Lewis and Ernest and Hadley

by Mark LurieLewis scooped a handful of mail from the pile on his desk and riffled through it, his eyes scanning the senders’ names on the envelopes. He recognized some as American bankers, undoubtedly asking him to impress on the French that their war loans must be repaid. And some as French officials, reminding him that the loans had been repaid with the blood of their country’s youth along the Somme and the Marne and the Meuse. And, of course, there were the inquiries from all quarters about whether the reparations scheme, agreed to in the Treaty of Versailles and not yet three years old, was being circumvented, by whom, and in what ways. Then the address on one envelope caught his eye and quickened his pulse. It was a letter from the novelist Sherwood Anderson, whom Lewis had gotten to know while working as a book salesman in Chicago. Sherwood and his wife had visited Lewis in Paris the previous summer. Lewis eagerly sliced open the envelope:

November 28, 1921

My dear Lewis: A friend of mine and a very delightful man, Ernest Hemingway, and his wife are leaving for Paris. They will sail December 8th and go to Hotel Jacob, at least temporarily. Hemingway is a young fellow of extraordinary talent and, I believe, will get somewhere. He has been a quite wonderful newspaper man, but has practically given up newspaper work for the last year. Recently he got an assignment to do European letters for some Toronto newspaper for whom he formerly worked, and this is giving him the opportunity he has wanted, to live in Europe for a time. I have talked to him a great deal about you and have given him your address. I trust you will be on the lookout for him at the Hotel Jacob along about the 20th or 21st of December.

[Ernest’s] wife [Hadley] is charming. They will settle down to live in Paris, and [I] am sure you will find them great playmates. As I understand it, they will not have much money, so that they will probably want to live over in the Latin Quarter. However, Hemingway can himself find quarters after he gets there, and the Hotel Jacob will do temporarily.

What Sherwood’s letter left unsaid was that Hemingway was coming to Paris in the desperate hope that there, at last, he would find a literary voice. The stories he had written – mostly about his exploits as a military ambulance driver melded with the war stories of others – had, so far, been rejected. The Saturday Evening Post had refused them all. And his income, aside from what Hadley’s trust fund brought in, was the small stipend of a features writer for the Toronto Star newspaper.

The person who opened the door surprised Ernest. He pushed the note back into his pocket, unconvinced that this little fellow was the person of consequence that Sherwood had described.”

Three weeks later, Lewis detoured from his usual route to the International Chamber of Commerce, where he held the post of secretary to the US commissioner. Crossing over to the Left Bank of the Seine, he stopped in at the Hotel Jacob, saw that the Hemingways had registered, and left them an invitation to come to his apartment at 24 Quai de Béthune the next day. Ernest wrote to Sherwood Anderson:

Well here we are. And we sit outside the Dome Cafe, opposite the Rotunde that’s being redecorated, warmed up against one of those charcoal braziers and it’s so damned cold outside and the brazier makes it so warm and we drink rum punch, hot, and the rhum enters into us like the Holy Spirit…

We had a note from Louis Galantière this morning and will call on him tomorrow.

On that next evening, Ernest and Hadley set out for the broad promenade that frames the Seine’s southern embankment and whose name changes with each passing bridge: the Quai Saint Michel… the Quai de Montebello… the Quai de la Tournelle… their hedgerow of green canvas and wood stalls filled with paintings, stamps, and rare books: things that the devastation of the Great War had made plentiful and that the vendors, weary after their day in the cold, were eager and reluctant to sell. Ernest and Hadley walked across the Pont de la Tournelle to the Île Saint Louis, turned right, counted down the address numbers of the seventeenth-century five-story stone residences, entered number 24 and knocked. As the door opened, Ernest reached into his pocket to retrieve a letter of introduction – one of several such letters that Sherwood had addressed to Lewis and to Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound, Sylvia Beach, and others.

The person who opened the door surprised Ernest. He had the appearance of a midlevel bookkeeper: thin, about five foot five and 130 pounds, black hair combed smooth, a carefully trimmed square moustache and rimless glasses. Ernest pushed the note back into his pocket, unconvinced that this little fellow was the person of consequence that Sherwood had described. Lewis, observing Hemingway’s indecision, deduced what was going on. He would bide his time.

