Joe Buck!

by James Leo HerlihyIn his new boots, Joe Buck was six-foot-one and life was different. As he walked out of that store in Houston something snapped in the whole bottom half of him: A kind of power he never even knew was there had been released in his pelvis and he was able to feel the world through it. Brand-new muscles came into play in his buttocks and in his legs, and he was aware of a totally new attitude toward the sidewalk. The world was down there, and he was way up here, on top of it, and the space between him and it was now commanded by a beautiful strange animal, himself, Joe Buck. He was strong. He was exultant. He was ready.

“I’m ready,” he said to himself, and he wondered what he meant by that.

Joe knew he was no great shakes as a thinker and he knew that what thinking he did was best done looking in a mirror, and so his eyes cast about for something that would show him a reflection of himself. Just ahead was a store window. Ta-click ta-click ta-click ta-click, his boots said to the concrete, meaning power power power power, as he approached the window head on, and there was this new and yet familiar person coming at him, broad-shouldered, swaggering, cool and handsome. Lord, I’m glad I’m you, he said to his image – but not out loud – and then, Hey, what’s all this ready crap? What you ready for?

And then he remembered.

***

When he arrived at the H tel, a hotel that not only had no name but had lost its O as well, he felt the absurdity of anyone so rich and hard and juicy as himself ever staying in such a nameless, no-account place. He ran up the stairs two at a time, went to the second floor rear and hurried into the closet, emerging seconds later with a large package. He removed the brown paper and placed on the bed a black-and-white horsehide suitcase.

He folded his arms, stood back and looked at it, shaking his head in awe. The beauty of it never failed to move him. The black was so black and the white so white and the whole thing so lifelike and soft, it was like owning a miracle. He checked his hands for dirt, then brushed at the hide as if it were soiled. But of course it wasn’t, he was merely brushing away the possibility of future dirt.

Joe set about removing from their hiding place other treasures purchased in recent months: six brand-new Western-cut shirts, new slacks (black gabardines and black cottons), new underwear, socks (a half dozen pair, still in their cellophanes), two silk handkerchiefs to be worn at his neck, a silver ring from Juarez, an eight-transistor portable radio that brought in Mexico City without a murmur of static, a new electric razor, four packs of Camels and several of Juicy Fruit chewing gum, toilet articles, a stack of old letters, etc.

During the grooming process, he seldom looked at his total image… He was in some ways like a mother preparing her child to meet some important personage whose judgment will decide the child’s fate.”

Then he took a shower and returned to the room to groom himself for the trip. He shaved with his new electric razor, cleaning it carefully before placing it in the suitcase, splashed his face and armpits and crotch with Florida Water, combed a nickel-sized glob of Brylcream into his brown hair, making it appear almost black, sweetened his mouth with a fresh stick of Juicy Fruit and spat it out, applied some special leather lotion to his new boots, put on a fresh, seven-dollar shirt (black, decorated with white piping, a shirt that fit his lean, broad-shouldered frame almost as close and neat as his own skin), tied a blue handkerchief at his throat, arranged the cuffs of his tight-thighed whipcord trousers in such a way that, with a kind of stylish untidiness, they were half in and half out of those richly gleaming black boots so you could still see the yellow sunbursts at the ankles, and finally he put on a cream-colored leather sport coat so soft and supple it seemed to be alive.

Now Joe would appraise the finished product. During the grooming process, he seldom looked at his total image. He would allow himself to focus only upon that patch of face being covered by the razor at a given moment, or at the portion of the head through which the comb was traveling, and so on. For he didn’t want to wear out his ability to perceive himself as a whole. He was in some ways like a mother preparing her child to meet some important personage whose judgment will decide the child’s fate, and so when all was ready and the time had come to assess the total effect, Joe Buck would actually turn his back on the mirror and walk away from it, roll his shoulders to get the kinks out, take a few deep belly breaths and a couple of quick knee bends, and crack his knuckles. Then he would slouch in a way that he thought attractive and that was his habitual stance anyway – most of his weight on one foot – get hold of a certain image in his mind, probably of some pretty, wide-eyed adoring girl, smile at it with a kind of crooked, indulgent wisdom, light a Camel and stick it into his mouth, and hook one thumb into his low-riding garrison belt. And now, ready for that fresh look at himself, he would swing his eyes back onto the mirror as if some hidden interloper beyond the glass had suddenly called his name: Joe Buck!

On this day of the trip, Joe liked especially what he saw: liked the sweet, dark, dangerous devil he surprised in the dirty mirror of that H tel room. Beyond his own reflection he could see the splendid suitcase lying on the bed, and in his hip pocket he could feel the flat-folded money, two hundred and twenty-four dollars, more than he’d ever at any one time owned before. And he felt most of all the possession of himself, inside his own skin, standing in his own boots, motivator of his own muscles and faculties, possessor of all that beauty and hardness and juice and youngness, box-seat ticket holder to the brilliant big top of his own future, and it was nearly overwhelming to him. Formerly, and not so long ago, there had confronted him always in mirrors a brooding and frightened and lonesome person who was not at all pleased with himself, but he was gone now, put out of the way entirely, while Joe beheld the new. He could not have borne one more scrap of splendor without buckling under the wonder of it, for even as it was he felt that if he savored for one more instant the incredible good fortune of being himself in this time and place and on the move through it, he might easily wreck it all by weeping.

And so he gathered up his possessions and left that H tel for good.

From the novel Midnight Cowboy, courtesy Rosetta Books

James Leo Herlihy was born in 1927 in Detroit, to a working-class family. After serving in World War II, he studied art, literature and music at Black Mountain College in North Carolina. After a professor told Herlihy that he had no future as a writer, he turned his attention to theatre, where he and found acting roles in more than fifty plays. In 1960 he published All Fall Down, which was adapted for film starring Eva Marie Saint, Karl Malden and Warren Beatty. Midnight Cowboy, which followed in 1965, cemented his reputation as a serious writer. Herlihy subsequently retreated from the public eye and turned his attention to teaching creative writing at the City College of New York, the University of Arkansas and the University of Southern California. He died in Los Angeles in 1993 from an overdose of sleeping medication. Midnight Cowboy is published in paperback and ebook by Rosetta Books.

James Leo Herlihy was born in 1927 in Detroit, to a working-class family. After serving in World War II, he studied art, literature and music at Black Mountain College in North Carolina. After a professor told Herlihy that he had no future as a writer, he turned his attention to theatre, where he and found acting roles in more than fifty plays. In 1960 he published All Fall Down, which was adapted for film starring Eva Marie Saint, Karl Malden and Warren Beatty. Midnight Cowboy, which followed in 1965, cemented his reputation as a serious writer. Herlihy subsequently retreated from the public eye and turned his attention to teaching creative writing at the City College of New York, the University of Arkansas and the University of Southern California. He died in Los Angeles in 1993 from an overdose of sleeping medication. Midnight Cowboy is published in paperback and ebook by Rosetta Books.

Read more

Buy at amazon.co.uk

@Rosetta_Books_

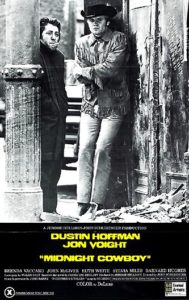

BFI Distribution presents a new 4K restoration of John Schlesinger’s Midnight Cowboy starring Dustin Hoffman and Jon Voight, at selected UK cinemas from Friday 13 September to Wednesday 27 November, marking the 50th anniversary of the film’s first release.

More info

“One of those rare films that you end up thinking about all the time.” Guardian