A man should be able to do things

by Andrew FoxThe first time I tried to install the star nut, I had no soft blocks to cushion the dropouts and no vice to steady the fork, so I rigged up the front end and straddled the wheel, squeezing with my knees. I placed the nut in the mouth of the steering tube and covered it with a scrap of driftwood. I took a hammer from my father’s toolbox, weighed it in my hand.

The shed was crammed with old paint cans and broken patio chairs and musty cardboard boxes spilling lawnmower engine parts. When he was younger, my father had used it as a workshop. On summer weekends, he’d patched punctures and replaced chain guards for Mona’s friends and mine, and in winter he’d resealed hulls for small fishermen and varnished our mother’s furniture. I’d grown up fascinated and enraged by the hours he chose to spend secluded from us in there. But since I’d returned to him, and found his bike corroding, I’d taken it on as a project and made the shed my own.

Already I’d stripped away the rusted components and cleaned a decade’s worth of sand and grease from the frame. I’d raided the plastic boxes on the shelves for tools and inner tubes, and visited the bike shop in Balbriggan for a pair of chrome hubs, a brushed steel headset and stem, a set of aluminium brake levers and calipers and the most expensive chainset I could afford.

I swung the hammer and felt a nice shudder in my wrist, but when I lifted the wood the nut fell to the floor and rolled to rest by my heel. I set everything up and swung the hammer again but this time missed the centre of the wood and lodged the nut at an angle. When I tried to pry it out, it splintered in the hammer’s claw. When I fished for it, I cut a red slice in the meat of my thumb. When I leaned the bike against the wall, the wheels slipped their stays and the frame and fork keeled over. I stood for a while with my thumb in my mouth and looked at what I’d done.

In the kitchen, the kettle whistled beside a bowl of oats and raisins. A cup with a tea bag scrunched inside sat waiting on the worktop. I took a roll of plaster from the first-aid box beneath the sink and bandaged my thumb, lifted the kettle from its cradle and made the porridge and the tea. I set a tray and climbed the stairs to the study, where I found my father hunched over his desk, still wearing his blue bathrobe and black gorilla-foot slippers.

The desktop was a salvaged ship door from Napoleonic times; years before, Dad had planed and sanded it and bolted it to driftwood legs. The shelves above his head held complete boxed sets of Popular Mechanics, Civil Aircraft Markings, Propliner Magazine and Automotive Repair, as well as his slide collection, his stamp collection and his library of films recorded from TV. I set the breakfast things down in front of him. He stared blankly at the cup and bowl, then stretched his right hand in the wedge of light that angled in from the high window. The fingers were surprisingly slender.

“You see that?” he said.

“See what?”

“That ring.”

“That’s your wedding ring, Dad.”

His eyes were quick. “Christ, I know that. You dirty-looking eejit. I’m not all gone yet that I’d forget a thing like that.”

His finger tapped the freckled hollow at his temple. He held out his other hand, the third finger of which showed a pale band of soft skin beneath the knuckle.

“But I usually wear it on this finger is the thing. I change it sometimes when I have to remind myself to do something, you know. Your mother taught me that, but… What was it, is what I want to know. Do you understand me? I’ve forgotten what it was I was supposed to remember.”

“It’ll come back to you,” I said, as evenly as I could.

Before my second attempt at installing the star nut, I tuned the spokes, ran new tubes inside new tyres and bolted the wheels to the frame and fork. I greased the headset bearings and screwed on the compression rings. I magic-markered a red X in the centre of the scrap of wood and positioned it over the mouth of the steering tube. Then I raised the hammer, brought it down and felt a shudder and a little give. I repositioned the wood and brought the hammer down a second time. A third.

The wood slipped, and I knew before I looked that the nut had broken. When I did look, I saw a long fissure that my hammer alone could not have caused. It was the result of an original flaw, a weakness in the casting. I took a thin piece of sawn-off scrap metal and hammered the nut all the way through the hollow tube to the floor. I knew that I would have to take the bus to Balbriggan to get another one. But as I gathered up the pieces and flung them in the bin, I took solace from the knowledge that it was the nut, and not my method, that had been defective.