Over the course of the evening, Ernest grew resentful of this little man… He told Lewis that he had two pairs of regulation boxing gloves in his hotel room and that the two of them should do some friendly sparring after dinner.”

That Friday evening’s plan was to reconnoiter the Left Bank for a suitable apartment. The trio walked through the fifth and sixth arrondissements of Paris, referred to as the Latin Quarter, but nothing Hemingway saw satisfied his wants and self-imposed budget. They ended up at the Café Michaud, then an epicurean restaurant, where Lewis bought the newlyweds dinner and entertained them with his repertoire of cultural insights. The conversation eventually got around to Ernest’s passion – boxing – and his description of how, on the voyage over, he had fought and beaten another American in a three-round exhibition match. Lewis’s experience with the sport had been a few lessons at a California Army camp, Camp Kearny, two years earlier. His instructor, George Blake, a former professional boxer and now a popular referee, was a man whose self-effacing nature and homespun way of speaking had made a firm impression upon Lewis, one that he enjoyed imitating:

“Well, Lewis” he says, “let’s go put on the feed bag.”… “Can he hit? Why he couldn’t hit water if he fell out of the boat.” In telling a smutty story: “so then he went upstairs to take a ride in the midnight handicap…”

Hadley listened avidly but, over the course of the evening, Ernest grew resentful of this little man who was so damned charming. He told Lewis that he had two pairs of regulation boxing gloves in his hotel room and that the two of them should do some friendly sparring after dinner. Lewis, although probably alarmed by the invitation, played the good sport, or maybe felt obliged not to appear a coward. The Hotel Jacob was just a few doors down from the restaurant and it was Friday night. No ready excuse was at hand.

The three went to the Hemingways’ room, Ernest and Lewis laced-up, and Hadley, serving as ringmaster, called out the bell for the first round. The two men stepped forward. At six feet tall, Ernest loomed over Lewis. The men circled, tapping gloves here and there, tentatively parrying, weaving, skipping, and dodging, in a display of form over substance until Hadley called the end of the round. Lewis retired to his corner, unlaced one glove, and put on his glasses, unaware that Ernest was approaching. As Lewis turned, he offered a clear target for Ernest’s sucker punch that caught him squarely on the face, breaking his glasses.

With that, the incipient friendship might have ended. That it did not was attributable, on Lewis’s part, to his neither wanting to disappoint his friend Sherwood Anderson nor to have people think that he was the sort who couldn’t “take it.” Or perhaps he thought he had it coming. On Ernest’s part, he could not afford to burn a bridge before he had crossed it. Despite that rocky start, over the coming five years, Lewis and Ernest formed a friendship that was sometimes enjoyable, always intense, and often turbulent for reasons that had nothing to do with the mutual respect and affection they came to share.

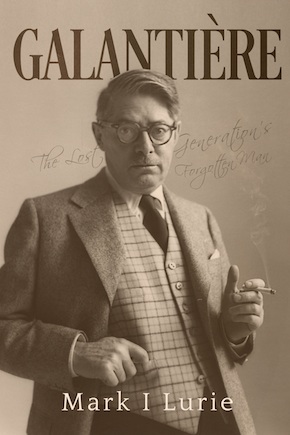

From Galantière: The Lost Generation’s Forgotten Man (Overlook Press, £25)

Mark Lurie is a labour arbitrator and mediator, and editor–in-chief of print and online journals for the National Academy of Arbitrators. After learning that his father’s cousin Lewis Galantière had been a figure in twentieth-century American literature, Mark embarked on a four-year investigation of Galantière’s work, combing through thousands of pages of correspondence, photographs and government documents. Mark’s debut book Galantière: The Lost Generation’s Forgotten Man is the result, out now from Overlook Press.

Mark Lurie is a labour arbitrator and mediator, and editor–in-chief of print and online journals for the National Academy of Arbitrators. After learning that his father’s cousin Lewis Galantière had been a figure in twentieth-century American literature, Mark embarked on a four-year investigation of Galantière’s work, combing through thousands of pages of correspondence, photographs and government documents. Mark’s debut book Galantière: The Lost Generation’s Forgotten Man is the result, out now from Overlook Press.

Read more

mark-lurie.com

“Galantière could have sprung full-grown from a novel by Saul Bellow:

a fantastical creature whose most successful fiction was himself.”

Rosanna Warren, University of Chicago