Alone at last: The secret of Marian Engel’s Bear

by Dorian StuberA woman is sent to an island for a summer. The island holds little more than a house, although admittedly a big one for this remote territory, and strangely shaped too, with eight sides and no real corners, two levels, many windows – ridiculous anywhere but especially here, where you need a fire most of the year. The house boasts a library and the woman, who is a librarian, an archivist really, a historian of this territory, a place often taken to have no history at all, is meant to catalogue it. “Did anyone tell you,” asks the man who brings her to the island in a snarling motorboat just before he roars back up the river to the closest thing that passes for a town, “about the bear?”

Anyone had not.

There has always, it seems, been a bear on the island, insisted upon by all its owners, from the Colonel who first settled here through a line of subsequent Colonels, the last of which, in reluctant obedience to the family will stating the estate should pass to whichever son became a Colonel – a decree made by a man apparently unable to conceive of a generation without male issue – was a woman named Colonel. The librarian asks, Why a bear? Heraldic emblem? Totem? Symbol of the family’s domination over the land? The man doesn’t know.

He does know, though, that the bear is not a pet. It wants minding. She’ll want to mind herself around it, too. She must heed expectations, as powerful here as in the city she has left behind, more powerful, actually, because the artificiality of those rules is so clear here, in the middle of nowhere. Expectations about how women – and bears – should behave.

The bear, chained in a byre, is smaller than she expected, shrunk into itself, fur matted, eyes dull. Although she is not fond of animals, she can’t let the bear live like this, and the animal’s hold over her (part fear, part desire) only grows when something she is fond of, or at least knows her way about, whets her interest. Taking stock of the library, flipping through books that haven’t been off the shelf in years, she is surprised by slips of paper that flutter from between the pages. Each offers a fact about bears: their classification, their anatomy, their habits, their role in myths. A veritable ursine I Ching. Kamchatkans, she learns, use the sharpened shoulder blade of the bear as a scythe. The bear’s gait is plantigrade, its teeth tuberculated, its stature large. Males have a bone in the penis. So many surprising facts.

Before long bear has the run of the house. He sprawls by the fire of an evening, more majestic than any rug, while she reads and runs her feet through his pelt. Somewhere along the way the bear has become bear; ‘it’ has become ‘he’.”

The librarian thinks about bear more and more. As if conjured from her thoughts, an old woman, a former caretaker of the house, suddenly appears – an indigenous woman wizened and bent, a real fairy-tale figure except for the motorboat she arrives on with her grandchild at the tiller. The woman tells her, with a look she can’t decipher, that the bear is a good bear. Shit with the bear, she cackles, and he like you.

She does. It works.

Soon she’s undoing the chain, taking bear into the burning cold of the northern river, rolling with him in the shallows, watching him paddle like a toddler, burning with pride when he comes out glistening and clean. She shares her meals with him. Before long bear has the run of the house. He sprawls by the fire of an evening, more majestic than any rug, while she reads and runs her feet through his pelt. Somewhere along the way the bear has become bear; ‘it’ has become ‘he’. Bear, after all, is indubitably male.

Oh bear, she thinks, what am I going to do with you?

Late at night, a little drunk, staticky music crackling on the radio, she admits she has been lonely. It’s depressing, how she’s let herself be fucked by her boss once a week, both pretending to be shocked and shocking as they rut on her desk when she knows he really only cares for eighteenth-century keyholes while she cares for, well, she’s not sure what, just not this.

She makes bear dance with her, he shuffles on hind legs unsteadily. And then she masturbates, which interests him, he begins to lick her, all over. She guides him: “with little nickerings she moved him south.” He is more assiduous than any man has ever been. It’s a real folie à deux, the two of them hiding away together on the enchanted isle. Or maybe just a folie. Bear will not, cannot, reciprocate, often loses interest, turns away and farts. Matters come to a head, events reach a climax – there’s no way to say it without double entendre, why is the language of storytelling so sexualised this way? Her attempt to become even more intimate is a disaster. Bear rakes her back with his claws; the woman has a narrow escape. She is chastened. She packs up, takes the boat back to her car, and begins the long drive south to the city. But she won’t go back to her old life. She has done no wrong. On the contrary she knows now how many wrongs have been done to her. Day turns to brilliant night, all the stars shining. Ursa Major guides her home.

