Hemingway in Havana

by Norman Lewis

Ian Fleming, then Foreign Editor of The Sunday Times, sent Norman Lewis to Cuba in December 1957. Fleming had recently met Lewis, and became a fan of his writing. Having been sent a proof-copy of The Volcanoes Above Us, he wrote to Lewis’s editor, ‘Volcanoes is a wonderful book… showing a fascinating mind and really startling powers of description and simile. I haven’t enjoyed a book so much since I can remember.’ Separately he wrote a letter with helpful criticism to Lewis, adding, ‘I am every time arrested by your genius for intellectual photography in prose.’

Fleming had another motive for sending a writer to Cuba. He was working for MI6, with a special interest in the Caribbean, where he had a house in Jamaica. Earlier than most, he realised that Castro would probably triumph, and considered the Secret Service’s intelligence-gathering inadequate. He reckoned that the adventurous, Spanish-speaking Lewis would do better.

Ernest Hemingway committed suicide three years after the meeting described in this article.

—

A CALL CAME THROUGH from Ian Fleming in London. We had made a loose arrangement for a meeting in Jamaica, but there was a change in dates. He asked how things were going, and I told him that they were going fairly well, adding that there was not a lot more to be done.

‘Have you talked to the Big Man?’ he wanted to know.

By this I understood that he meant not the President, but Hemingway. I told him that Hemingway had been ill, adding that [Havana Post editor Edward] Scott did not seem to feel that a meeting would be specially rewarding.

‘Never mind Scott,’ Fleming said. ‘Do your best to see him.’

I assured him that I would. Fleming said that he had just read The Old Man and the Sea, again, and had found it even better on second reading. He had the book open by the phone, and proceeded to read out a fairly long passage that he had found of special appeal.

A letter arrived from Hemingway next morning. It was neatly handwritten and formal in tone. He said he would be happy to see me at his farm, Finca Vigia, on the outskirts of the city, and would send his car to pick me up, suggesting the next afternoon for the visit.

Hemingway’s concern for his privacy was in strong evidence at his farm, the roof of the building being screened by a high fence, with a gate secured by a chain and an enormous padlock. The driver got out to unlock the padlock, drove the car through the gate, then stopped to go back and chain and lock the gate again. I was ushered into a large room, furnished in the main with bookshelves, where I found Hemingway, in his pyjamas, seated on his bed. He pulled himself to his feet to mumble a lacklustre welcome.

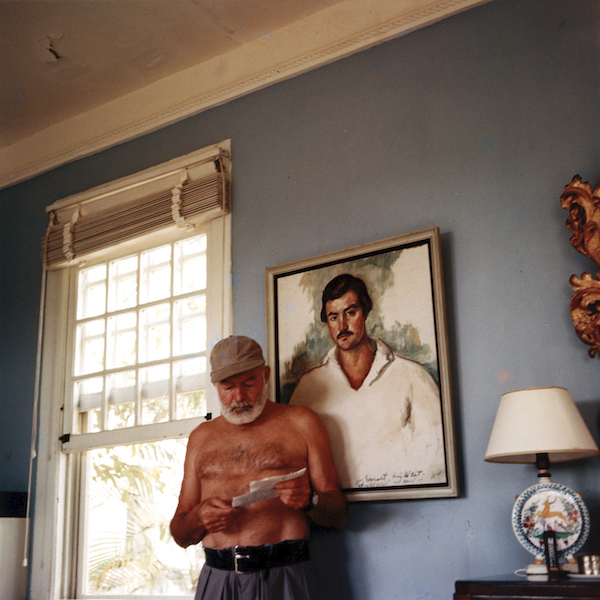

I was stunned by his appearance. At sixty years old he looked like a man well into his seventies, and he was in wretched physical shape. He moved slowly under the great weight of his body to find the drinks, pouring himself, to my astonishment, a tumblerful of Dubonnet, half of which he immediately gulped down. Above all, it was his expression that shocked, for there was exhaustion and emptiness in his face. This was an encounter that might have been dangerous and undermining to any young man in the full enjoyment of ambition and hope, because it presented a parable on the subject of futility. Hemingway’s mournful eyes urged you to accept your lot as it was, and be thankful for it.

It was hard to believe that anything Hemingway had set out to do had been left unachieved. Yet after all his conquests he seemed ready to weep with Alexander, and it was hard to believe that he would ever smile again.”

Some people, and Fleming and I were among them, regarded this man as one of the great writers of the twentieth century, and at this time, three years after he had been awarded the Nobel Prize, he had only just overtopped the pinnacle of his fame. He was a man who had gained all that life had to offer. He had crammed himself with every satisfaction, driven his body to the utmost, loved so many women, dominated so many men, hunted so many splendid animals. It was hard to believe that anything Hemingway had set out to do had been left unachieved. Yet after all his conquests he seemed ready to weep with Alexander, and, looking into his face, it was hard to believe that he would ever smile again.

