In too deep

by Pierre Lemaitre

“A really excellent suspense novelist.” Stephen King

Having laid my son-in-law out for the count, I continue on my way. From the outside, anyone might think I’ve lost all feeling.

Once upon a time, I knew myself well. I mean that my behaviour rarely surprised me. When you’ve experienced most situations, you also learn the correct responses to them. You even notice the circumstances where self-control isn’t necessary. Family scuffles with pricks like my son-in-law, for example. Past a certain age, life starts repeating on itself. The thing is, anything you do or don’t acquire through experience alone you can learn in two or three days’ worth of management seminars, with the aid of grids that class people according to their character. The process is practical, it’s playful, it boosts your spirits at little cost, and it makes you feel clever. It even lets you imagine you might become more efficient in the workplace. In short, it soothes you. Over the years, trends have changed, and so have the criteria. One year you get tested to see if you are methodical, energetic, cooperative or determined. The next it might be to check if you’re hardworking, precocious, pioneering, persistent, empathetic or blue-sky-thinking. If you have a new coach, it turns out you are protective, directive, putative, emotive or responsive, while the next session you attend helps discern whether you’re action-, method-, idea- or procedure-oriented. The whole thing’s a hoax, but no-one can get enough of it. It’s like with horoscopes, where you always end up identifying traits that match your own. The reality is that you never know what you’re truly capable of until you find yourself in extreme circumstances. Right now, for example, I’m surprising myself a lot.

My telephone rings as I’m leaving the metro. I’m always wary when things are moving too fast, and things are moving too fast now.

“My name is Albert Kaminski.”

A pleasant, open voice, but it’s too soon. Come on, I only posted the ad this morning and already…

“I believe I can offer you what you’re looking for,” he tells me.

“And what is it I’m looking for?”

“You’re a novelist. You’re writing a book that revolves around a hostage-taking and you need practical, concrete advice. Precise information. Unless I misread your advertisement?”

He is well-spoken and not at all fazed by my direct question. Seems solid. I get the impression he is calling from a public place where he has to keep his voice down.

“And you have personal experience in this field?”

“Of course.”

“That’s what everyone says.”

Kaminski is all over the place. He’s in free fall. We could be cousins. Our fall might not be the same, but our desperation is. I back away. I need strong people: skilful, operational.”

“I’ve experienced several real hostage situations, all with different circumstances and in the recent past. Last few years. If your questions are about how this sort of operation unfolds, then I think I’ll be able to answer most of them. If you want to meet me, here’s my number: 06 34…”

“Wait!”

There’s no doubt he’s skilled. He speaks calmly, he doesn’t get annoyed by my deliberately aggressive questions, and he’s even managed to wrest back the initiative, since I’m the one requesting a meeting. This could well be my guy.

“Are you free this afternoon?”

“Depends what time.”

“You tell me…”

“From 2.00 p.m.”

It’s a date. He suggests a café near Châtelet.

***

Châtelet.

It’s sort of a brasserie, but with leather armchairs. The chic end of shabby-chic. The kind of place I would have loved when I had a salary.

When I see him, the first thing that comes back to me is his voice. It seemed borrowed, as if speaking irritated him. He barely stirs, or if he does it’s very subtle, like slow-motion. He’s thin. I find him very strange-looking. Like an iguana.

“Albert Kaminski.”

He hasn’t stood up, just leaned forward a little, holding out his hand indifferently. First impression: -10. It’s a poor start, a major handicap, and I don’t have much time to lose. I have objectives.

I sit straight-backed at the edge of the armchair, no intention of staying for long.

He’s the same age as me. We sit in silence as the waiter takes our order. I try to figure out what is bothering me about him, then it hits me. He’s a druggie. This is a tricky area for me, because, as astonishing as it might sound, I’ve never touched them. For a man of my generation, that’s nothing short of miraculous. So when it comes to drugs, I’m not exactly a natural, but I think I’ve put my finger on it. Kaminski is all over the place. He’s in free fall. We could be cousins. Our fall might not be the same, but our desperation is. I back away. I need strong people: skilful, operational.

