Love in Ramallah

by Ibrahim Nasrallah

“A glimpse into the inner lives of those in the city of Ramallah on their own terms… imbued with hope and humour.” Cosmopolitan

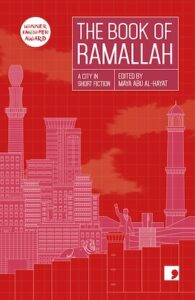

Unlike most other Palestinian cities, Ramallah is a relatively new town, a de facto capital of the West Bank allowed to thrive after the Oslo Peace Accords, but just as quickly hemmed in and suffocated by the Occupation as the Accords have failed. Perched along the top of a mountainous ridge, it plays host to many contradictions: traditional Palestinian architecture jostling against aspirational developments and cultural initiatives, a thriving nightlife in one district, with much more conservative, religious attitudes in the next. Most striking however is the quiet dignity, resilience and humour of its people; citizens who take their lives into their hands every time they travel from one place to the next, who continue to live through countless sieges, and yet still find the time and resourcefulness to create. The Book of Ramallah, edited by Maya Abu Al-Hayat for the celebrated ‘Reading the City’ series from Comma Press, collects together ten tales by contemporary writers that offer a vibrant insight into the soul of the city. Ibrahim Nasrallah’s ‘Love in Ramallah’ is the opening story.

1

Warda knocked at Umm Walid’s door and the woman emerged moments later.1

‘Ahlan wa sahlan.2 What can I do for you, my child?’

‘I heard there is a young man, a bachelor in your house,’3 said Warda.

‘Well, he’s not exactly young,’ Umm Walid said with bemusement, adding, ‘What do you want from him?’

‘Just so there’s no confusion, could I check, is he called… Yasseen?’

‘Yes he is,’ Umm Walid nodded.

‘Well that means he’s young!’ Warda exclaimed.

‘But you really should meet him before proposing to marry him, don’t you think?!’

‘No, it really isn’t necessary! Is he here?’

Umm Walid shook her head.

‘If he is actually here but is just hiding then tell him that a girl will picket your house until he agrees to marry her!’

‘Is that your final word then?’ asked Umm Walid.

‘Final!’

‘If you were enquiring about anyone other than Yasseen I would have said you were crazy.’

Warda smiled: ‘Al-hamdulillah, that puts my heart at ease.’

—

When Umm Walid related the tale to Yasseen he couldn’t stop laughing.

‘It’s a good sign don’t you think?’ she asked.

‘I wonder how she found our house.’

‘She said she learnt of you from the play about your life and your years in prison, and that she felt the genuine article would be even better. So she followed her heart here.’

After a long silence he asked, ‘But, what did you think of her?’

‘Honestly?’

‘Of course!’

An even longer silence elapsed and then a smile spread and filled her face, and she said, ‘To tell you the truth, I liked her.’

So he said, ‘I wanted to say the same thing, even before I’ve met her!’

2

‘By Allah, your age is showing, Na’eem,’ Yasseen said.

‘We’ve all aged,’ replied Na’eem. ‘You don’t even play football with me anymore! Do you remember how you used to take me and the other local kids out to play every week? And now you’re back to take their children out.’ Then he added: ‘What about your kids? Isn’t it time for you to get married and have some?’

‘Me? Nah, our people don’t need one more widow and another set of orphans. There is enough suffering here! You’re the one that should get married.’

‘No, I’ve missed it, my friend, and I’m not talking about the train.’ Then he laughed. ‘Don’t take me seriously.’

‘If you had said anything else, I would’ve said prison had changed you,’ Na’eem replied.

Na’eem knew all about checkpoints. He knew that at this time of day the soldiers like to toy with the passengers for their own entertainment, to treat them as their playthings.”

The bus to Ramallah had to stop at an Israeli checkpoint between two hills, a place called Uyoun al-Haramiya.4 There had never been a day when soldiers hadn’t been stationed at this spot. First it was the British soldiers; after them the Jordanian soldiers and now here we have the Israeli soldiers. Yasseen knew all this.