—

Do you have a secret book? One that is yours alone? Maybe not the book you love most in the world, maybe not the best book you’ve ever read, but a book you came to all on your own, maybe through circumstances you can’t even remember. A book you love even more when you realise nobody else seems to know it. Bear – a novel by the Canadian writer Marian Engel, first published in 1976, the events of which I’ve retold here – is my secret book. But with the arrival of a new UK edition (Daunt Books) joining existing Canadian (McClelland & Stewart) and US (David R. Godine) editions, it’s not going to be secret for much longer, and I don’t know how I feel about that.

The main character, the librarian, is Lou, her gender-neutral name just one way the novel imagines how women might escape the limitations of a world dominated by men. The city is Toronto, the island somewhere in northern Ontario, probably in the Algoma district of the Canadian Shield, north of Lake Huron. The house is a Fowler’s Octagon, the brainchild of the phrenologist Orson S. Fowler, who published A Home for All, or A New, Cheap, Convenient and Superior Mode of Building in 1850, in which he offered a design modelled on the structure of the brain. The novel, in fact, is fascinated by heads and the questions of legibility they incite. What’s going on in that head of yours, bear? Lou wonders. A good question to ask at an estate named Pennarth, Welsh for ‘bear’s head’. Especially by a woman tasked with cataloguing a library that, as the writer Aritha van Herk puts it in an excellent essay on the novel, “is typical of a [British, male] nineteenth-century mind.” (The collection includes Edward John Trelawny’s recollections of Byron and Shelley; Lou gleefully imagines the fascination and disgust her affair would incite in these ostensibly rebellious poets.) Bear demands that we take seriously the possibility that beings not typically believed to have much of anything going on in their heads – women and non-human animals especially – are just as, no, more worthy of interest than those men who have created and enforced the conventions of politics, history and science by which we live. Yet the novel refuses to equate women and animals, rejecting that age-old comparison, which is nothing more than a backhanded compliment that only ever denigrates women. It’s clear to Lou that there is plenty going on in bear’s head. But she never figures out what.

Lou fails because she has projected her own desires, longings and thoughts onto bear, replicating the violence of the patriarchal and colonial system that excludes people like her. But Lou needs to make this mistake. Paradoxically, she needs bear to help her become self-sufficient. But she also needs – and this is the reason she is the book’s hero, not just its protagonist – to have the grace to accept this domination for what it is. In so doing – in accepting that she can’t force herself on bear, either sexually or emotionally – Lou displays a kind of tact or modesty I would be tempted to call Canadian and affirm proudly if Canadians weren’t always so proud of being the silent, sensible and selfless cousin to our British and American relatives.

—

The very idea of a secret book risks being similarly smug, at least if it’s motivated by pride at having found an unknown prize. Happily, however, such self-satisfaction is easily disabused by a novel as committed to challenging convention as Bear. Engel disparages at least three cherished beliefs: colonialism (the original Colonel, an Englishman who won a commission in the Napoleonic Wars, distinguishes himself only by the looseness of his bowels: family legend has it that while sitting “on a portable military thunderbox groaning with summer dysentery” he picked Cary’s Island out with a pin from an atlas of the New World); male sexual prowess (her boss, her past lovers, the local guide with whom she has a brief and unsatisfactory dalliance: all are risible, less appealing than the morels, “strange decayed phalluses” she discovers in the woods, delicious fried in butter); and even the certainty of a male literary and artistic tradition (the guide is named Homer; he’s no bard, but he’s definitely blind, possessed of the stupidity of those who never need to question their place in the world since they made it for themselves).

We might indeed at times raise our eyebrows. But what if, instead of secretly thrilling to our moralising responses of shock, dismay or even disgust, we stopped to think about who we feel emboldened to judge and for what?”

