Mariano takes stock

by Ronaldo WrobelThere was no doubt when the Castro & Castro Industries shares skyrocketed on the Stock Market: the family had sold control of the company to the Bank of Massachusetts. The long transaction, involving much back and forth, dashed the hopes of many investors. Rumour had it that Castro Sr. broke down in tears and actually spat on the gringos. His eldest – and most sensible – son had been the one to negotiate the deal, to the shareholders’ relief. Now those papers were worth gold. The Bank of Massachusetts intended to make a big splash in the industry, entering the sector with force and exporting to the Mercosul nations.

It was 4 o’clock, Thursday afternoon. Mariano was at the wheel in Barra da Tijuca. The Mercedes’ speedometer had reached the price of Castro & Castro stock: 140. He was disgusted, absolutely disgusted, having sold the shares the day before for a measly 60 reais, missing out on an appreciation of more than 130 percent. Shit, shit, shit! He wanted to take it out on his office, slam the tabletops, let the secretary have it, even give it to the gay little server boy who interrupted meetings coyly whispering: sugar? sweetener? The humiliation was unbearable! He of all people, a financial market expert: fixed income, equities, derivatives, swap out, leasing, export notes, hot money. Because that day his Wall Street savvy was on break. As he sped along the streets, Mariano keyed into his cell phone and ordered one of the broker’s employees to track Castro & Castro stock. For two hours, the quotes and the speedometer were in synch: 130, 135, 140. The speedometer could go up to 240. And the stock?

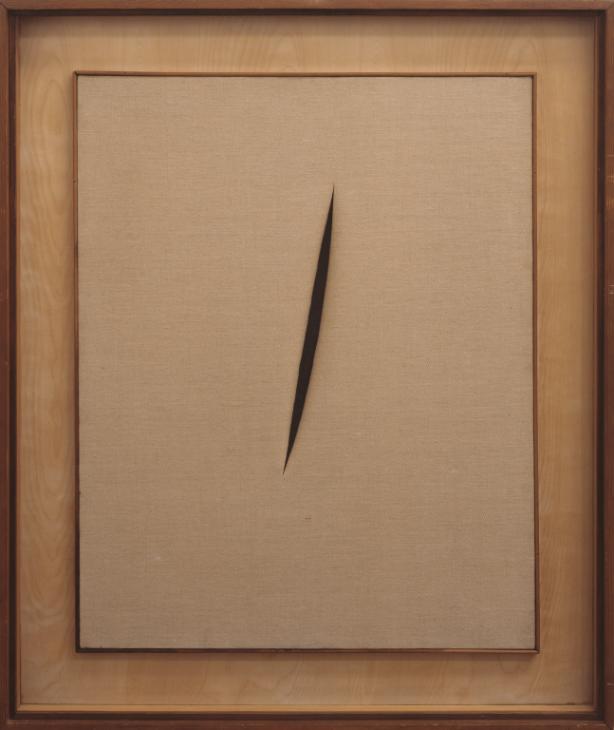

It didn’t get above 145. With trading closed, Mariano downshifted and went home. For the first time ever, he surrendered to the garage attendant the car he didn’t hand over to anyone. He entered his home downcast, without glancing at the paintings, sculptures and china adorning the entryway. No one knew, but that collection was the preferred target of Mariano’s rage, used to being shattered from time to time. The maid would be horrified by the shards strewn all over the floor, slashed canvases, damaged walls. But the next day her boss would replenish the supply of objects he himself called his “next victims”. His psychiatrist always recommended that Mariano destroy just one piece per crisis: “Concentrated hatred is better than diffused hatred.” That afternoon, Mariano decided to test the theory.

Mariano angrily considered a blotter from Dom Pedro II’s court; an impressionist painting depicting a bird – ready to take flight out the window… Bad luck befell a crude clay vase purchased in a remote corner of Brazil.”

He sauntered down the hall with the cold-heartedness of an executioner. The canvases, china and crystal shook beneath his gaze. Mariano angrily considered a blotter from Dom Pedro II’s court; an impressionist painting depicting a bird – ready to take flight out the window; an early-dynasty Chinese soup tureen, acquired at a London auction house. Each artwork had its history, and each history a potentially dramatic fate. Bad luck befell a crude clay vase purchased in a remote corner of Brazil.

2002, election eve. At the palace, the governor had been direct: “We have a mission to accomplish. I’m going to order the state bank to issue bonds to finance my candidate’s campaign.”

“Brasilia authorised that?” Mariano asked.

“Fuck Brasilia! I issue here, I sell here, I pay here!” he summed up. “Everything’s taken care of. A colleague has already bought the bonds. He’s going to get rich: thirty-five percent monthly interest!”

