Louise Candlish: Location, location

by Karin Salvalaggio

“Twisty, warped, credible. Brilliantly plotted and compelling.” Sarah Vaughan

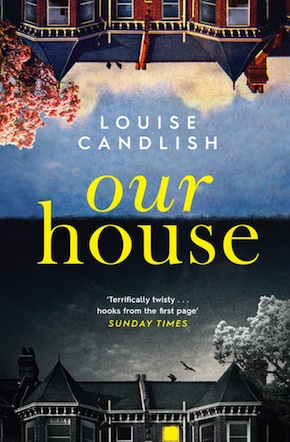

Louise Candlish’s twelfth novel Our House is an outstanding thriller that has been receiving high praise. I had the good fortune to meet Louise earlier this year in Bristol where we were both attending Crimefest. A few weeks later I received a copy of Our House in the post. Set in a leafy London suburb very much like my own, it is a novel I could relate to on an uncomfortable number of levels. The book opens as Fiona Lawson discovers a family of strangers moving into her home; and that her husband Bram and their children are missing. The narrative then splits, moving forward in real time using both Fiona and Bram’s viewpoints while simultaneously working forward from an earlier date using excerpts from Bram’s suicide note and the transcript from a popular true crime podcast called The Victim that Fiona is recording. The reader is able to piece together what happened through these different sources, all of which are distinct.

KS: What led you to this particular narrative structure, and what did you find were its benefits and pitfalls? Could you also comment on the confessional nature of the suicide note in contrast to the podcast, which is by its very nature a platform where an individual can and will put their own spin on events?

LC: It’s a complex structure and keeping it straight was like octopus-wrangling – if there is such a thing! I hadn’t tried a narrative technique like this before, so I was learning on the job. I love reading novels (and watching TV) that is constructed as a puzzle and so I wanted to devise one myself – to tease and challenge the reader in a rewarding way. The main difficulty was in the ordering of the scenes. I spent a lot of time playing with the four strands – Fi’s podcast, Bram’s account, plus their respective present-day action – and getting the juxtaposition right. A lot of material was cut, too.

There is a great deal in Our House that rings true. Alder Rise is a fictitious South London neighbourhood very much like Bedford Park, a community in West London where I’ve lived for the past 23 years. You could have been writing about my own experiences as a homeowner, down to the unfortunate turn when my marriage disintegrated. Like Fiona, I was adamant about keeping the house not just for the children’s sake, but my own. The house is a part of who I am and I still live here even though I should have sold it years ago. I remember my ex-husband suggesting we set it up as a ‘bird’s nest’, although he didn’t call it that at the time. We would share the house and another residence, taking turns being on our own with the children. I didn’t think it was a good idea. We were barely on speaking terms. Being reminded of each other’s existence on a daily basis wouldn’t have gone down well. At a time when it was important for us to move on, it was a choice that would have left us standing still. Fiona doesn’t give her situation much thought because the bird’s nest is the only solution that would allow her to keep the house. In her eyes, the thought of losing her home is more upsetting than losing her husband. How did you come to use the bird’s nest idea in your novel? Was it something you read about in the papers, or did you come across it personally? As far I can tell, it’s still very rare here in the UK but growing more popular in the States.

I knew at once I’d found the perfect facilitation for the crime. There is no way a spouse can sell the family home if the innocent party is living there full-time.”

That’s so interesting that you considered bird’s nest custody – and I suspect you were right not to do it, because it requires Gwyneth Paltrow-Chris Martin levels of ongoing patience and cordial regard! Some couples really need a clean split with no reminders, but when it works I think it’s brilliant for the kids. Families have been doing it informally for decades, but now it has a label. I also understand it to be a US concept. I read about it in the Telegraph at exactly the time I was plotting Our House and I knew at once I’d found the perfect facilitation for the crime. There is no way a spouse can sell the family home if the innocent party is living there full-time. Bird’s nest arrangements made it just about doable.

Rachel Cusk’s Arlington Park is set in a fictitious London neighbourhood similar to Alder Rise and Bedford Park. It is a scathing social commentary that left me feeling cold. The women Cusk describes bear no resemblance to people who live in such neighbourhoods. They are, in my humble opinion, unrecognisable caricatures. Your observations are no less damning, but it is the characters themselves who grow to understand and acknowledge their own failings. The result is a deeply sympathetic portrayal of human frailty that feels genuine.