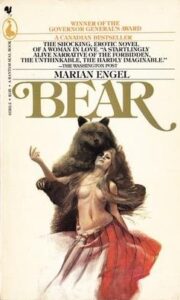

Maybe the whole idea of a secret book is silly too. After all, one reader’s secret treasure is another’s prize-winner. If anything, Bear is an open secret. It won a prestigious literary prize, the Governor General’s Award, given out that year by a committee including Alice Munro, Margaret Laurence, and Mordecai Richler. Hard to imagine more canonical Canadian literary figures at the time. Not everyone was smitten, of course. Her editor at Harcourt, Engel’s American publisher, passed on the book, noting “its relative brevity coupled with its extreme strangeness” (as if these were bad things!). One critic famously called it “spiritual gangrene”. But it was well reviewed in The Globe and Mail (then, at least, the Canadian paper of record) and The Times Literary Supplement. A quick online search leads to one essay after another encouraging readers to discover this underappreciated work, famous for not being famous enough. Or for being infamous. Because even readers who don’t know anything else about Bear know that it is lurid or tawdry or something.

Yes, the book frankly depicts Lou’s sexual desire – and her pleasure. (I think its insistence on that pleasure, not the form the pleasure takes, is what really bothers people; as Engel puts it: “what [Lou] disliked in men was not their eroticism, but their assumption that women had none.” It is not only men who believe this.) Bear is not, however, prurient or pornographic. It doesn’t even feature much ‘bear sex’ at all. The unhealthy experiences it features aren’t libidinal but oppressive. One way to read the novel is as a case study demonstrating how easily a person routinely defined as insufficient turns to obsession to compensate for her inability to find self-fulfilment. Something inside her, Lou thinks, is “too much”. A thing that drives her to first vandalise the house of a rival and then carve anagrams of the woman’s name onto her arm, all in in the search for some man’s attention – maybe the same man who, as she says of one lover, liked her only as long as “olive oil didn’t crease her belly”. The same thing – some quality of excess – leads her to get on all fours and slurp cornflakes out of a bowl alongside bear, or, in one of the novel’s most infamous lines, “cradle[ ] his big, furry, asymmetrical balls in her hands.” But what if this thing wasn’t, as Lou has been made to believe, a fault? What if there’s nothing wrong with her? And how come men aren’t ever “too much”? Why isn’t the guy who left her for the other woman a problem? Why doesn’t her boss feel as ashamed of himself as she does? Reading Bear, we might indeed at times raise our eyebrows. But what if, instead of secretly thrilling to our moralising responses of shock, dismay or even disgust, we stopped to think about who we feel emboldened to judge and for what?

I’m worried I’ve made Bear sound like a dutiful paean to second-wave feminism. When in fact it is exciting, joyful and alive. Bear is a sweet, glorious, funny novel (those bear balls!), infected with the delirium of northern summer. It’s a love story, too. The love of Lou for bear, of course, but also of Lou for the island, and, most movingly, of Lou for Lou. Bear is a novel of joyous solitude, being alone instead of being lonely. Love is present already in its epigraph, which Engel takes from the art historian Kenneth Clark:

Facts become art through love, which unifies them and lifts them to a higher plane of reality; and in landscape, this all-embracing love is expressed by light.

I’ve long struggled to understand the stuffy certainty and intricate syntax of this sentence, which is nothing like the novel it introduces. Having read and taught the book many times I now think Engel wants us to both wrestle with Clark’s claim and dismiss it as a joke. Our wrestling has to contend with the ambivalence of the word ‘landscape’. If it means a feature of countryside or land – “A beautiful landscape stretched out before us” – then Clark might be saying: nature (‘facts’) is different from art; nature becomes art through the mediation of light; light is a metaphor for a way of seeing, an approach, a viewpoint. But if ‘landscape’ means a type of visual art – “Cezanne painted dozens of landscapes of rural Provence” – then Clark might be saying: nature (‘facts’) gets transformed into art by love; landscape art makes that transformation by the way it depicts light. What links the two seemingly antithetical meanings of landscape is the imposition of human vision onto the non-human natural world. There are no landscapes without someone there to see them.

This imposition has its uses – it leads to art, for example – but it’s not far from, maybe even indistinguishable from abuses such as the exploitation of the non-human world by humans. Here’s where the joke comes in. Everything in Bear challenges the idea of unassailable conviction. Even Clark’s seemingly benign assertion is composed of the same certainty that has led, in Engel’s view, to domination of all kinds: men subordinating women; white settlers devastating and ruling the land they called North America; humans killing and abusing non-human animals (“intellectual fingers,” Engel writes, “destroy”). In imagining a love story between a woman and a bear, Engel imagines a different reading of Clark’s statement, one that affirms a more tangible, practical relationship between love and light.