‘One day we will have a checkpoint here,’ Na’eem said.

‘Can you see how grand our ambitions are now?’ Yasseen retorted.

They ordered the passengers off the bus. Then a soldier boarded it and walked the length of the aisle until he reached the long back seat. Then, from inside he looked back out at the faces of the passengers lined up on the tarmac looking for any expression other than indifference.

The soldier got off the bus and circled around the passengers, stopping beside an attractive young girl to stare at her. He walked a few steps then stopped again. Turning, he signalled to three other soldiers, observing the scene from 15 metres away, to come closer.

As they approached he walked to the end of the line of passengers and stopped by Yasseen and Na’eem, signalling to Na’eem to step forward.

Na’eem knew all about checkpoints. He knew every one, from his earliest days they had been in his face, waiting for him. From experience, he knew that at this time of day the soldiers like to toy with the passengers for their own entertainment, to treat them as their playthings.

The heat at 4.30 in the afternoon was enough to ignite the air between the two hills. Yasseen took a look at the line of cars piling up behind the bus. A person needed no superpowers to hear the silent curses emanating from their eyes, the body language that betrayed a frustration with everything around them.

‘COME!’ the soldier barked at Na’eem who hadn’t moved.

The soldier stopped directly in front of the attractive young girl, and there behind him now stood Na’eem. The soldier turned, looked at Na’eem, then looked back to the young girl. ‘Do you want the bus to pass?’ he asked Na’eem. Na’eem nodded in affirmation.

‘If you want the bus to pass, you have to kiss her!’ the soldier said, pointing at the girl.

A glimmer lit up the soldiers’ eyes. They liked this game, it enthused them. The passengers by contrast looked at one another bemused. As for the young girl, the whole thing was like a shock to her.

A car horn behind the bus broke the silence for a moment.

‘Who’s that khmaar5 beeping?’ yelled the game master, heading back towards the car. The driver tried in vain to convince him that the horn had gone off by accident, but the soldier insisted that the car leave the long queue, turn around and go back to where it came, Nablus.

‘If you want to sleep the night here, then stay, or you can go back to Nablus. But there is no Ramallah for you today, understood!?’

A few minutes later the car and its passengers were heading away from the checkpoint, back to the other checkpoint they had just left behind, the three kids looking out of the back window trying to figure out what had just happened.

The game master turned back to Na’eem and said, ‘Do you think it’s over? It is up to you. You Palestinians are always talking about making independent decisions. Well, if you want the bus to pass and for the cars behind it to pass, then do as I say.’

The young girl poked her head above the surface. Until this point she’d been submerged in a lake of shame. With eyes pregnant with tears, she looked at Na’eem who looked as if he were in an even bigger lake of his own.

In front of the checkpoint, the soldiers were giggling to themselves. Rummaging for change in their pockets and passing it around, they began placing bets on whether he would kiss her or not.”

Admittedly, for all his knowledge of checkpoints, he’d never contemplated a scenario like this. He looked to his friend, Yasseen, finding him lost as if in a daze. Just before Na’eem turned back to face the soldier, Yasseen locked eyes with him for a moment. Then the soldier pressed him: ‘Have you decided?’

‘I won’t do what you ask.’

‘I told you, you’re free khabibi,6 don’t kiss if you don’t wanna kiss. But if you and the others do want to pass through here, then kiss her.’ Then, as he walked away, he added: ‘Don’t move from where you are. Stay put.’

In front of the checkpoint, the soldiers were giggling to themselves. Rummaging for change in their pockets and passing it around, they began placing bets on whether he would kiss her or not. He will kiss her, the game master said as he pulled some cash from his pocket and flung it on the sandbags. The sun was beginning to set and the passengers felt like they were suspended in time. The soldier approached Na’eem again and asked, ‘Haven’t you decided yet?’

‘I won’t do as you ask.’

