On ghosts and grace

by Brett Marie

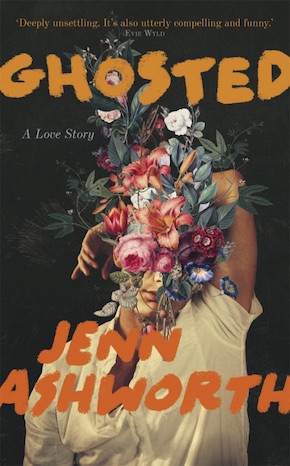

“Ghosted is fresh, darkly funny and exceptionally moving… Ashworth folds grief and anger and love into every line.” Claire Fuller

At the outset of our email chat about her new novel Ghosted, when I tell her how deeply I connected with her story, Jenn Ashworth accepts my heartfelt praise with the comment: “It’s all I want, really, when people read my books – just to feel like they’ve been acknowledged and offered something half-useful.” It’s a modest statement of purpose, but deceptive in its simplicity, given how difficult it is to reach every reader, no matter what their walk of life. And in fact, to be frank, it’s a bit over-modest, I believe, given how rarely a book succeeds as completely as Ghosted does.

Though engaging, the book’s opening is hardly grandiose. From its inciting incident, Ghosted could pass as a straight mystery novel: Laurie Wright returns to her cramped high-rise flat one evening to find that her husband Mark has vanished. All of his belongings have been left behind, and so Laurie considers the possibility of foul play. But she can’t be sure, and as she stumbles through her narrative, jumping back to fill us in on her relationship with Mark, leading us through her day-to-day routine (work, visits with her ailing father, drinking, fretting), it becomes clear early on that we readers can’t be sure of very much.

As with any good mystery, the questions pile up. Could Mark have been bumped off? Why didn’t he tell Laurie how he’d been fired from his job? Perhaps most importantly though, why does Laurie take five weeks after his disappearance to call the police?

Further confounding our perceptions is the realisation that Laurie is an unreliable narrator. Not that Laurie herself would necessarily agree with that label. When she omits facts in her police statements, when she leaves things unsaid in a heart-to-heart with her mother-in-law or with her father’s caretaker, she’ll spend the next paragraph explaining the deception to the reader. But her willingness to divulge important information only goes so far. Other crucial facts trickle out sporadically, often in asides during seemingly unrelated passages, and we’re left with the sense that Laurie’s full, ugly story will come out only when she’s good and ready.

The novel’s full title is Ghosted: A Love Story, but coming from Ashworth’s pen it could have been any kind of story. The Lancashire native’s previous work has veered from black humour to drama to memoir. Her last novel, 2016’s poignant masterpiece Fell, even starred a pair of ghosts, so when Laurie flashes back to her first meeting with Mark at a wedding reception where the future couple fell into conversation with Joyce, a professional psychic, the reader can’t rule out the possibility that back in the present the couple’s reunion might take place with Joyce as the go-between.

Like a master magician bending balloons into all manner of animal shapes with a few flicks of the wrist, Ashworth knows how to give just the right twists to bring a phrase to life”

Whether or not Mark will turn up again in ectoplasmic form, Laurie’s life is already filled with spectres. There’s her father, a shell of his former self who haunts her with dementia-induced rants about her deceased mother’s imaginary infidelities. There’s the phantom suspicion, flitting around the edges of Laurie’s thoughts, that Mark might have been having an affair with the Wrights’ upstairs neighbour, Laurie’s former friend Katrina. There is of course Mark himself, who makes his presence felt in every page by his very absence. And there’s something else, some unnameable presence, that weighs down ever more heavily on Laurie as her grief-induced downward spiral goes on.

A writer must be careful when spinning a yarn such as Laurie’s, lest she fall into the classic trap of Loser Lit: a character who spends her time moping, no matter how valid her reasons, runs the risk of alienating her reader. But here is where this author’s supreme talent for prose writing comes into play. Like a master magician bending balloons into all manner of animal shapes with a few flicks of the wrist, Ashworth knows how to give just the right twists to bring a phrase to life. It’s a deft sleight of hand, whereby a few choice words can invoke dread (describing television images of the mother of a missing child, “white and remote in the great unknown of her daughter’s absence”), a laugh (a past argument over a colander they use to pour boiling pasta in their tiny kitchen sink pits Laurie, who keeps getting scalded by the splashing water, against Mark, “whose hands were made of asbestos”), or a lump in the throat (“There’s no formula or physics that makes sense of the human heart when it longs for something, I have learned”).

Of course, as with any skill, it takes practice to master Ashworth’s blend of keen observation and wit. And while a quartet of novels beginning with A Kind of Intimacy have given the author ample space to refine her literary craft, in retrospect it’s what she observed amid the real-life depression she undertook to document in her experimental memoir, Notes Made While Falling, that I suspect provided the dry run for this fictional outing.

“Yes,” she replies when I ask about it. “Ghosted is one more version of Notes, I think. Laurie’s story isn’t mine, of course, but I do know about her feelings.” But then, Laurie spends a good deal of her time being something less than her best self. Ashworth appreciates the uneasy parallels. “I think what I wanted most in Ghosted was to demonstrate the way when we are most in need of love, we tend to act in ways that are least likely to attract it, and that it is my perhaps naive belief that people are generally intolerable at exactly the same moment as they most need to have grace extended to them.”