We talked in a desultory and spiritless fashion, and it was Hemingway who brought up the subject of his publishers, showing little affection for them, and ready with criticism. He found them parsimonious, nervous of spending money on publicity, and this, he said, had had an adverse effect on the sales of his books in Great Britain, which were disappointing compared with those in the United States. He disliked the dustjacket of the English edition of The Old Man and the Sea. A leading artist had been commissioned at great expense to produce the American version, which he showed me, and it had to be admitted that it was vivacious enough to increase sales.

The release of this unexpected grain of information about his literary affairs led to my undoing. It seemed, mistakenly, to open a suitable opportunity – although Jonathan Cape had warned me that this was a topic to be approached with extreme caution – to mention that his publishers were eager to know whether anything new from him could be expected in the near future. The reaction was instant and hostile. A wasted and watery eye swivelled to watch me with anger and suspicion. What had I come for? What was it I wanted of him? In the coldest manner he asked, ‘Is this an interview?’ and I hastened to reassure him that it was not.

There was something in the scene with the faint remembered flavour of an episode in For Whom the Bell Tolls, featuring Massart, ‘one of France’s great modern revolutionary figures’, then Chief Commissar of the International Brigade – a ‘symbol man’ who cannot be touched. With time he had come to believe only in the reality of betrayals. With infallible discernment Hemingway had described this great old man’s descent into pettiness; and now I was amazed that a writer who had understood how greatness could be pulled down by the wolves of weakness and old age, should – as it appeared to me – have been unable to prevent himself from falling into this trap.

Suddenly the talk was of Scott, and there was a note of harsh interrogation. Did I know him well, and had I heard about the challenge? I admitted that I had. I added quite sincerely that I regarded it as childish and absurd.

He seemed appeased, almost amicable. ‘Take a look at this,’ he said. He put in front of me a copy of a letter he had sent to the Havana Post. In this, couched in the most conciliatory language, he had taken note of the challenge to a duel made by its Editor, Edward Scott. This he had decided not to take up, in the belief that he owed it to his readers not to jeopardise his life in this way.

I nodded approval. It was the best thing in the circumstances that he could have done. For all that I was surprised, and in some way disappointed at the wording of the letter, as I felt that his readers might have been left out of it.

The problem now was how Fleming’s demands – seeming more eccentric with every minute that passed – were to be satisfied. And yet Hemingway’s opinions on Cuba ought to have been worth listening to. He had gone there in search of ‘pay-dirt’ for his postwar fiction many years before, and remembering his passionate involvement in the Spanish Civil War and in the politics of those days, it was hard to believe that suddenly he had torn himself free from all involvement with those times, and that Cuba for him was nothing but a tropical setting for the pursuit of visiting film actresses and gigantic fish. He downed another half-pint of Dubonnet, yawned, and I got up to go. He followed me to the waiting car. All his anger had passed, and I imagine that he felt little but boredom. ‘A final word of advice,’ he said. ‘As soon as you get back to the hotel, I’d change that shirt.’

The shirt was a khaki affair, with convenient buttoning pockets of the kind it was hard to find in London at that time, and I had picked it up in an army-surplus shop in Oxford Street. ‘By their standards that’s a uniform,’ he said. ‘You could find yourself in a whole heap of trouble.’

I pointed out that I was wearing seersucker trousers with the shirt. ‘It doesn’t matter,’ he said. ‘It’s still a uniform the way they see it, and they make the laws. A lot of cops on this island with itchy trigger-fingers. They have a rebellion on their hands.’

There was nothing to be lost. I took the plunge. ‘How do you see all this ending?’ I asked. Comrade Massart’s cautious, watery, doubting eyes were on me again. ‘My answer to that is I live here,’ replied Hemingway.

In my letter to Fleming I wrote, ‘Finally I saw the Great Man, as instructed. He told me nothing but taught me a lot.’

Extracted from ‘A Mission to Havana’, first published in the Observer on November 15, 1981, now reproduced in A Quiet Evening: The Travels of Norman Lewis, selected and introduced by John Hatt (Eland, £25)

—

Norman Lewis (1908–2003) was the author of thirteen novels and thirteen works of non-fiction, mostly travel books. During the Second World War he spent three years in the Intelligence Corps in North Africa and Southern Italy. His diaries from that time produced material for his masterpiece Naples ’44, written in 1977. His groundbreaking 1968 article for The Sunday Times magazine, ‘Genocide in Brazil’, led to a change in Brazilian law relating to the treatment of Indians, and to the formation of Survival International, the influential international organisation which campaigns for the rights of tribal people worldwide. Until he reached his nineties Lewis remained an enthusiastic traveller to offbeat places. A Quiet Evening collects thirty-six of his best articles across a period of five decades, and is published in hardback by Eland alongside an extensive backlist of his non-fiction.

Read more

travelbooks.co.uk/norman-lewis

@ElandPublishing

John Hatt cut his teeth as a publisher’s rep, after which he wrote The Tropical Traveller. He then worked as Travel Editor of Harpers & Queen for ten years whilst setting up cheapflights.com. In 1982 he created Eland with the purpose of reviving exceptional travel literature, infuriated that he could not get any publisher to reprint Norman Lewis’s The Dragon Apparent.

johnhatt.com