And so the rifle butt struck his thigh. Everyone heard the thud on his femur before he fell to the ground, only for the soldier’s jackboot to follow up, landing in his stomach.

‘We’re busy here, I told you if you kiss her you all pass. If not you sleep here.’

‘I won’t do as you ask.’

The soldiers protested this foul play by the game master; his use of violence could change the outcome of the bet. But he was deaf to their complaints.

Another blow came. Na’eem tried to dodge it but there was no escape; blood spurted from his forehead. The soldier walked away. Things felt like they were about to explode. The lined-up passengers were getting restless as they watched the scene without being able to move. Passengers from several of the cars and buses had disembarked on either side of the road. Now the guns turned to them; the soldiers ordered them back to their cars.

In a turn that nobody saw coming the young girl bent down by the man on the ground in front of her, took his hand and whispered, ‘Kiss me, I beg you!’

Na’eem looked up at the passengers again; they were staring at the ground trying to not be there.

He kissed her on her right cheek. As his lips met her face several of the soldiers whooped, as if they were cheering for a winning goal scored by their team, while others grumbled in disapproval.

—

As the bus rolled past the checkpoint, the passengers’ eyes reflected a mixture of shame, oppression, anger and disapproval. They stared brokenly at the floor; silence was the new passenger they had taken on.

The young girl raised her head, while all the other heads were lowered. She looked at the young man who, as if he could feel her gaze, raised his own head and looked back at her. And so it was till the last stop.

The passengers left their seats, followed by Yasseen. The only two people left on the bus were a young man and a young girl.

3

Umm Walid always knew when her nephew had arrived when she found a bouquet of roses on the windowsill.

At first, she would admonish him: ‘Why the roses? They must have cost you a fortune!’ But then she started getting used to them. She would miss them whenever Yasseen was late bringing in a new bouquet for her. The roses would dry out but she would keep them and keep waiting, and waiting.

‘You know, I now wait for the roses like the trees await the rain. My heart sings when I see them!’

‘I promise you, the vase will never be empty of roses.’

‘But doesn’t it bother you to bring them all the way from Ramallah?’

‘No, but the glances I get from the passengers do. It confuses me, Umm Walid, that someone can carry a sack of molokhia7 or onions from Jenin to Rafah8 without anyone raising an eyebrow, but when I bring a bouquet of roses, everyone starts eyeing me up as if I am in my birthday suit.’

‘Does it embarrass you?’

‘No, it never embarrasses me, but it irks me that roses are so alien. The moment we leave Ramallah, silence takes over, and it’s almost as if I can hear their theories and questions: “The roses are for his wife,” one thinks, while another: “No one gives his wife roses these days. He must be going to a wedding, or a birthday” And a third “Could it be this old fox has forgotten he’s no longer a teenager and fallen in love?!”’

‘Oh Yasseen, may Allah have mercy on you. People are kind-hearted and don’t think like that!’

‘People – not just here, but in many places – find it easier to curse than be kind. Have you ever seen a plane dropping roses on a city?’

‘Of course not.’

‘But you’ve seen a plane dropping bombs?’

‘Often.’

‘You see! The world is crazy. How about you! How many times have you told Abu Walid that you love him, in public?’

‘Goodness! In front of people? I’ve never even told him I love him in private!’

‘Ha! But if you had, why wouldn’t you say it in public?’

‘Do you want them to say I am crazy?’

‘You see! This is what I’m trying to say. Our shame of beautiful things surpasses our shame of the truly shameful. Either way, I will keep on bringing you roses, tormenting those who find it strange that I am carrying them all the way from Ramallah.’

‘Do you mean there are people who don’t find it strange?’

‘Sometimes. Once, after staring at me and the roses for a while, a woman sighed then said to me: “I envy her, she’s lucky.’’ I asked her, “Who do you mean ‘she’?” So, she said, “The one you’re taking the roses for.” So, I told her, “No, I am the lucky one, to have her.” To which she said: “Then she’s doubly lucky, to have you and to have your roses.”