On my way to the bus, I offered to walk Dad to his doctor’s appointment. We took the cycle path that hugged the dunes behind the house. The sky was low above a tidal plain dark with seaweed, the waves a deep icy blue where they broke on the near side of the island line. The arcade and the chip shop were shuttered for the season. Dad greeted the drunks huddled on the wall by the public toilets each by name. We cut through the lane by the caravan park and came out on the main street at the monument to Great War dead. At the surgery, I said goodbye but found myself unwilling to leave.

“Do you want me to come in with you?” I said.

“But you’ll miss your bus then, won’t you?”

“Yeah, but… You can get home all right?”

Dad looked past me up the street. In the near distance the red front door of the house was visible. He laughed.

“Fuck off, you,” he said.

Back at home, I walked from room to room looking for Dad. His bowl of porridge and his cup of tea were still upstairs, untouched… maybe he had gone to the bookies for a flutter or ducked into the Lifeboat for a pint.”

The owner of the bike shop in Balbriggan had a high forehead and a cabled throat, oily fingernails and plastic glasses mended with electrical tape. Behind him was a corkboard to which faded posters from suppliers were pinned, in front of him a glass case strewn with so many parts it looked as though a bike had exploded in there.

He wanted to talk about the merits of the new Shimano range and about his sons’ successes in the downhill racing leagues. I rushed the transaction as politely as possible, half-ran for the return bus and stood up front by the driver watching the rocks of the coastline blurring past the window.

Back at home, I walked from room to room looking for Dad. His bowl of porridge and his cup of tea were still upstairs, untouched. As I cleaned them at the sink, I told myself that he must be stuck in the usual queue behind wheezing smokers and diabetic fatsos. Or maybe he had gone to the bookies for a flutter or ducked into the Lifeboat for a pint.

I went to the front door, opened it. As I searched the empty street in both directions, my phone rang: Mona.

“How’s Dad?”

“He’s fine,” I said.

“Can I speak to him?”

Her voice was sleepy, the background loud with RTÉ radio and the sound of Colm and the kids laughing together.

“Not right now,” I said. “I’m not sure where he is.”

I could imagine my sister’s eyes shimmering the way they did whenever anger started to boil. Her top lip, I knew, was clamped between her teeth and her ears moved as she worked her jaw, the skin stretched tight at the corners of her eyes.

The third time I tried to install the star nut, I took the nut from the bag and laid it in the mouth of the steering tube, covered it with the scrap of wood and brought the hammer down. The nut went in first time. I slid a half-inch spacer over the end of the tube and bolted the stem in place, turned the Allen bolt in the top cap until I felt it catch and swivelled the stem from side to side. I lifted the front end, bounced the tyre off the ground and tried to rock the headset but it wouldn’t budge.

I bolted the handlebars to the stem, slipped on the brake levers and gear shifters and secured them all in place, greased the ends of the handlebars and slid on a new set of rubber grips, greased the bearings and threaded the axle and screwed in the bracket cups, screwed the pedals to the crankset and bolted that to the axle, hung the derailleurs, attached the new chain, hung the brake calipers and set the pads and ran all the cables through their sheaths, bolted the saddle to the seat post and coaxed that into the frame, screwed on mudguards and reflectors and a headlamp and a rear blinker.

I wheeled the bike out of the shed and climbed into the saddle. I pushed off, rolled to the back gate and slid back the bolt. A dog trotting on the cycle path inclined its head and watched me. The wind whistled through the dune grass. I didn’t move.

Through the living-room window, I watched the sky threaten rain. I turned on the TV and flipped between people making over their houses or faces. I made a cup of tea and let it go cold, peeled back the bandage to see how my thumb was healing. I ached for a cigarette. I missed my mother.

I heard the front door click, heard the scratch of Dad’s shoes on the doormat. I was up from the couch and standing next to him before he knew it.

“You gave me a fright,” he said, unwinding his scarf from his neck. “You’ll never guess who I ran into. Remember Noely Caldwell? The old fishmonger? He’s not been well, God bless him. Something with his heart.”

“Where the hell have you been?”

Dad frowned innocently and offered a red plastic shopping bag.

“I was talking to Noely. In his shop. I got us dinner.”

I left him in the hall and went to the kitchen to call Mona back. She was on her way out to me, she said, her voice levelled to a flat calm.

