Mudlarking for mannerisms

by Claire McGlasson

It’s I Spy meets solitaire: a solo diversion that helps to pass the time in doctors’ waiting rooms and tedious meetings. I’ve done it in train carriages and post office queues; sitting on an undersized plastic chair before the curtain rises on a school nativity play. I thought everyone did. But I’ve come to understand that it’s A Writer Thing.

While most people might eavesdrop the strained conversation of the couple at the next table, they don’t necessarily imagine the inciting incident that sparked the argument, or speculate whether it will be resolved with a devastating break-up or passionate make-up. They don’t automatically wonder who the two parties might be, how they came to meet, what secrets they might be hiding from the other. But you can bet the writers in the room have noticed the man at the bar who looks up expectantly every time a woman walks in. The one who’s wearing stonewashed denim and keeps buttoning and unbuttoning the collar of his designer shirt. Writers will steal surreptitious glances before concluding that he is recently divorced and newly dating; trying on a new personality like a child might play dress-up.

Hoarding mannerisms, we create a mental archive of facial expressions and turns of phrase. We analyse body language and memorise tics for the next time we create a fictional character by curating a selection of handpicked details.

When I was writing the protagonist of my latest novel, The Misadventures of Margaret Finch, it wasn’t much of an imaginative leap to describe her methods. Working undercover in 1930s Blackpool, Margaret gathers data about working-class families who’ve travelled not a few dozen miles from the mill towns of the North West to holiday by the sea. Though she is invented, the Mass Observation project was real. Posh London types really did spy on “the lower orders” to “record every aspect of life: from talking to sleeping, fighting to drinking, dreams to hysteria.” This took the form of very specific questions. How long, on average, did it take a man to drink a pint? How many young women would forgo the wearing of stockings on the beach in hot weather?

One of the founders of Mass Observation, anthropologist Tom Harrisson, said he had “studied the cannibals of Borneo” and now wished to “study the cannibals of England.” His researchers lived in guesthouses, drank in pubs, prayed in church and crept under the pier to catch couples locked in illicit communion.

Friendliness is a trait I take pride in. But I’m starting to question my motivation, to wonder how the people I’m watching would feel if they knew I was borrowing a part of their personality for a future novel.”

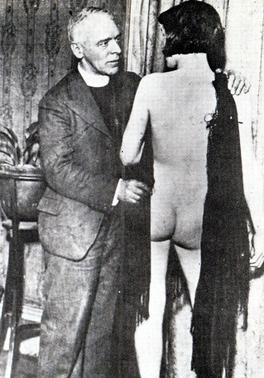

In the novel, I imagine the phenomenon of Mass Observation colliding with another eccentric chapter of British history. In it, Margaret crosses paths with Harold Davidson, known as the Rector of Stiffkey, who was defrocked by the Church after accusations of improper conduct with prostitutes. He became a cause célèbre; a man so famous that his scandals kept even Hitler off the front pages. In real life he went to Blackpool, exhibiting himself in the sideshows to protest his innocence. And in my fictional story he becomes the subject of Margaret’s surveillance.

After reading The Misadventures… writer friends confided that they felt an affinity with Margaret. They admitted that they too are Watchers. While other passengers tut at the boasting man speaking loudly on his mobile phone in the quiet carriage, one told me she’s grateful to be able to sit back and enjoy the show. Another collects unusual names like pinned butterflies – a treasure trove of choices she can dip into whenever she brings a character into being.

Does this habit develop as a result of our becoming writers, or as a precursor to it? I couldn’t say with any certainty. Anyone who lives with the constant fear of discrimination or unwanted attention is likely to be scanning any environment (and more specifically, the people in it) as a precaution. Margaret Finch approaches life as a series of mathematical calculations: “Like every other woman, she makes thousands of these assessments every day: the result of a particular meal on her figure, the probability that the group of men on the street corner might jeer or attack.” As humans, we develop this watchfulness in order to moderate our own behaviour and avoid conflict. It’s a skill that arises from the evolutionary necessity of self-preservation.

Members of my family find it amusing that strangers will often strike up a conversation with me. I’m a magnet for every random stranger and chatty Cathy who is queuing behind me at the supermarket checkout. When it’s my turn to pay I greet the cashier with a “Hi, how are you?” genuinely hoping they might give me an honest answer, and for some reason they often do. Friendliness is a trait I take pride in. But I’m starting to question my motivation, to wonder whether it’s really any different from Mass Observation’s surveillance, and how the people I’m watching would feel if they knew I was borrowing a part of their personality for a future novel.

Unlike the Blackpool researchers, I do not use a stopwatch or spy camera and I don’t carry a notepad and pen (though I know several novelists who do). While Mass Observation looked for patterns, my antennae are usually primed for the exceptional or remarkable. The 1930s researchers looked deliberately and specifically for data, but I am much more random in my sampling. To use another analogy – theirs was the equivalent of a comprehensive archaeological excavation and mine is more like mudlarking: keeping an eye out for anything interesting I might find. Unconscious of the fact I’m doing it most of the time. I’m not sure I’d call it a compulsion but it has certainly become second nature. Most of the stories I imagine will never make it onto the page, but perhaps it’s my brain’s way of keeping the writing muscle flexed for when I next begin a piece of work.

Mass Observation was concerned with the What, When, Where and How of behaviour, but as a writer I am always more interested in the Why. Reading the room may be common, even necessary. But writing the room? That’s another story.

—

Claire McGlasson grew up near Biggleswade in Bedfordshire and studied English at the University of Leicester. She began her career writing for local newspapers and magazines then moved to ITV News where she has worked as a producer, newsreader, weather presenter and correspondent in the Anglia newsroom. She now teaches Creative Writing at the Institute of Continuing Education at the University of Cambridge and offers private mentoring and editing services to emerging writers. The Misadventures of Margaret Finch, her second novel, is published by Faber & Faber.

Read more

clairemcglasson.co.uk

@ClaireMcGlasson

@FaberBooks

Author photo by Jeff Cottenden