Did you have a particular London neighbourhood in mind when you came up with the setting of Alder Rise, and did you draw from your own experiences?

Funny you should mention Arlington Park because I am a huge Cusk fan and absolutely love that book! You’re right, though, it is very, very cold, the perspective of a true outsider, whereas in Our House Fi is an insider. She fits in, she belongs, and that’s partly why it’s so grievous for her to be torn away from it. Alder Rise is a composite of neighbourhoods in South London. It’s a bit like Herne Hill, where I live, or East Dulwich or Crystal Palace.

In Status Anxiety, Alain de Botton writes: “Blessed with riches and possibilities far beyond anything imagined by ancestors who tilled the unpredictable soil of medieval Europe, modern populations have nonetheless shown a remarkable capacity to feel that neither who they are nor what they have is quite enough.”

Fiona’s self-worth is so tied up in her home’s value that she’s lost all sense of proportion. In 1996, when London was just coming out of a recession, the average home cost £79,000. Today prices have jumped over 600 per cent to an average £488,908. Fiona seems to think the residents of Alder Rise are the chosen ones when in reality they are simply the lucky ones. Like many Londoners, they couldn’t afford to buy their houses at the prices they are today. Yet they always want more. They add value to their homes at the expense of family holidays and weekends away with their increasingly estranged spouses. They balance jobs and children, rarely having time for themselves. Instead of relaxing at the weekends, they fill every minute with activities that are meant to amplify their status. It makes you wonder how things would have panned out for Bram and Fiona had they sold up, downsized and settled for less. Two million pounds may not go a long way in London, but it could keep you happy in South Wales for a lifetime.

There are times when Our House reads like a suburban cautionary tale about the perils of greed. Was this your intention? Why do you suppose such communities are perfect settings for crime novels?

Again, you’ve hit the nail on the head: this book was conceived as a cautionary tale, pure and simple. There is a housing crisis in the UK and society has rarely been so divided between the haves and have-nots. Those of us lucky enough to own property can’t help being obsessed with our good fortune. The media feed our obsession. Not to simplify the issue, I do think age is a factor. Fi and her friends are in their early forties, which I see as being the optimum age for accruing material wealth. I’m a bit older than that and I’ve felt the urge fade. Now I want to get rid of stuff, not accumulate it. To answer your question (finally), I think such wealthy communities are perfect for crime novels because the residents have so much to lose. So much. The critic Jake Kerridge called this book “Schadenfreude for Generation Rent” and I think that’s a great description.

I’ve never, ever set out to create a likeable character, I wouldn’t know how.”

Bram’s point of view is a welcome counterpoint to Fiona’s. He’s not grown up in a middle-class environment, so is an outsider. He plays the role of the suburban dad and husband well enough to pass, but the strain of keeping up appearances is quietly tearing him apart. I first felt Bram was too whiny and irresponsible to be a sympathetic character. A second reading changed my mind: he was fallible but not without merit, and once you understand his history you can’t help but feel some sympathy for him.

Were you conscious of a need to balance your two principal characters’ points of view? Was giving Bram the last word always your intention?

It was quite a task to balance their two voices, because long-term married couples have shared references, humour, tone and so on, so it would have been odd to make them sound like separate species. There are differences, though, in class and in mental health. The contrasting forms helped: Bram is confessional, he’s giving a detailed account and you can pretty much trust him, whereas Fi has chosen to give a public interview and anyone doing this is, by definition, limited either to what they’re asked or what they want to say. I didn’t plan for Bram to have the last word, which readers are calling a twist. It happened naturally.

I love inserting a bit of symbolism into my writing as it adds subtle layers of interest. I may have this wrong, but does the number three have particular significance in Our House? Fiona’s marriage comes to an end because of a third party, three points are added to Bram’s license each time he’s caught speeding, and their house is located on Trinity Avenue. Then there are the three perfect hydrangea blooms that Fi is given in the wake of her marital breakdown. Fi observes that the grouping of three is a satisfying arrangement as it follows the rule of asymmetry adhered to in home decoration. Fi is supposedly grieving the end of her marriage but is instead focusing on rules of asymmetry and the fact that the flowers would have been bought from an expensive florist. Did you purposefully set out to make the number three significant or was it accidental?

