Mixed-up thinking

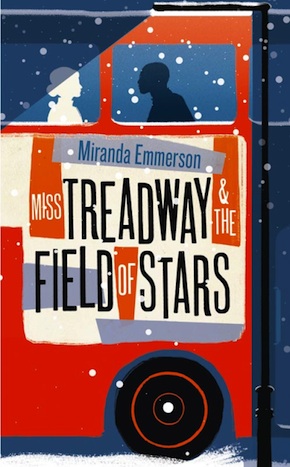

by Miranda EmmersonThis is the story of how I came to write Miss Treadway & the Field of Stars and how it came to be more relevant than even I had imagined. It is a story of two parts – the first a little more obvious than the second. But everything needs a beginning…

My beginning lies in four countries (probably more), but to keep things simple my heritage is English and Welsh and French and Polish. The Welsh part of my family decamped to England two hundred years ago. The French and Polish parts of my family – being Jewish – arrived in London in the 1890s as pogroms swept through Europe and many Jews left the continent for safer countries to the west such as the UK and the US. Though nobody knew it at the time, this action was to save the lives of all who left Poland and create a safer life for those who left France. My husband grew up in Northern Ireland, the child of an Irish mother and an English father: the product of a mixed marriage in a family filled with mixed marriages. Our two children are all these things. Just like millions of other British people they are a grand mixture of religious, ethnic and national traditions.

I moved around a lot in my early years – the child of two actors, as a family we followed work where it took us – but when my parents settled down it was in London and so the world that I knew best was Isleworth (halfway between Richmond and Hounslow in every sense imaginable) in the 1980s and 90s and then, after university, Camberwell in the 2000s. There is a theory that our imaginative universe – the world in which we most readily create – is formed in childhood and early teenage years, and certainly the world I conjure most readily is that world of south and southwest London: families who are English and Irish, Scottish and Welsh, French and Polish and German, Greek and Turkish Cypriot, Indian and Pakistani, Jordanian and Bangladeshi, Burmese and Iranian, Jamaican and Nigerian. Londoners all, British all, but holding within themselves an array of ethnicities, of religions, of influences. My London was and is a melting pot, a city which reflects the multiple identities I hold within myself.

In the winter of 2014–15 we were just gearing up for a general election in the UK. The subject of immigration had been pushed to the forefront of the political agenda by the rise of nationalist parties, the social chaos of ‘austerity measures’ and the dangerously neurotic inheritance of years of anti-black, anti-Muslim, anti-EU rhetoric which are the bread and butter of roughly half our national press. Long before Brexit, long before Trump or the results of the 2015 election I felt the political mood of the country become frightening and hostile and intolerant. As someone who was proud that the UK had offered safe haven to her family in the past, whose mixed identity had long given the lie to ideas of national or religious purity, I felt a flame was being put to many of the parts of Britishness I most admired: her diversity, her status as a nation of incomers and her historic rejection of extremist dogma.

I attempted to engage one angry gentleman in discussion, stating how important an understanding of different cultures and religions had been to my education and development. ‘Britain is white,’ he told me.”

At some point in November I found myself breaking one of my main rules in life: don’t fight with people on the internet. Newspapers had leapt upon the clickbait-happy story of a Cornish school which was daring to use funds to take some of its pupils to Birmingham to see the Diwali celebrations. The story had barely been up two hours when dozens of people had posted their fury – their incredulity – at this profligate, craven, PC move. I attempted to engage one angry gentleman in discussion, stating how important an understanding of different cultures and religions had been to my education and development. “Britain is white,” he told me. “It’s meant to be white. It’s not meant to be Sikh or Hindu or Muslim or anything else like that. That’s not what we grew up with, is it? We’re English. Why are you letting the left-wing papers make you feel guilty because our country looks the way it should?”

I sat and thought about this. Here was this man, sitting somewhere behind his keyboard, who made the assumption that we had both grown up in a world which was white, which was monocultural. I thought about where he might have lived, where he might have gone to school, how it was possible to grow up in a Britain which looked so very different to the one I grew up in. And then I was struck by an urge to illustrate my sense of what it was to be British. I knew that I wasn’t alone. I knew that millions of us are proud – insanely, heart-stoppingly proud – to be British and Polish, British and Irish, British and Indian.

In December – sitting out a fever with my eldest child – a novel came to me fully formed within the space of half an hour. The settings, themes and characters arrayed themselves in my mind and I knew then that I had only to write them down and my first novel would exist. I sat and wrote furiously for twelve weeks – more joyfully than furiously in truth – and at the end of March I had a first draft of Miss Treadway & the Field of Stars.