I’m reminded of the state Ashworth described reaching in Notes, of depraved post-partum depression, drinking, withdrawing down internet rabbit holes. I could see her flailing for what it was on the black and white of the page; I can’t say whether I would have been so perceptive in person. Ashworth muses along a similar line when she talks about grace: “I’m not sure I am all that good at doing it in real life, but I do hope I can offer some of that in my fiction.”

Ashworth’s personal descent wasn’t pretty, and it created a crisis of confidence: “That’s an idea that I tussled with a lot while writing Notes,” she tells me. “Can someone who is unwell, who is broken or flawed or has murky and muddy intentions offer anything to a reader that is valuable? I do have a moral question that plagues me. Do you have to be good to make something good? And if the answer is no, then how does the good that we find in our art get into it if the artist isn’t capable of putting it there? I don’t know the answer to that question, by the way.”

Yes, it’s often satisfying to have a villain get his comeuppance, but it’s a far more lasting comfort to see our flaws in other people, and to see those flaws forgiven when, like us, those people come up short.”

But in making herself vulnerable, in offering her less-than-heroic story, Ashworth was able to give comfort to other women who shared with her a common experience – one that isn’t often discussed in the open. “There’s SUCH a lot of silence around certain types of loss – or even certain types of feelings – that we’re shamed for having them, and in my experience all that does is heap misery upon misery.” Indeed, to revisit her past in all its gory detail in prose was an act of grace in itself, as the work of art she created became a kind of receptacle into which the right reader could put their own meaning and experience. The writer Zoe Hannon (who had experienced the resonating trauma of a “bloody birth story” like the one Ashworth documented) said of Notes: “… there’s a generosity and deliberate space to this book that allows time for moments of ‘me too!’ recognition and for a folding in of the reader’s experience. It feels collaborative in a way that only real art can. It is engaging and that engagement is hard, rewarding work.”

And with Ghosted she repeats that feat on a broader scale. Mark’s disappearance will turn out to be an act of cruelty – at least on its face – and more than once as she deals with her pervasive sense of loss, Laurie will commit sins that compound it. Moreover everyone around her, it seems, will have a turn to be selfish or unkind in her eyes. But everyone around her is human; by the end of the book, Ashworth will pass judgement on them all, and will find ways to tip the scales in their favour.

It’s a generous act for her audience, since among this varied cast, a reader will likely find commonality with at least one of her vividly drawn characters. Yes, it’s often satisfying to have a villain get his comeuppance, but it’s a far more lasting comfort to see our flaws in other people, and to see those flaws forgiven when, like us, those people come up short. What sets Ghosted apart from other fiction – indeed, what sets Ashworth above so many of her contemporaries – is that immense empathy, that willingness to forgive.

Ghosted: A Love Story is what it claims to be. With that love comes loss, grief and mourning, mistreatment and neglect, and all the other ghastly things that make life so often hard to bear. Laurie’s journey will take readers to a dark place indeed, but it’s a place worth visiting, and with Ashworth as their guide they’ll take something more than half-useful with them when they come out the other side.

Jenn Ashworth was born in 1982 in Preston. She studied English at Cambridge and since then has gained an MA from Manchester University, trained as a librarian and run a prison library in Lancashire. She now lectures in Creative Writing at the University of Lancaster. Her first novel, A Kind of Intimacy, was published in 2009 and won a Betty Trask Award. For her second, Cold Light (2011), she was chosen by BBC’s The Culture Show as one of the twelve Best New British Novelists. Her most recent novels The Friday Gospels (2013) and Fell (2016) and the memoir Notes Made While Falling (2019) were published to resounding critical acclaim. She lives in Lancaster with her husband, son and daughter. Ghosted is published by Sceptre in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Jenn Ashworth was born in 1982 in Preston. She studied English at Cambridge and since then has gained an MA from Manchester University, trained as a librarian and run a prison library in Lancashire. She now lectures in Creative Writing at the University of Lancaster. Her first novel, A Kind of Intimacy, was published in 2009 and won a Betty Trask Award. For her second, Cold Light (2011), she was chosen by BBC’s The Culture Show as one of the twelve Best New British Novelists. Her most recent novels The Friday Gospels (2013) and Fell (2016) and the memoir Notes Made While Falling (2019) were published to resounding critical acclaim. She lives in Lancaster with her husband, son and daughter. Ghosted is published by Sceptre in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

jennashworth.co.uk

jennashworth82

@jennashworth

Author portrait © Martin Figura

Brett Marie, also known as Mat Treiber, grew up in Montreal with an American father and a British mother and currently lives in Herefordshire. His short stories and other writing have appeared in publications including The New Plains Review, The Impressment Gang, PopMatters and Bookanista, where he is a contributing editor. His debut novel The Upsetter Blog will be released in Autumn 2021 by Owl Canyon Press.

Read more

Facebook: Brett Marie

@brettmarie1979

bookanista.com/author/brett-marie/