Bear is filled with descriptions of the light of a northern summer. Here’s Lou on her first day at Pennarth:

The morning light was dappled, fallow, green, a moving presence at the windows. The kitchen swam in an underwater gloom.

Lou soon leaves the kitchen – a place she visits only to open a can of beans and make coffee – for the light-filled library, another, more exultant watery space: “She waded around the room slowly, reverently. It was a sea of gold and green light… an astonishing tunnel of green.” The next morning, after a sudden late spring storm that leaves behind soft, thick snow that drips from the trees as soon as the sun hits, “the light in the bedroom was extraordinarily white.” Lou, whose office at the Historical Institute is the basement, who is likened to a mole, who, in a brilliant description of the grinding Canadian winter months, “scurr[ies] hastily through the tube of winter from refuge to refuge”, is now thrust into the light. The island might not be big, but it is for her a magical expanse. It is a changeable place – islands, she reflects, are “water-creatures” – boggy, “spongy, creeping and seething with half-born insects”, thick with brush broken only by a pond surrounded by maple trees, in one of which a crow’s nest had been built, with a ladder she climbs to survey her domain.

Over and over she calls it her kingdom. The language of royal space combined with the novel’s air of magic makes me think of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Lou, having internalised the attitudes of the world (as a woman she has her place in the world, and challenging that order threatens to reveal her as a monster), fears she is Caliban. In her moments of study and work, she is perhaps ethereal Ariel. In her worst moments – her fears about herself and her actions – Lou is Prospero: if not self-satisfied then similarly obsessed with knowing and ordering, and as violent as the former Duke of Milan in her use and abuse of others, especially bear, who never asked to be the object of her sexual desire.

Or maybe she is Miranda. Not naïve, although men have tried to keep Lou in her place too, but wondering and delighted. And what Lou takes most joy in, ultimately, is neither the island itself nor bear, but herself. As van Herk puts it in her afterword to the Canadian edition, the novel breaks the male/female dichotomy by introducing the non-human animal: “A woman and a bear: a bear and a woman. Alone at last.” The point is that this relationship does not involve domination. The oppressed doesn’t turn oppressor. In her most heartfelt moment, Lou makes a plea: “Bear, make me comfortable in the world at last… I want nothing but this from you.” Summer ends, the magic spell is broken, but what Lou loses is not just her deranged idea that she could love a bear, but the deranged ideas that society has demanded she live by. Not so that the oppressed can turn oppressor. But so that she can, as much as possible, be free. She leaves behind the file of bear facts, she quits her job, she breaks off with her boss. She has her epiphany, however brief: “For one strange, sharp moment she could feel in her pores and the taste of her own mouth that she knew that the world was for.” Not for her. But not for her to be used by it, either.

Assigning the book always makes me a little nervous. How will the students respond? Some find it disgusting – that’s rare, though, and interestingly happens much less often now than it did twenty years ago. Some are disappointed – they don’t come out and say so but it’s clear they wished it were filthier, more shocking. (What’s wild and unruly in this novel are its dreams, not any perversities.) And some are frustrated – disappointed that Lou violates Bear, uses him as a plaything, is an abuser. I do my best to show them how the novel critiques each of these responses. Van Herk’s phrase “alone at last” is apt: not the expression of the rake before his, or in this case her, conquest, but the sigh of relief of a woman who has been given the gift of being able to see herself as a person.

—

If van Herk is right about the essential dyad at the heart of the book (“A woman and a bear: a bear and a woman”), a dyad that births a single, singular self (it is important that bear never becomes a prince), then Bear would not seem to have been written for me, a white cis man of white settler ancestry. But there is a lot for me to learn about a world without people like me. Besides, the idea of being alone appeals across gender lines. I think it’s the novel’s evocation of relieved, even exhilarated solitude – alone at last – that makes Bear special for me. Having grown up in Canada, I know what it’s like to feel overwhelmed by the land. But also to be thrilled by the disparity between its vastness and my own frailty. To cherish the long days and short span of northern summers, in which shadows stretch out in evenings that seem to go on forever, in which plagues of insects are with luck dispersed by ever-present breezes, and in which it’s always smart to bring a sweater – the cold could come anytime now. I needn’t have had these experiences to enjoy Bear, but they are part of what makes the book mine.

