Home at the asylum

by Isabel VincentIn the nineteenth century Roosevelt Island, then known as Blackwell’s Island, was crowded with more than a dozen prisons, a smallpox hospital, workhouses, and even a home for “wayward girls.” Municipal leaders in the growing metropolis across the river decided that Blackwell’s Island would be the perfect place to lock away the criminal, the indigent, and the insane, convinced that “the pleasant and glad surroundings would be conducive to both physical and mental rehabilitation.” In 1828, New York City purchased the island for $32,000 and, four years later, the Blackwell’s Island penitentiary and hospital opened.

When I moved to the island in 2010, nearly fourteen thousand people – many of them UN bureaucrats and émigrés from the former Yugoslavia – lived among the remnants of that sad history. There are still the ghostly skeletons of abandoned hospitals, and even the modern residential buildings, most of them completed in the 1970s, resemble correctional facilities, minus bars and barbed wire fencing. Inside, the stained carpets in the hallways smell of cigarette smoke and stale cabbage. By contrast, Edward’s building is one of the more elegant and well maintained, with a small army of solicitous doormen.

During the year I lived on Roosevelt Island, there were few restaurants and only a Starbucks and a supermarket that residents referred to as the “antique store” because many of the products were past their “best before” dates. The island, which is about eight hundred feet wide at its widest point, turns into a ghost town after dark. When I invited an eighty-year-old friend who had lived in Manhattan for most of her life to visit me, she looked suspiciously around a deserted Main Street at night, and tentatively asked where she might find the wine store.

“Astoria,” I said.

Returning to Manhattan on the tram, a fellow rider mistook her for a tourist and asked where she was from.

“Manhattan,” she deadpanned.

We had rented an apartment in a sprawling housing complex right past the Good Shepherd Church and the Roosevelt Island Garden Club, with its odd, labyrinthine plots, crowded in summer with a lush tangle of tomato vines, all manner of flowering shrubs, and a jumble of dusty lawn ornaments. But where my husband at least at first saw paradise, I began to focus on something entirely different, and I started to pine for the bustling, vibrant streets of Manhattan. There was something about Roosevelt Island that seemed to mirror my own sadness. A legless beggar on a hospital gurney regularly greeted commuters with a tin can when they emerged from the subway station. I was soon to discover that he was part of the community of amputees who were residents of the two rehabilitation hospitals that were somber reminders of the island’s grim past.

The brochures said nothing about 888 Main Street’s dark history as one of the most notorious institutions in nineteenth-century New York – a place that even Charles Dickens found too creepy to spend much time at.”

We lived in The Octagon, the site of the former New York City Lunatic Asylum. The apartments were massive, with stunning views of the Manhattan skyline. The building had a tennis court, an outdoor pool, an art gallery, and even a little shuttle bus that ferried residents to the subway and tram stations. In 2006, a Manhattan developer had transformed The Octagon into a luxury rental building, unusual for the island, complete with marble countertops, high ceilings, and designer fixtures in “the dramatic setting of an urban waterfront park.”

But the brochures said nothing about 888 Main Street’s dark history as one of the most notorious institutions in nineteenth-century New York – a place that even Charles Dickens found too creepy to spend much time at. “Everything had a lounging, listless, madhouse air, which was very painful,” Dickens writes in American Notes for General Circulation, after a truncated tour in 1842. “The moping idiot, cowering down with long dishevelled hair; the gibbering maniac, with his hideous laugh and pointed finger; the vacant eye, the fierce wild face, the gloomy picking of the hands and lips, and munching of the nails: there they were all, without disguise, in naked ugliness and horror.”

More than forty years later, the New York Times reported on thirty-five-year-old Ellen Drum, a patient who suffered from “melancholia” and had been at the lunatic asylum for nearly two years. She had left the asylum dressed in “only a calico dress and undergarments and stockings” and was presumed drowned in the river. Her body was never found. There was something chilling about the eerie silences that descended on The Octagon at night. In retrospect, it was probably the most appropriate place in New York City for a breakdown, which I was soon to have. “I feel a deep emptiness – like nothing I have ever known,” I wrote in my journal, shortly after arriving at the island. “I have to do something drastic to end this.”

The sadness stemmed from loneliness. Despite our moving to Roosevelt Island at his request, my husband still hated New York so much that every school holiday and summer vacation became excuses to leave town with our daughter Hannah. Sometimes he didn’t even need the excuse and left on his own. When his mother became ill in Canada, I tried to be sympathetic but he was gone for increasingly long periods. We had spent most of our savings moving to New York; my husband didn’t have a green card, so I had no choice but to work to support all of us. In the mornings, I took the subway to my midtown office, and came home late at night to a cold, too-big apartment, overlooking the lights of Manhattan.

