Disputations in almost Promethean terms: “Socrates called philosophy down from heaven, and placed it in cities, and introduced it even in homes, and drove it to inquire about life and customs and things good and evil” – he brought down philosophy from the heavens of science to the earthly ethics of human life.

Socrates taught thinkers who came after him not only what to know, but especially how and why to search for what endows life with meaning, rather than for what describes the mechanics of existence.”

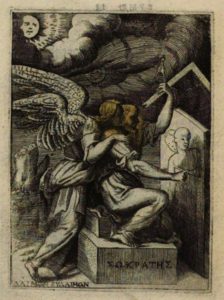

Engraving in Achille Bocchi’s Symbolicarum quaestionum de universo genere (1555), showing Socrates with his daimonion

Going against the prevalent ratiocentric, epistemological cosmologies and theories of the time, such as Anaxagoras’ Nous or the teachings of Archelaus or Melissus, which were arguably the equivalent of our own STEM mania today, Socrates taught thinkers who came after him not only what to know, but especially how to know, and why. How and why to search for what endows life with meaning, rather than for what describes the mechanics of existence. And yet we have nothing by his hand. There is absolutely no text, not even an iota of a sentence, that could possibly bear the signature Σωκράτης γέγραψε – Socrates ipse scripsit: Socrates himself wrote this. What we do have are above all chronicled episodes of his life, engrossingly told stories of Socrates rambling about Athens, meeting the young and the old, the rich and the poor, the educated and the ignorant, and engaging with each and all towards a common goal: the understanding of the purpose of and the way towards the good life. Or, as he would have preferred to say, towards the eudaimon bios, life in accordance to the godliness in things, what he termed his demon. What Socrates sought, to the end of his days, was the life of both virtue and happiness that was therefore true to its real, inherent meaning, and the only thing we have is the tale of how he went about it.

Plato’s Socratic dialogues are extraordinary, absorbingly readable, fascinating stories in this sense, possessing, beyond their philosophical complexity, peerless brilliance and uniqueness, a vividness that has enthralled readers unfailingly, repeatedly, almost wistfully. We are but shadows slinking through the words, the scenes and the milestones along that extraordinary path through life, lamenting the fact that much of it will always remain elusive, mysterious, beyond our reach, for all our yearning and longing for its vital companionship. Reading the Symposium, the Phaedo or the Phaedrus, will change your life, fill you with a hopefulness that can carry you through most anything; the Republic and the Protagoras will make you feel mad and exalted in turn, bring you to the brink of thoughts and words you did not know you possessed; reading the Apology, or rather living through it, is as transporting and devastating an experience as anything a human life can claim to contain.

And yet all the stories of Socrates that we have start, unlike Socrates’ own arguments, in media res, not at the beginning of his life, but somewhere in the middle, when Socrates was already the Socrates we (think we) know. In Socrates in Love: The Making of a Philosopher, Armand D’Angour sets out to provide us with the missing chapters, the missing links, the long-lost connections and crucial relationships. For D’Angour, Socrates’ earlier life, and not only his later philosophy, conceals both crucial mysteries and answers. “What can have inspired a young man of Socrates’ place and time to inaugurate a whole new style of thinking and to dedicate himself to a philosophical quest quite distinct from those thinkers who preceded him?” The question at the heart of this book is not simply what Socrates did, but why, “what, in short, made Socrates Socrates”. The answer lies in the story, reimagined, reconstructed, retrieved, retraced, of Socrates’ early life and the light it sheds on his maturity, the development of his thought and particular outlook towards life, and Socrates in Love is throughout an uncompromisingly and determinedly literary tale, as well as an historically unflinching account of this process of both being and becoming.

D’Angour does not shirk away from acknowledging the challenge of separating Socratic fact from the numerous rewritings that were intended to create and ensure a Socratic posterity. The clarity and persistence of his focus however creates a riveting correspondence and interplay between the two, which enables him to produce his own plausible version of events, one he hopes will reveal the unassailable reality underscoring this long history of fiction. Central to his argument is an intimately personal and unyieldingly scholarly evocation of Athens at the time, and of Greece as the broader, critical context of the so-called Golden Age. He does so with gusto, a muscular display of erudition, and a sense of urgent immediacy. As a result, Socrates in Love is fast-paced, robust and magisterial in tone, with an underlying adage theme, that of love as Socrates’ primum mobile, that gives it a mellow grace and fluidity.

We see Socrates as a man of remarkable endurance and bravery, distinguished for his unflinching sense of public duty, for his commitment to his fellow human beings [and] as a self-effacing bon viveur.”