I know I love Bear unreasonably. But surely you can be unreasonable about a book about being unreasonable. And what is love but unreasonableness incarnate?”

Certain books, says the essayist Vivian Gornick, are private pleasures. Ungainly, imperfect books that you love even though you fear your love is disproportionate to the reality. Books you love the way parents love their children. That’s the love I have for Bear. Not that it is ungainly, especially, though its main character berates herself for her gaucheness. Yet it is neither perfect nor pretty, never elegiac and seldom wistful. On the contrary, it is often stark, as tough and unforgiving as the Canadian Shield, lyrical only about the island itself. I know I love Bear unreasonably. But surely you can be unreasonable about a book about being unreasonable. And what is love but unreasonableness incarnate?

Here’s a bit I’m especially unreasonable about. Lou’s time on the island is almost over. The birches are yellowing. Fall is on the way. Something has broken between her and bear: “the high, whistling communion that had bound them during the summer.” The high, whistling communion. I love that phrase, the way it speaks in language at once literal and metaphorical to describe connections that matter all the more because they come to an end. Like a short summer. Or like the idea of a secret book.

Just as parents can’t help but will the world to feel about their children as they do themselves, I can’t help but share my private pleasure. I can’t keep my secret to myself; the only way I know it’s a worthwhile secret is to tell it to the world. I’ve shoe-horned Bear into every course I could, nattered on about it on social media, put it on every list I’ve ever made of favourite or desert-island books. How could I do otherwise? To even say “I’ve got a secret” is to begin to undo it, to dissolve the secret even before its exact nature is revealed. The secret can no longer be a secret for its full power to be felt. This is at once disappointing and heartening. We lose something that belonged just to us, but we gain an audience. It seems important that we say we share a secret. As Bear prepares to be discovered by yet another set of readers – who knows, maybe this time for good, maybe before long it will be ridiculous to even think of it as a secret favourite – I recognise that any disappointment I feel at the prospect, the loss of my Bear, was built into my love from the beginning. Besides, losing the secret means gaining a confidante. You, me, Bear: alone at last.

Dorian Stuber is Isabelle Peregrin Odyssey Professor of English at Hendrix College, Arkansas, where he teaches critical theory, Holocaust studies, creative non-fiction and Anglo-American literature. He received a PhD in Comparative Literature from Cornell University, and his articles and reviews have appeared in journals including Numéro Cinq, Open Letters Monthly, Forma and Words Without Borders. He is the editor of Critical Insights: Holocaust Literature (Salem Press, 2016) and frequently blogs about the literary arts at Eiger, Mönch & Jungfrau. He is working on a book project about the Holocaust, pedagogy and world literature.

Dorian Stuber is Isabelle Peregrin Odyssey Professor of English at Hendrix College, Arkansas, where he teaches critical theory, Holocaust studies, creative non-fiction and Anglo-American literature. He received a PhD in Comparative Literature from Cornell University, and his articles and reviews have appeared in journals including Numéro Cinq, Open Letters Monthly, Forma and Words Without Borders. He is the editor of Critical Insights: Holocaust Literature (Salem Press, 2016) and frequently blogs about the literary arts at Eiger, Mönch & Jungfrau. He is working on a book project about the Holocaust, pedagogy and world literature.

eigermonchjungfrau.blog

@ds228

Author portrait © Becca Bona

Marian Engel (1922–85) was born in Toronto and grew up in the Ontario towns of Brantford, Galt, Hamilton and Sarnia. After living abroad and teaching in the United States and Europe, she returned to Canada in 1964 and settled in Toronto. Her other novels include No Clouds of Glory, Inside the Easter Egg and The Tattooed Woman. She was a founding member of the Writers’ Union of Canada and served as its first chairman in 1973–74. Bear is published in paperback and eBook by Daunt Books.

Marian Engel (1922–85) was born in Toronto and grew up in the Ontario towns of Brantford, Galt, Hamilton and Sarnia. After living abroad and teaching in the United States and Europe, she returned to Canada in 1964 and settled in Toronto. Her other novels include No Clouds of Glory, Inside the Easter Egg and The Tattooed Woman. She was a founding member of the Writers’ Union of Canada and served as its first chairman in 1973–74. Bear is published in paperback and eBook by Daunt Books.

Read more

dauntbooks

@DauntBooksPub