I began to count on dinner with Edward as a much-needed respite. His apartment became a sanctuary.

***

The “melancholia,” to borrow a nineteenth-century phrase the New York Times used to describe the maladies of patients shuttered in the asylum where we now lived, had been let loose within the confines of those walls. It was now sure to spill over to the outside world. Maybe friends had already noticed the sharp tones we used to address each other. At work, Melissa probably suspected. Why else was she so respectfully silent during my very uncomfortable phone calls home – conversations (could I even call them that?) that involved screaming on the other end and me trying unsuccessfully – in the middle of the newsroom – to calm the drama du jour in strained sotto voce.

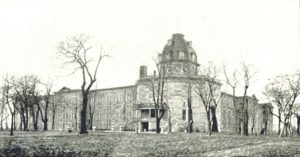

The Octagon in 1893, six years after Nellie Bly’s Ten Days in a Mad-House. British Library/Wikimedia Commons

In some ways, I identified with Nellie Bly, the investigative reporter who went undercover at my madhouse in 1887 and wrote a series of exposés for Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World. After ten days at the psychiatric hospital, she documented forced meals of spoiled food and ice-cold baths where prisoners were required to stand in long lines and wash themselves in the dirty water left by their fellow inmates.

Bly wrote about how prisoners from the nearby penitentiary even doubled as orderlies, keeping inmates in check through savage beatings. Among Bly’s observations, recorded in her book Ten Days in a Mad-House, which I had recently read, “From the moment I entered the insane ward on the island, I made no attempt to keep up the assumed role of insanity. I talked and acted just as I do in ordinary life. Yet strange to say, the more sanely I talked and acted the crazier I was thought to be.”

Well, maybe things weren’t as bad as all that but, like Bly, I was an investigative reporter who had also entered The Octagon undercover – when we moved in I was pretending that everything was all right with my life. But as soon as I began to get a grip on reality and reclaim myself, “the crazier I was thought to be.” When I brought up divorce with my husband, I was taken aback by his response. Was I mentally ill, menopausal? Had I had my thyroid checked lately? Perhaps I needed a psychiatrist, antidepressants? What about yoga? Bly’s statement ricocheted through my brain.

I’m not sure I did a good job explaining any of this to Edward. On that fateful Sunday afternoon I spent a lot of time crying my way through the bourbon, sounding incoherent even to myself. Edward listened and, at one point, rose to refill our glasses, having forgotten that we had already consumed the last of the bottle. I looked out his living room windows at the lights in the buildings across the water. It was already dark and I knew it was time to go home. Even in my leave-taking, though, there was something comforting. I guess I knew that after the drama, Edward would always be there. As he escorted me to the elevator, holding the door open with his outstretched cane, he said, “Let’s have dinner soon, OK?”

A couple of days later, I received a phone call from Edward’s daughter Valerie. Edward had told her everything about my crisis. She told me he was distraught, mostly because he felt there was nothing he could do to help me. As I listened, I became upset with myself for having put Edward under so much stress. “He’s very worried about you,” said Valerie.

But Edward never conveyed his worries to me. He never dwelt on my situation, rarely offered any specific marriage advice, never interfered. On occasion, he would sigh and shake his head. “It’s a bloody shame,” he would say, knowing that I was the only one who could solve my problems.

From Dinner With Edward (Pushkin Press, £12.99)

Isabel Vincent is a Canadian investigative journalist and award-winning author who writes for the New York Post. During the 1990s she was a foreign correspondent for the Globe and Mail and covered the conflicts that led to the Kosovo War. She has written several books for which she has received prestigious honours, including the Canadian Association of Journalist’s Award for Excellence in Investigative Journalism and the National Jewish Book Award in Canada for Bodies and Souls. Her writings have also appeared in the New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine, L’Officiel and Time. She lives in New York. Dinner With Edward, her memoir about unexpected friendship, breaking up and moving on, is published by Pushkin Press.

Isabel Vincent is a Canadian investigative journalist and award-winning author who writes for the New York Post. During the 1990s she was a foreign correspondent for the Globe and Mail and covered the conflicts that led to the Kosovo War. She has written several books for which she has received prestigious honours, including the Canadian Association of Journalist’s Award for Excellence in Investigative Journalism and the National Jewish Book Award in Canada for Bodies and Souls. Her writings have also appeared in the New Yorker, the New York Times Magazine, L’Officiel and Time. She lives in New York. Dinner With Edward, her memoir about unexpected friendship, breaking up and moving on, is published by Pushkin Press.

Read more

@isareport

@PushkinPress

Author portrait © Zandy Mangold