D’Angour picks out scenes and episodes from textual accounts that survive to reconstruct without flamboyance, yet with a distinct feeling of momentousness, Socrates’ Stages on Life’s Way. He gives us the story of all the stories told by others, as well as the story of a very real life. We see Socrates as a man of remarkable endurance and bravery, distinguished for his unflinching sense of public duty, for his commitment to his fellow human beings; as a self-effacing bon viveur, whose exemplary education suggests a relatively prosperous and privileged family background. D’Angour conjectures against those who would have Socrates rise to prominence from poverty and obscurity: his father was connected to some of the most distinguished minds and public figures of the time, and he would have benefitted from the construction boom that followed the Persian Wars and from Pericles’ ambitious cultural plans for Athens. As a youth, Socrates could pay a princely sum for a papyrus by Anaxagoras, believing that he would find there the revelation he so much yearned for.

Socrates was “a strong and attractive young man… growing up in an elite Athenian milieu”, with aspirations “for heroic prowess on the battlefield and in political life”, very much like his peers. He had some of the finest tutors who taught him how to play the lyre and to dance (he was exceptionally disciplined in both his body and his mind), and who gave him a lifelong love and appreciation of literature and learning. He had the leisure to ponder; he was able to travel and meet some of the great figures of his time, who would mark him but also disappoint him – he was still to discover his own sense of direction. D’Angour aims to show how Socrates moved from public ambition and a fascination with the dominant doctrines of scientific materialism, to a radical new definition of philosophy that was both response and reaction, theory and practice, continuity and a daring break with what had come before or was presented then as a desirable model. Such a shift from pragmatism to ethics and eschatology was unqualifiedly revolutionary – and the cause of this shift of consciousness, of this deliberate choice of a non-linear, non-utilitarian path to a meaningful life lies at the crux of D’Angour’s own non-linear quest.

Socially, politically, intellectually, as it emerges from D’Angour’s highly immersive tableau, Socrates lived at a time strikingly and crucially akin to our own. Spin doctors and ideologists are the unmistakable, updated versions of Athens’ sophists and skilled demagogues; our denigration of intellectual acuity and of the educated mind, our rising espousal of populism and our unreflected endorsement of popular sentiment remain the same, with the tragic caveat that we have had more human history to learn from, and ought to know better. Historically, Socrates experienced first-hand and throughout his life the menace and the ravages of war, the toxicity of political power, alongside the inflated sense of ambition and expectation that follow periods of prolonged unrest and warfare. He was born towards the end of the Persian Wars and the start of Athens’ ascendancy as the leader of one part of the Greek world – with Sparta as the cultural, military, political other. The Peloponnesian War would mark his life in the starkest terms: he fought as a hoplite in numerous, bloody, often surreally incomprehensible battles and campaigns; he lived through the plague that would devastate the Athenian population and strew the city streets with corpses; he witnessed besieged enemies eating their own to survive; he was confronted with making sense of brutal politics and savage military decisions, senseless zealotry and the waste of human lives. At the heart of all this turmoil, were, above all, a man and a woman: Pericles and Aspasia. They are the figures in the carpet for what D’Angour presents as a daring thesis, one he is keen to bolster with vivid historical, cultural and textual evidence, especially the centrality of Eros (pointedly in the midst of Strife) as a civilising principle for the Greeks.

D’Angour is unafraid to hold strong views and to favour eclectic interpretations of facts or dates, to play with rubato with his sources, which makes the story he weaves together fresh and provocative, eminently haunting and engaging, full of tantalising tangentials. Indulgent and thorough, Socrates in Love is full of repeats and retakes, vast surveys of history and politics, and the stillness and slowness of very close readings. Socrates for D’Angour must have found himself at a crossroads like Hercules, where he made the most seminal, groundbreaking choice. A choice that embraced imperfection as well as the pursuit of excellence and perfection; a choice that placed inner freedom, reflection, service to one’s fellow human beings, the search for meaningfulness, for the Good, for integrity and authenticity, for being true to oneself, at the very heart of what makes existence possible and worthwhile. Instrumental to this choice was a woman, the Diotima of Plato’s Symposium, the glory of Zeus, as this presumed pseudonym suggests; Zeus was a common epithet for Pericles, and therefore Diotima, D’Angour argues, is no other than Aspasia. It is not a novel inference, yet D’Angour’s rich analysis, his comparative, contrastive, syncretic synthesis of facts, leads and the meaning that lies between the lines, makes it an exciting one. The socio-political and historical background that he gives it, his analysis of the personalities of Pericles, Aspasia, Alcibiades, the reconstruction of the human relationships, the living social circle that would have been formative for Socrates, is deeply engaging and will inspire equally animated private searches. Socrates in D’Angour’s hands is a man of his time as well as beyond his time – or even place.

Conversational and formidable, Socrates in Love is the story not only of a single man, but of the options available to humankind.”