Then Umm Walid looked at him: ‘Why don’t you settle down, Yasseen?’

‘Believe me, if I settled down I would go crazy.’

She swept her gaze swiftly among them until she settled at the far edge of the yard where Abu Walid sat, along with a group of men who were consumed in a conversation so familiar to her that she could probably guess every word.”

Under the midday sun glinting through clouds, in front of the two almond trees that shaded the lower yard of her house now destroyed, beneath a flock of house sparrows hovering above the damaged power lines watching cautiously for the yard to be clear of kids, Umm Walid gazed into the distance. She looked past the clutch of children playing in the dirt yard; there were less of them today than usual. Looking up at the towering sky, she saw three kites soaring. Then she turned her eyes to her neighbour’s window, the pane punched out by a missile that went on to rip through the kids behind it, all were waiting for their mother to make them breakfast before going to school.

Umm Walid went back to looking into the distance. She could see the children playing. Today they seemed to be playing with the kind of joy they felt the very first time they played. She didn’t know what number they needed to make two teams to chase a ball around, so she carried on staring into the distance…

The children’s cries brought her back to earth. She swept her gaze swiftly among them until she settled at the far edge of the yard where Abu Walid sat, along with a group of men who were consumed in a conversation so familiar to her that she could probably guess every word.

Ibrahim Nasrallah’s The Second War of the Dog, winner of the 2018 International Prize for Arabic Fiction (IPAF)

150, maybe 200 metres was all that separated them, no more.

A noise she knew well took swung her attention to the end of the road. An army patrol, four jeeps roaring up the road towards her, choking the alley with their black smoke. Here they are again, occupying everything.

Yasseen’s face swung into her line of sight, then disappeared.

The clamour of the jeeps brought her back to their street. They were now next to her house, parked close to its northern side.

But the children didn’t stop playing. They carried on as if the place had never seen a soldier. There, above the wires the caution that had set into the wings of the sparrows was noticeable.

Umm Walid returned her gaze to the far side of the yard. The men had stopped chatting as they sensed something was happening on the other side of the wall, they knew nothing of it but were slightly reassured that the children were still playing.

She saw Abu Walid waving at her from afar and waved back. The soldiers noticed their gestures. Yasseen’s face passed by again, but this time it didn’t disappear. She saw him heading down the stairs towards the lower yard and for a moment, she envisioned the yard as it always had been, green and well kept.

She could hear her voice flowing through her body like a river, rising from the depths of her heart, filling her lungs as she called, ‘Abu Walid!’

From the other side of the yard, came his voice, as if he’d been waiting for her call for a long time: ‘What is it?’

‘I love you, Abu Walid. I love you!’

The soldiers watched this old woman calling to her man before their eyes switched to the other side to see him say, ‘What?’

‘I love you,’ she said again.

Abu Walid shook his head. He squinted a little but his eyes shone with an unusual glimmer as he read the faces of his companions.

He lifted his head and, for a moment, it seemed as if the children had stopped playing, and the sparrows didn’t know which way to fly.

As for the soldiers, they were holding their breath.

Abu Walid realised that the whole world had stopped and was waiting for him. He looked to the far side of the yard, where the woman, proud and tall like a pine, was waiting and he called:

‘I love you, Umm Walid!’

‘What?’ she responded, even though she’d heard it loud and clear the first time.

‘I love you!’

And everything settled down.

He observed the silence that his voice had created in the space. ‘She got the message, loud and clear,’ he whispered to himself with a quiet joy, as he returned to his seat. At the same time, the patrol leader shook his head in confusion: ‘An old man, an old woman, shouting “I love you” at each other. Crazy fucking Palestinians.’

As if the pine tree within her suddenly grew higher and higher, she found herself feeling taller than any other day and, casting a compassionate eye to the other side of the yard, watched as the patrol disappeared.

Translated by Mohamed Ghalaieny. From The Book of Ramallah (Comma Press, £9.99)

1 The prefixes ‘Umm’ and ‘Abu’, mean ‘Mother of’ and ‘Father of’, respectively, usually followed by the name of their eldest son.

