With love and squalor

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“As for Naples, today I feel drawn above all by Anna Maria Ortese.” Elena Ferrante

Anna Maria Ortese’s Evening Descends Upon the Hills is a book that, Atlas-like, seems to bear on its shoulders the weight of the most overwhelming human sorrow – but also the burden of humanity’s “small, wretched acts of violence, an abyss of voices and events, tiny terrible gestures”, the unspeakable social stains and realities to which Ortese gives voice and discourse, and that Elena Ferrante said gave her writing its sense of direction.

Evening Descends Upon the Hills is a protean collection of short stories, reportage pieces and very intimate cameos of Naples’ “pure Marxist” intelligentsia. Each section is ineluctably and inextricably linked to the others, fiction being the catalyst for realities one cannot otherwise encompass or confront, enunciate or internalise, while reality provides the ultimate reason to be in a world that seems to forbid and abort all existence.

In the short stories, Ortese harkens back to 19th-century realism and naturalism for her models: Gorky, Zola, Dickens, become invested with mid-20th-century grit, malaise and world experience, with the sense of a very different audience. Not yet Moravia, Montale, or Camus, but very near. The language is vernacular, dialectic and idiomatically Neapolitan, juxtaposed to what the characters (working class, invisible, with the inevitable omnipresence of what Ortese presents as depravity and despair) call “proper Italian”, which they cannot understand. The world made by God is equally contrasted to the world made by and lived in by man: human neighbourhoods and dwellings are like anthills, “so many holes, so many ants. And around them, almost invisible in the great light, the world made by God, with the wind, the sun, and out there the purifying sea, so vast…” Yet the sea washes against but does not cleanse or purify Ortese’s homeland, a lament and tragedy, an almost existential rebuke echoed in the original Italian title Il mare non bagna Napoli.

Existence is almost always positioned between the irreconcilable extremes of dejected resignation and impossible/illusory happiness, a no man’s land.”

Children are both heartrending angels, victims of physical and social injustices or plain abuse, but also ignoble savages, whose cruelty Ortese seems to suggest reflects a more primordial truth and eschatology. Women throughout have masculine traits and characters, are “horsey” at best, with “perfect, unchangeable ugliness”. They are grotesque, monstrous or phantom-like – “she was only an enormous flea” or “I sat… next to a woman without a nose, who had an enormous plant in her lap.” An exceptional few are angels in the house, or self-abnegating social reformers, engulfed in the darkness of the world to which they seek to bring some light. Existence is almost always positioned between the irreconcilable extremes of dejected resignation and impossible/illusory happiness, a no man’s land demanding a “rigid mechanism, the old control, all the defences of a race forced to greater and greater sacrifice because there would be hell to pay if they weren’t made.”

Interiors and exteriors have a surreal palpability and intensity, Ortsese’s social cameos seem to possess a Vermeer-like delicacy and intimacy, but seen not through a camera oscura or magic lantern, but instead through Caravaggio’s wild eyes or Brueghel’s lens of distortive, delirious clarity. The excellent translators’ introduction – and collaborative translation – highlight the shifting layers between vision and obscurity, blindness and insight; freedom and submission is another theme Ortese explores keenly and unflinchingly, here in the form of a power game between a younger and an older generation. There is, in post-war Italy, a distinct suspicion, often politically tainted, towards the reassuringly old, the historical, the aristocracy and the middle classes, their values, legacy and rights of say, towards old buildings, mores, or furniture and conventions of interior spaces, of inner and public lives; even books are to be admired only if sparklingly new – with a few, venerable exceptions, such as, quite tellingly, The Decameron by Boccaccio.

Whether writing fiction or factual narrative, Ortese gives us a very raw, neo-realist account of Naples, a daring endeavour of sincerity that cost her considerable criticism and even personal trauma as a writer. Her powers as a storyteller are substantial, and she deploys them without constraint, conjuring before our eyes worlds of almost unfathomable bathos, from which some readers may struggle to emerge: “amorphous poverty, silent as a spider, unravelling and then reweaving in its fashion those wretched fabrics, entangling the lowest levels of the populace which here reigned supreme. It was extraordinary to think how, instead of declining or stagnating, the population grew, and, increasing, became even more lifeless, causing drastic confusion for the local government’s convictions, while the hearts of the clergy were swollen with a strange pride and even stranger hope. Here Naples was not bathed by the sea.”

Fickle, facile reading of her pages could result in a sense that she is almost inhumanly harsh, senselessly exhaustive in her inventories of misery and cunning, usury and depravity, deformity, debasement. What Ortese seeks instead is to provoke in us a responsiveness to the tragedy close at hand, to the historical drama at our doorstep, that we more comfortably reserve for human lives that are too distant in space or time. In one of her pieces of social reportage, ‘The Involuntary City’, she exposes the reality of life for a community whose homes and space were devastated during the bombings at the end of the war. They now live in an old granary that had been converted into barracks, itself left derelict by the bombings, but available as shelter nonetheless. The images she paints for us are harrowing, the stories defy the stillness of all reason, yet, as she insists, we are required to look, and especially to study what she puts before us with the same focus and intensity as we would show towards an ancient society (shall we say Pompeii?). She urges us to hear the particular story – and not just scrutinise the demographics and statistics.