“I used to be a commandant in the police,” he begins.

His face is creased, but his eyes are dry. Nothing like Charles. Alcohol ravages you in a different way. What’s he on? I don’t have a clue, but it’s clear that this inspector has lost none of his self-esteem.

Latest score: -8.

“I spent most of my career doing special operations at R.A.I.D. That’s why I answered your ad.”

“Why aren’t you there anymore?”

He smiles and looks down.

“I don’t mean to pry, but how old are you?” he says.

“More than fifty, less than sixty.”

“Roughly the same as me, then.”

“What’s that got to do with anything?”

“By the time you get to our age, you can spot certain types right away: gays, racists, fascists, hypocrites, alcoholics. Drug addicts. And you, Monsieur…?”

“Delambre. Alain Delambre.”

“… I can tell you see me for what I am, Monsieur Delambre. So that’s my answer to your question.”

We smile at each other. -4.

“I used to be a negotiator. I was struck off from the police eight years ago. Professional misconduct.”

“Anything serious?”

“There was a fatality. A woman, a desperate case. I was a little high. Ecstasy. She threw herself out the window.”

Anyone who can cancel out a ten-point deficit in just a few minutes is someone capable of faking compassion, proximity, similarity. In short, a good cheat. Either that or they’re extremely sincere.

“And you think I can trust someone like you?”

He thinks for a moment.

“That depends on what you’re looking for.”

Sooner or later, this guy will end up in the slammer or in a dealer’s wheelie bin. In terms of rates, that gives me some bargaining power.”

He must be taller than me. Standing up, I reckon five foot nine. He’s broad-shouldered, but everything tapers in the further down you get, like someone from the nineteenth-century with consumption.

“If you really are a novelist and you’re looking for information about hostage-taking scenarios, then I meet your needs.”

The subtext is clear: he’s no fool.

“What does R.A.I.D. stand for?”

He frowns in total despair.

“No, seriously…”

“Research, Assistance, Intervention, Dissuasion. I was in charge of the dissuasion bit. At least I was until I was given the heave-ho.”

He’s not bad. Even if the two of us do make for a right old pair of sad cases. How does he make his living? He’s poorly dressed. Seems an opportunist type, in poor health: can’t imagine he turns much down work-wise. Sooner or later, this guy will end up in the slammer or in a dealer’s wheelie bin. In terms of rates, that gives me some bargaining power. The thought of money overwhelms me with sadness. Mathilde’s face enters my mind, followed by Nicole, my wife who doesn’t want to sleep by my side. I am tired.

Albert Kaminski looks at me with concern and offers me the jug of water. I’m struggling to catch my breath. I’m taking this too far, it’s all going too far.

“Are you alright?”

I down a glass of water and shake myself.

“How much do you charge?”

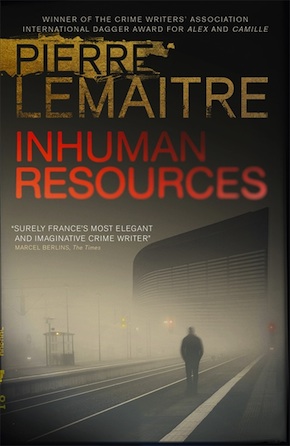

from Inhuman Resources (MacLehose Press, £16.99)

Pierre Lemaitre was born in Paris in 1951. He worked for many years as a teacher of literature before becoming a novelist. He was awarded the Crime Writers’ Association International Dagger, alongside Fred Vargas, for Alex, and as sole winner for Camille. In 2013 his novel Au revoir là-haut (The Great Swindle, in English translation) won the Prix Goncourt, France’s leading literary award. His other novels include Blood Wedding, Rosy & John and Three Days and a Life. Inhuman Resources, translated by Sam Gordon, is published by MacLehose Press in hardback and eBook.

Read more

@PLemaitreAuteur

Author portrait © Thierry Rajic/Figure

Sam Gordon is a translator from French and Spanish. His previous translations include works by Karim Miské, Sophie Hénaff, Timothée de Fombelle and Annelise Heurtier.