I-land

by Lorna Goodison

“A consummate essayist.” Margaret Busby

As a small child, I did not really have a very strong sense of being on an island. Maybe that is because I was born in the city of Kingston, which back then was a busy bustling metropolis, where something exciting was always happening. Kingston was no sleepy island outpost when I was growing up there. Every important person in the world seemed to pass through ‘Town’ as we called it, from Paul Robeson to Winston Churchill, the Bolshoi Ballet, Marion Anderson, George Bernard Shaw, Zora Neale Hurston, Sammy Davis Jr, Duke Ellington and every single member of the royal family. It was only after I began to visit my mother’s birthplace, where I would bathe in the river named for her family and roam freely through the bush enjoying the pastoral delights of rural Jamaica with my cousins, that I began to think of myself as being more than a Kingstonian.

As for always looking longingly at the horizon and wondering what was beyond it – as people who live on islands are thought to do – I did not do much of that when I was a child. If I wondered what was over the horizon, it was only because my mother’s sisters had emigrated to Montreal, Canada in the 1930s and they would send us letters and parcels that came from a faraway place referred to as ‘abroad’.

If I had a sense of being on an island at all, it was from the way in which the people around me always described Jamaica as ‘the Island of Jamaica’, or ‘Our Island Home’. Also, all the songs I heard or sang about Jamaica had ‘island’ in them. Perhaps my most vivid idea of what it was to live on an island came from my mother, who showed me that on the map of the world, Jamaica is shaped like a swimming turtle, so I got the point about being surrounded by water.

My engagement with the sheer beauty and the chaos of the island never goes away… The colours, the music, the speech, the smells, the intensity of everything, good and bad. There is nothing watered down in Jamaica.”

The boundary around my known world was more the boundaries set by humans, particularly by my family. I’m one of nine children. I grew up surrounded by a sea of people.

But I always loved the sensuousness of island life. I love ‘sun-hot’, as Jamaicans say. I enjoy bathing in the Caribbean Sea and I am certain that there are no fruits in the world that taste as good as Jamaican naseberries, mangoes, pineapples, star apples and sweetsops. Seriously nothing in the world tastes as good as a plate of Jamaican fruit. I believe that Jamaica is one of the most beautiful places in the world and I have been known to burst into tears at the sight of the Blue Mountains. In my best dreams I’m bathing in the warm Caribbean as I gaze up at the Blue Mountains. My engagement with the sheer beauty and the chaos of the island never goes away, and it drives a great deal of my work. The colours, the music, the speech, the smells, the intensity of everything, good and bad. There is nothing watered down in Jamaica, it is all concentrated and I try to draw on that.

But one of the downsides to island life is that it can be very limiting: circumscribed, provincial, petty, tribal.

Life in larger land masses such as the USA, Canada and Europe allows for much greater variety, complexity and freedom of movement. Living away from island society also allows you to change and grow and reinvent yourself away from the prying and often judgmental eyes of people who presume that because they have known you for much of your life, they are qualified to assess just what you are capable of, and to decide just how far you should go.

One of the many things I love and admire about the USA and Canada is the sense of possibility that abounds in such big places. This sense of possibility is not as available to people in island societies, and many people who experience difficulty finding ways to thrive in small island communities often grow and flourish remarkably well upon finding themselves in large metropolitan centres.

Still, I carry my islandness with me wherever I go. l always miss the sea when I’m away from it and I like to know that it is close by even if I cannot actually see it. I will even settle for a small man-made body of water – a sort of sea surrogate – like the one set down in the marshlands behind the apartment complex called The Ponds in Ann Arbor, where I lived for years. These days I am lucky to find myself living beside the Salish Sea in Halfmoon Bay, British Columbia, for being by the sea makes me feel more whole, more balanced somehow. I’d like to think it might be ‘deep calleth unto deep’, and all that, or maybe it is just that people who come from islands have this need to be near the water.

One of the things I always have to explain to students in North America is that Caribbean island nations are far from being homogenous. That, in fact, they are quite proud of their differences, often in contentious ways. Still, islands in the Caribbean, the Pacific and the North Atlantic do have shared characteristics. Being surrounded by water – especially in the old days before aeroplane travel – meant it was not easy to get away. That did not stop people from trying, and as a child I remember sometimes hearing stories about men stowing away in the dark holds of those big ships that docked in Kingston Harbour.

The ancestors of the majority of Jamaican people were forcibly brought to the island on big slave ships. They were captured in Africa and transported in appalling and inhumane conditions and brought as units of unpaid labour for the island’s sugar plantations, and for this reason slavery has supplied the ongoing metaphor for almost all worthwhile Jamaican creative endeavours. From the Maroons – including Nanny of the Maroons about whom I write in many of my poems – who waged relentless resistance against plantation slavery, to Rastafarians who took up the fight against ‘Babylon’, that is, the British colonial system, Jamaican culture continually references slavery.

Being surrounded by the sea also means being constantly aware of this great force that cannot be controlled by humans.”

Jamaican musicians like Bob Marley, Peter Tosh, Bunny Wailer, Burning Spear, Culture, Ibo Cooper of Third World, Tony Rebel, Steel Pulse, Damian ‘Junior Gong’ Marley, Chronnixx and Queen Ifrica, all have at the heart of their project this focus on what Rastafarians call ‘Truth and Right.’ I think that this concern for justice is born out of an island mentality; you are there in this cut-off place, you might not be there of your own volition, but you are surrounded by the sea, marooned, so to speak, and you are going to have to stay there and actively try to work it out. I believe that is what I am also trying to do in my work.

Being surrounded by the sea also means being constantly aware of this great force that cannot be controlled by humans. Life on an island is always punctuated by reports of people being lost to the sea. The sea is always there in the background as a force both benign and dangerous, it feeds you and it kills you and it is all around you.

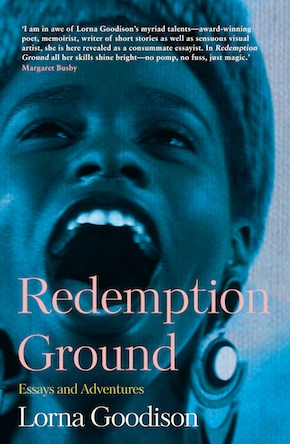

from the essay collection Redemption Ground (Myriad Editions, £9.99)

Lorna Goodison is the Poet Laureate of Jamaica, and the author of nine collections of poetry, three collections of short stories and an award-winning memoir, From Harvey River: A Memoir of My Mother and Her People. Her Collected Poems was published in 2017. Her many awards include the Commonwealth Poetry Prize, the Musgrave Gold Medal from Jamaica and the Windham Campbell Literature Prize. Professor Emerita at the University of Michigan, where she was the Lemuel A. Johnson Professor of English and African and Afroamerican Studies, she now lives in Canada. Redemption Ground is published by Myriad Editions.

Lorna Goodison is the Poet Laureate of Jamaica, and the author of nine collections of poetry, three collections of short stories and an award-winning memoir, From Harvey River: A Memoir of My Mother and Her People. Her Collected Poems was published in 2017. Her many awards include the Commonwealth Poetry Prize, the Musgrave Gold Medal from Jamaica and the Windham Campbell Literature Prize. Professor Emerita at the University of Michigan, where she was the Lemuel A. Johnson Professor of English and African and Afroamerican Studies, she now lives in Canada. Redemption Ground is published by Myriad Editions.

Read more

National Library of Jamaica: Lorna Goodison