This is accidental, but it could be subconscious because I am in a family of three myself and often think in terms of the Three Musketeers! There’s something both strong and fragile about a trio.

Hydrangeas are said to represent boastfulness and vanity, possibly because of their large showy blooms, and according to the rules of feng shui, magnolia trees represent pleasure when planted in the front garden and the slow but sure acquisition of wealth when planted in the rear, which makes me think the tree was in the wrong spot.

That’s fascinating! I do love hydrangeas…

Fiona’s self-control borders on pathological. There is no slow release of tension, no hint of righteous anger. Bram is practically begging to be punished, but Fiona lets him get away with one infraction after another by simply glossing over the many issues they’re having. Without boundaries, he grows increasingly reckless. Fiona tells friends who are puzzled by her decision to throw Bram a lifeline that “not every story has to be about revenge”. She acts holier than thou, but we soon learn that she has no claim to the moral high ground.

Fiona isn’t a particularly likeable character. What do you think it is about her that makes readers want to see her story through to its devastating conclusion?

I’ve never, ever set out to create a likeable character, I wouldn’t know how. I think the thing to remember about Fi is that there is a certain artifice to her narrative – she is being interviewed and has had the benefit of preparation. She likely doesn’t want to share the moments when she felt rage or despair in her marriage. There are a few lapses, though, when she allows emotion to get the better of her, like when she’s asked if she’s a control freak and she has a little rant. I knew from the outset that readers might find her annoying, which was partly why I included the tweets. Some tweets point out how entitled she is, others how clueless, but one or two offer sympathy.

Fiona’s behaviour only strays outside acceptable norms when she is sexually humiliated. She appears to be confident at first, but it’s soon clear that she suffers from low self-esteem. She refers to herself as a middle-aged crone even though she’s only 43. Bram describes her as having curves that draw the male gaze but are disavowed by their owner as excessive. It is only after she is sexually humiliated in one of the final scenes that she truly loses her temper:

Her anger returns in a torrent.

You’re obviously no use to anyone.

A younger, sexier model…

What kind of dumb fuck…?

What do you suppose it is that’s missing in these women’s lives that leave them so vulnerable to feelings of rejection?

I think it’s fair to say that most women want to feel desirable, and history tells us over and over again that sexual humiliation or rejection can lead to regrettable acts of retaliation. What’s missing for some of the women in the book is perspective. They’re in that frightening no man’s land between youthful desirability and middle-aged wisdom. To the outside world, they have everything, but no one ever has everything. It’s only ever an illusion.

Louise Candlish’s previous novels include The Sudden Departure of the Frasers, The Swimming Pool and the international bestseller Since I Don’t Have You. She studied English at University College London and worked as an advertising copywriter and art book editor before writing fiction. She lives in South London with her husband and teenage daughter. Our House is out now in paperback and eBook from Simon & Schuster.

Louise Candlish’s previous novels include The Sudden Departure of the Frasers, The Swimming Pool and the international bestseller Since I Don’t Have You. She studied English at University College London and worked as an advertising copywriter and art book editor before writing fiction. She lives in South London with her husband and teenage daughter. Our House is out now in paperback and eBook from Simon & Schuster.

Read more

@louise_candlish

louisecandlish.com

Author portrait © Jonny Ring

Karin Salvalaggio is the author of the Macy Greeley crime novels Bone Dust White, Burnt River, Walleye Junction and Silent Rain and a contributing editor at Bookanista. Her fiction to date is set in towns that border the Montana wilderness, a uniquely spectacular landscape she fell in love with as a child. Her proudly independent characters inhabit stories about the American dream gone wrong. She is currently working on the final edits of a psychological thriller set closer to home in West London, where she has lived since 1994. The characters may be hemmed in by glass and steel, but the stories they tell are just as compelling.

karinsalvalaggio.com

@KarinSalvala