The following week, Mariano had an office in the palace itself, a fleet of cars, and a staff that even included prostitutes at his beck and call. He made up the state bank’s accounting, camouflaged losses, and issued said bonds, hand-delivered to the governor’s pal.

Mariano personally traversed the backcountry, three hours in the official car on an asphalt strip. He discerned the misery along the way in double: he had drunk a bottle of the cachaça that was cultural – and liquid – patrimony in those parts. He leapt out to take a leak in some village called Poconé. He relieved himself in a swampy area, between a cluster of shacks divided by lanes of dirt and gravel. On a corner sat a tray of clay vases, some poorly crafted, some smooth. A very humble and wrinkled woman said: “Five each.”

Mariano pulled out his wallet. “I’ll take one.”

And the woman smiled without smiling: “With flowers? Without?”

“Whichever. I only have a ten, keep the change.”

She refused. He should take another vase if he wanted.

“All right then,” he said. “Good deal!”

“Good what?”

“Deal!” Rubbing his fingers together: “Moola, dough!”

“Over there.” The woman pointed to two loaves of bread.

Mariano sighed, expressing his impatience.

“One day I’m going to sell your vases and make a profit, get it?”

“You’re going to sell my vases?”

“Only when you die. Dead artists are worth more than living artists, understand? Here, take my card. Hang on to it. Let me know when you die.” And he turned his back, without hearing her.

“My name is Jozelina!”

Mariano stumbled getting into the car and dropped one of the vases.

***

After smashing the other vase, Mariano called the maid and locked himself in his room. Tranquilisers and sleeping pills afforded him twelve hours under the covers lulled by the arctic air-conditioning.

The next morning, he woke up with an obsession: recouping the exact value of what he had lost (or failed to gain) with the Castro & Castro appreciation. The algorithms on his calculator were all odd numbers. There’s the ticket to happiness.

Four days later he had made up the difference and then some. He celebrated at a seaside resort, in the arms of a blonde with whom he returned by helicopter to Rio de Janeiro. They hopped out, windblown, at a club heliport. Windblown and famished. At a Japanese restaurant, they ordered sushi served on a boat that drew attention from other tables. The blonde greeted a celebrity as drunk on sake as she was. Mariano almost ran down a cyclist as they zigzagged through Barra. He blamed the Mercedes’ sensor but the blonde wasn’t interested. She wanted to get home to sleep.

On the hallway table sat Friday’s mail: bills, bills, ads, flyers, invoices, all printed, all on letterhead. And one blue envelope with no emblem, initials or seal. Coarse paper, two stamps, unknown sender. Mariano opened it out of curiosity.

Dear Sir,

I’m carrying out the request of Jozelina da Silva Cruz, my neighbour, who died yesterday. Before taking her leave, she asked me to tell you that you can sell her vases now. May God keep her and bless us all.

Laura

Poconé, 29 October 2010

Mariano stopped. He remained standing in the hall. He reread the letter twice and headed to the kitchen. He took a shower, wrapped himself in a terrycloth robe, and sat on the terrace. It was a crystal-clear, star-filled night. Fishing boats circled in the Atlantic until dawn tinted the horizon rose. The blonde slept soundly. Mariano packed a small suitcase and went to the airport. He caught the first plane.

In Poconé: “Do you have another vase made by her?”

Laura was taken aback. She brought a crude piece from inside.

“How much do you want for it?”

Since Laura didn’t answer, Mariano gave her a wad of bills. Then he went to Jozelina’s grave and closed his eyes. He said a prayer in silence.

Translated by Kim M. Hastings.

Ronaldo Wrobel is a writer and lawyer born and based in Rio de Janeiro. He is the author of the story collection A raiz quadrada (‘Square Root’, 2001) and the novels Propósitos do acaso (‘Random Purposes’, 1998) and Traduzindo Hannah (‘Translating Hannah’, 2010) which has been published or is forthcoming in German, Spanish, French, Italian, Dutch and Israeli editions.

Ronaldo Wrobel is a writer and lawyer born and based in Rio de Janeiro. He is the author of the story collection A raiz quadrada (‘Square Root’, 2001) and the novels Propósitos do acaso (‘Random Purposes’, 1998) and Traduzindo Hannah (‘Translating Hannah’, 2010) which has been published or is forthcoming in German, Spanish, French, Italian, Dutch and Israeli editions.

Author portrait © Alexandre Sant’Anna

Kim M. Hastings studied Brazilian language and literature at Brown University and has a PhD in Spanish and Portuguese from Yale. She has translated fiction by Lúcia Bettencourt, Rubem Fonseca, Rachel Jardim, Marcelo Moutinho, Alberto Mussa and Edgard Telles Ribeiro. Her translation of Ribeiro’s O punho e a renda is published (as His Own Man) by Scribe and Faber & Faber and forthcoming from Other Press.