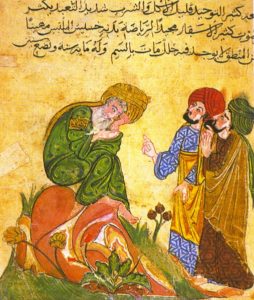

Illustration from a 13th-century Seljuk manuscript of Sughrat (Socrates). Topkapi Palace Library, Istanbul/Wikimedia Commons

The other dominant angle in Socrates in Love is the psychological one. D’Angour explores two particular idiosyncrasies of Socrates: his tendency to sometimes sit still for hours on end, in a state of what he terms “cataleptic seizure”, and his proverbial oddness and out-of-placeness – he was often called atopos by friends and foes alike. Conjoined to these is Socrates’ description of the inner voice he has been hearing since he was a child. Carefully, sensitively, D’Angour experiments with explanations, to conclude that the traumatic effect of the disciplinary methods of Socrates’ father most probably lie at the root of both. Yet as one reads Socrates in Love, especially from within the context of Athenian politics and the Peloponnesian War, which are a latent, almost muted spectre in Plato’s works, another interpretation also suggests itself.

Often compared in antiquity to the Trojan War, the Peloponnesian War would be clearer to us if approached in its causes, aftermath and dire conditions through the prism of WWI – and Socrates saw each and every aspect of that prolonged moment in time from a proximity that must have shaken a man of his sensibility, sense of human belonging and intelligence. It must have affected him dramatically, decisively, traumatically. We are told of how he developed a technique of “controlled retreat” at the first battle he fought in – the carnage-battle of Coronea, which he would later translate into a philosophical practice. His prolonged states of detached contemplation, his sense of exteriority to the world, may have been equally the result of post-traumatic shock – an ancient equivalent to shell shock. It may have caused him to create a separate space of reflection, removed from what threatened his pursuit and his understanding of meaning, and allowing a critical and very intimately empathic examination of life, a commitment to what one can only call humanity. It is an attitude perhaps very much similar in its general principles to Victor Frankl’s psychotherapeutic analysis of and response to the experience of Nazi concentration camps. To examine Socrates and his philosophy from that additional perspective would conceivably open valuable new readings, adding to the image we have of Socrates as an extraordinary thinker, or even as a funny old, Aristophanic man.

Socrates’ gentleness in his ceaseless effort to nudge and to prod us in order to awaken our humanity often goes unnoticed. His irony is his gadfly, always there “to help his fellow citizens to gain greater illumination about the purpose of their lives”, and about “how best to cultivate and train the… soul.” They are qualities that are celebrated throughout Socrates in Love, emphasised by the repeats and retakes, the many variations on a theme that D’Angour presents us with. Socrates’ definition of love, which is palpably real, an eschatological and an ethical ideal, as well as an intangible mystery; his choice of the life of the mind, which is a veritable shift of consciousness and of conscience for an Athenian of his time; his choice of the life of the simple man (Odysseus’ choice in Plato’s underworld), build up to a sustained motif: underwriting D’Angour’s fascination with Socrates the man, the thinker, the Athenian, is perhaps the injunction that Socrates’ choice is one that we should all crucially consider in our own times. Conversational and formidable, Socrates in Love is the story not only of a single man, but of the options available to humankind at that far removed moment in time, of critical assessments and positions that determined individual and collective fates – options and assessments that would be especially vital and urgent for us today.

Armand D’Angour is an Associate Professor of Classics at Oxford and Fellow and Tutor at Jesus College, Oxford. He is the author of The Art of Swimming and The Greeks and The New (winner of the Spectator Book of the Year 2011, shortlisted for the Runciman Award 2012), he has written widely about Greek and Latin poetry, music, and literature, and was commissioned to craft Pindaric odes for two Olympic Games (for Athens in 2004 and London in 2012). Trained as a pianist and cellist as well as a classicist, he has recently contributed to the rediscovery of the sounds of ancient Greek music. Socrates in Love is published by Bloomsbury in hardback and eBook.

Armand D’Angour is an Associate Professor of Classics at Oxford and Fellow and Tutor at Jesus College, Oxford. He is the author of The Art of Swimming and The Greeks and The New (winner of the Spectator Book of the Year 2011, shortlisted for the Runciman Award 2012), he has written widely about Greek and Latin poetry, music, and literature, and was commissioned to craft Pindaric odes for two Olympic Games (for Athens in 2004 and London in 2012). Trained as a pianist and cellist as well as a classicist, he has recently contributed to the rediscovery of the sounds of ancient Greek music. Socrates in Love is published by Bloomsbury in hardback and eBook.

Read more

@ArmandDAngour

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.