I wrote about the London that I knew, the London of incomers – American, Irish, German, Polish, Turkish Cypriot and Jamaican. I wrote about a London of Christians and Muslims and Jews. And I tried not to sugarcoat anything; I didn’t want to make it a rainbow-coloured paradise, I wanted to tell the truth. So there is racism, prejudice, homophobia and sexism. Society is crippled by concerns of class and wealth and social acceptability. As Leonard Fleet (Miss Treadway’s boss, himself the child of immigrants) says to Anna:

“Nothing can ever be too English, can it? Nothing can ever be too pure. It’s like there’s an entry test for Englishness and only twenty people pass it every year. Are you clever? Are you virtuous? Are you kind? It doesn’t fucking matter. All that matters is that you’re English.”

I tried to write a London that I recognised, warts and all, and in doing so to represent the reality of a Britain that seemed to have got lost in all that defensive, nationalist posturing.

I have moments – I think we all have moments – of thinking what’s the bloody point? They want us to live in bunkers, to live in segregation? Fine. I’ll build a sodding sofa fort and eat canned food for twenty years.”

That is the first part of the story, the part about how Miss Treadway came to be. But then, of course, the general election came and went with both major parties intoning their worries over rising immigration. Brexit happened and took with it so many things that made me proud to be British: to be British and a European. Trump was elected in America on a wave of nativism and racism but mostly economic fear. And here we are – two years on – my book is out and the world looks so much bleaker even than it did in 2014. I have moments – I think we all have moments – of thinking what’s the bloody point? They want us to live in bunkers, to live in segregation? Fine. I’ll build a sodding sofa fort and eat canned food for twenty years and tell my kids what life was like when trying to make society more equal was still something we thought we could achieve; when casting off the racist, homophobic language of the past wasn’t dismissed as PC bullshit or playing at being a snowflake.

But we don’t really want to surrender; do we? Because the world outside our sofa fort won’t get better, it won’t even stay the same. It’ll get worse out there. Less tolerant. More fearful. Less equal. And ever more divorced from reality. We rankle and worry at the thought of Us vs Them politics, but then we fall into the same trap. Bad people voted for Brexit. Bad people voted for Trump. We are good people and we are sad. We are good people and we are angry. The truth – inevitably – is more complex and more uncomfortable.

This is from Carmen Fishwick’s interviews with Leave voters from the English Midlands explaining why they voted for Brexit:

“Visiting London in 2014 there were no signs of a recession. The city has alienated itself from the rest of England. It felt obscene… The biggest issues are feeling connected, or rather disconnected, in society. The majority are probably the people who have the smallest voice, but who rely on others to advocate for them.”

This is from one of Gary Younge’s reports about the complaints of the white working-class in the Indiana who voted for Trump:

“There is systemic racism but black people have advocates. Poor white people don’t. They’re afraid that they’re stupid. They don’t feel racist, they don’t feel sexist, they don’t want to offend people or say the wrong thing. But for them white privilege is like a blessing and a curse if you’re poor. The whole idea pisses poor white people off because they’ve never experienced it on a level that they understand.”

And then I thought about how I felt when I heard the place of immigrant Britons denied or reviled: I don’t belong here. I’m not wanted. My friends aren’t wanted. We used to belong here. Maybe we never had a proper place at all. My black and Asian friends – their children – are less safe today than they were ten years ago. Racist attacks are getting worse. Anti-Semitic and Islamophobic attacks are on the rise. Maybe it’s time to try another country.

All the views expressed above are real and important. Because there is more than one way to become disenfranchised. There is more than one way to find your voice is silenced. And – yes – inevitably a huge component in all of this is economic. The wage gap grows each year, social mobility grinds to a halt, the public services that make daily living bearable are starved of resources, power and wealth are concentrated in ever fewer hands: mostly in the cities, mostly in London. But economics doesn’t exist in isolation. This is social. This is cultural. This is about a country – a succession of countries – who forgot to tell the stories of the dispossessed. Who failed to realise that if you starve a group of their stories – be they immigrant Londoners or white working-class northerners or the former mine workers of South Wales – you don’t merely weaken that group’s sense of their own reality to themselves. You don’t merely sap whole regions and demographics of their sense of history, their sense of belonging. You also weaken their importance in the eyes of those who distribute funds, who legislate for jobs and services. Failure to tell the stories of a people or a place becomes akin to starving that group of water and of oxygen, of slowly drawing their reality away from them.

This is a moment to tell stories and we need to think very carefully about which stories we are going to tell.

Miranda Emmerson is a playwright and author living in Wales. She has written numerous drama adaptations for BBC Radio 4 as well as highly acclaimed original dramas. Miss Treadway & the Field of Stars, her first novel, is published by Fourth Estate.

Miranda Emmerson is a playwright and author living in Wales. She has written numerous drama adaptations for BBC Radio 4 as well as highly acclaimed original dramas. Miss Treadway & the Field of Stars, her first novel, is published by Fourth Estate.

Read more.

miranda-emmerson.squarespace.com

@MirandaEmmerson

Author portrait © Rebecca Brain