“It’s okay,” I told her. “He’s just got in the door.”

Mona’s voice shuddered and she and Colm began exchanging muffled words. I waited.

“Look,” she said, “we’re coming down tomorrow. We need to talk to both of you. It’s just… I need to talk to both of you.”

Dad took a paper parcel from the bag and unwrapped it by the sink to reveal a silver fish. He took a wooden cutting board from the cabinet and a shining cleaver from the block.

“Don’t!” I said, a little too loudly.

“What?” Mona said. “What’s happening?”

I cupped my hand over the mouthpiece.

“I’ll do that in a minute,” I told Dad, who dropped the cleaver and threw up his hands and stalked out into the garden. I stared at the door for a moment.

“What?” Mona said. “What is it?”

“He was trying…” I said. “I overreacted. He was about to butcher a fish.”

I could hear Mona’s kids again in the background and Colm closing cupboards. I kneaded my forehead against the pain behind my eyes and discovered that my hand was trembling.

“Look,” Mona said, “you’ve been very good to him. I just think that maybe now’s the time to move him. I’m sorry. I’m just so worried and so frazzled and I can’t –“

“Easy, Mo,” I said. “We’re all right. We’ll figure it out.”

“I’m glad it’s you out there and not me. Does that make me a terrible person?”

Through the kitchen window, I could see the light go on in the shed and Dad’s silhouette moving about in there.

I washed, peeled, sliced potatoes and dropped them into a pot of water to boil. I scraped the fish’s scales, broke sprigs of dill and thyme from the herb box and chopped them, picked a lemon from the fruit bowl and cut it into discs, took salt and pepper from the spice rack and stuffed the wet pink cavity until the fish bulged at the gills. I laid it on a roasting tray and slid it into the oven.

Outside it was dark already. From beyond the back wall, I could hear the sea rolling, and through the shed window, I could see Dad standing beside the bike, one hand resting on its handlebars. As I walked the garden path, I felt moisture from bent-over grass fronds soak the ends of my jeans. I resolved to mow the lawn in the morning, unless the rain came back. I shouldered the sticking door and stepped into the shed.

“This is my bike,” Dad said.

He had taken off his jacket and flung it in a dusty corner. His shirtsleeves were rolled up, his top button undone to show the fraying neckline of a white vest.

“How was the doctor?” I said.

“But you rebuilt it.”

Dad tried to rock the headset.

“Yes,” I said. “I did.”

“Good. That’s good. You might have a talent for this, you know? And that’ll stand to you. A man should be able to do things.”

Dad flipped the bike over and rested it on its saddle and handlebars.

“I’ve been working on something inside myself I’ll show you later on,” he said. “But it’s a surprise for your mother, now, so don’t go telling your sister. She can’t keep a secret, that girl.”

He turned a pedal, pressed the shifter and grinned as the chain moved smoothly up and down the gears.

“Good. That’s good,” he said. “But she looks up to you, you know. When she starts in school you should take care of her.”

Dad’s shoulder blades flared through his shirt as he turned the bike over and laid it on its tyres.

“Look,” he said, a bead of sweat forming in the crease of his lip. “I know you don’t know what I’m on about now. But you’ll understand me when you’re older.”

Dad’s hand moved along the crossbar to the saddle. I took a step towards him, then a step back.

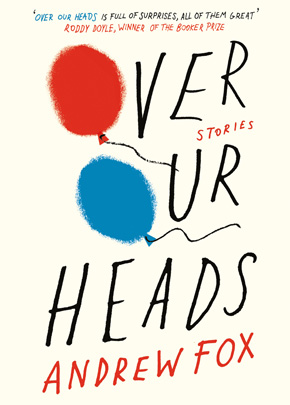

From the collection Over Our Heads.

Andrew Fox was born in Dublin in 1985 and lives in New York. His stories have featured in journals including the Dublin Review and the Stinging Fly. Over Our Heads is published by Penguin in paperback and eBook. Read more.

Andrew Fox was born in Dublin in 1985 and lives in New York. His stories have featured in journals including the Dublin Review and the Stinging Fly. Over Our Heads is published by Penguin in paperback and eBook. Read more.

Read Andrew’s discusion of Claire Keegan’s ‘Men and Women’ in Favourite Stories.