Ortese is a social anthropologist, a cultural historian, a documentarist, but also a kind of confessor, listening to every frequency of human wretchedness and pain, able to withstand, as an emotional filter and recipient, almost every shock of human tragedy. Hers is a disembodied voice, being lent to the service of so many voiceless existences. She is invisible in order to reveal – even if there seems to be no revelation, no vision, anywhere. One can almost see her walking, with her very particular dignity and presence, in the alleys of Naples and through the crowds of discarded humanity; she chronicles, with a luminosity that must have clashed beyond bearing with the surrounding squalor and darkness, giving us at least a sense of hoped-for illumination. She uses words the way others of her generation – Capa, Kalischer, Kertesz – used a camera to capture the moment humanity collapses but also shines in its trauma and fragility.

Ortese seems to have existed in an unremitting state of being shocked by life, while experiencing ‘the desire – rather the painful urgency – to render in my writing, the feeling of strangeness’, of alienation, of unsettledness.”

Ortese did not only see Naples through a neo-realist lens, she was also deeply committed to showcasing its history, its streets, cultures and traditions, its life of letters and of the mind. She gives us “that eternal Neapolitan crowd that moved on its own, like a snake struck by the sun but not yet dead”, as well as intimate glimpses of those who refused to leave, who strove to create, resurrect, enunciate. Her portraits of Luigi Compagnone, Domenico Rea and so many others, as well as the many portraits and smaller cameos of Naples, have a poignancy and immediacy achieved through an extraordinary assumed complicity with her readers. She can shift from elegiac prose (even when debating the prosaic) to clinical analysis with a fluidity that impresses with its magnitude and skill but also brands the reader with its urgency.

There is a very troubling, yet incisive, existentialist horror of humanity throughout, what she calls “the intolerability of reality”; Ortese seems to have existed in an unremitting state of being shocked by life, while experiencing “the desire – rather the painful urgency – to render in my writing, the feeling of strangeness”, of alienation, of unsettledness. Evening Descends Upon the Hills possesses a titanic sense of weight and waste, of a despair that cannot be lifted. Of the tragedy of witnessing as an outsider – almost of shameful moral complicity as to its causes and persistence. Ortese is particularly sensitive to, one could say she is haunted by malice, desperation, degradation, evil and baseness; also by a bureaucratic efficiency and institutionalised goodwill that is blind to humanity. It is said that Mary Shelley was inspired to write Frankenstein while walking along the Lungomare in 1818 – and perhaps by a similar sense of horror and awe as to the splendid wondrousness and desolation of mankind.

Ortese’s writing has something intensely obsessive, unavoidable – a compulsion to look closely at what repels and horrifies one most strongly, a sense of inescapable destiny and fatality. Human portraits melt into dire urban landscapes, and fade into social termini. She is a writer full of sharp angles, acidic aftertastes and ambiguities, a painter of words whose palette has developed a propensity for hues of morbid sepias contrasted by cerulean azures or emerald greens. She evinces ineluctable clarity and an almost ectoplasmic writerly presence, as if her texts were composed in and transmitted from some distant, immaculate and otherworldly dimension.

And yet every word and image cannot but strike a vital, deep, intimate chord; read her with audacity and trepidation; follow her as though on a pilgrimage; she will transport you to a world where language and narrative can reclaim their crucial urgency and value.

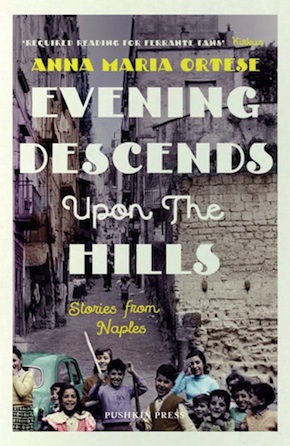

Anna Maria Ortese (1914–1998) is one of the most celebrated and original Italian writers of the 20th century. Evening Descends Upon the Hills brought her widespread acclaim when it was first published in 1953 and won the prestigious Premio Viareggio. Now translated into English by Ann Goldstein and Jenny McPhee, it is published in paperback by Pushkin Press.

Anna Maria Ortese (1914–1998) is one of the most celebrated and original Italian writers of the 20th century. Evening Descends Upon the Hills brought her widespread acclaim when it was first published in 1953 and won the prestigious Premio Viareggio. Now translated into English by Ann Goldstein and Jenny McPhee, it is published in paperback by Pushkin Press.

Read more

Ann Goldstein is an editor and translator, best known for her acclaimed translations of Primo Levi and Elena Ferrante.

Jenny McPhee is an author and translator. Her recent translations include Curzio Malaparte’s The Kremlin Ball and Natalia Ginzburg’s Family Lexicon.

jennymcphee.wordpress.com

@Jennymcphee

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.