2 Welcome, but in a very emphatic way, short for ‘you are among us as family members and your stay with us is never a burden’.

3 This is a reference of the social custom where the mothers of unmarried men are known to go enquiring to the families of single young women; only here it is reversed.

4 An Israeli military checkpoint in Wadi al-Haramiya, the valley of the thieves. Uyoun translates as wells or springs.

5 The Arabic word for donkey is hmaar, but Israelis mispronounce the letter h as kh, as in ‘loch’.

6 Habibi, with added kh sound similar to previous footnote, literally means my love but in this context it is similar to the British English usage of ‘mate’.

7 A leafy plant of the nutritious Corchorus olitorius species, known in English as jute mallow and found commonly across the Levant, Egypt and part of Cyprus, used in making a dark green, soup-like dish.

8 Jenin is the northernmost city of the West Bank, and Rafah is in the far south of the Gaza Strip, so saying ‘from Jenin to Rafah’ is like saying from Land’s End to John O’Groats, with the added irony that this journey is not even possible because of Israeli restrictions on movement.

Ibrahim Nasrallah was born in 1954 to Palestinian parents who were evicted from their land in Palestine in 1948. He spent his childhood and youth in a refugee camp in Jordan, and began his career as a teacher in Saudi Arabia. After returning to Amman, he worked in the media and cultural sector until 2006. He has published 15 poetry collections, 21 novels and several other books. In 1985, he started writing the Palestinian Comedy covering 250 years of modern Palestinian history in a series of independent novels. His works have been translated into English, Italian, Danish, Turkish, and Persian. Three of his novels have been shortlisted or longlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction (IPAF) – sometimes referred to as the ‘Arabic Booker’ – and in 2018 he won it with his futuristic novel The Second War of the Dog. In 2012 he won the inaugural Jerusalem Award for Culture and Creativity, and his novel Prairies of Fever was chosen by the Guardian one of the ten most important novels written about the Arab world.

Ibrahim Nasrallah was born in 1954 to Palestinian parents who were evicted from their land in Palestine in 1948. He spent his childhood and youth in a refugee camp in Jordan, and began his career as a teacher in Saudi Arabia. After returning to Amman, he worked in the media and cultural sector until 2006. He has published 15 poetry collections, 21 novels and several other books. In 1985, he started writing the Palestinian Comedy covering 250 years of modern Palestinian history in a series of independent novels. His works have been translated into English, Italian, Danish, Turkish, and Persian. Three of his novels have been shortlisted or longlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction (IPAF) – sometimes referred to as the ‘Arabic Booker’ – and in 2018 he won it with his futuristic novel The Second War of the Dog. In 2012 he won the inaugural Jerusalem Award for Culture and Creativity, and his novel Prairies of Fever was chosen by the Guardian one of the ten most important novels written about the Arab world.

Mohamed Ghalaieny worked for two years as reporter for New York-based Free Speech Radio News in Gaza and as a presenter on Palestine Satellite Channel, conducting and translating live interviews and reports, and whilst in Gaza has volunteered regularly as a translator for the Union of Health and Work Committees. He was a contributing translator to The Book of Khartoum, and Palestine + 100 (Comma Press, 2016 and 2019) and currently works in the field of air quality in the UK.

Maya Abu Al-Hayat is a Beirut-born Palestinian novelist and poet living in Jerusalem. She has published two poetry books, numerous children’s stories and three novels, including her latest No One Knows His Blood Type(Dar Al-Adab, 2013). She is the director of the Palestine Writing Workshop, an institution that seeks to encourage reading in Palestinian communities through creative writing projects and storytelling with children and teachers. She contributed to and wrote a foreword for A Bird is Not a Stone: An Anthology of Contemporary Palestinian Poetry. The Book of Ramallah is published in paperback and eBook by Comma Press.

Read more

@commapress