Riots, rhymes and reason

by Linton Kwesi Johnson

I am often asked why I started to write poetry. The answer is that my motivation sprang from a visceral need to creatively articulate the experiences of the black youth of my generation, coming of age in a racist society. Some of my early work dealt with fratricidal violence and internecine warfare, not too dissimilar to the mindless gang warfare of today. Back in those early days when I began my apprenticeship as a poet, I also tried to voice our anger, spirit of defiance and resistance in a Jamaican poetic idiom.

Forty years ago, in 1972, I wrote a poem of resistance titled ‘All Wi Doin is Defendin’ in which I said “all oppreshan can do is bring/ pashan to di heights of erupshan/ an songs af fire we will sing/ … sen fi di riot squad quick/ cause wi runnin wile/ wi bittah like bile.” A year later, in 1973, in a poem called ‘Time Come’ I wrote, “fruit soon ripe fi tek wi bite/ strength soon come fi wi fling wi might/ it soon come/ look out look out look out! … it too late now I did warn yu.” Those were the prevailing sentiments of many young black people back then, because of our everyday experience of racism in general and racist police oppression in particular.

After the carnival riots of 1976 and 1977 in Notting Hill, the Bristol riots of 1980 and the uprisings of 1981 and 1985, some people began to say that my early seventies verse was prophetic. I don’t know about that; what I do know is that if you were a young black person in the early 1970s living in urban Britain, you did not have to be prescient to know that sooner or later the police would ignite an explosion. I wrote two poems about the eighty-one uprisings: ‘Di Great Insohreckshan’ and ‘Mekin Histri’. I wrote ‘Di Great Insohreckshan’ from the perspective of those who had taken part in the Brixton riots. The tone of the poem is celebratory because I wanted to capture the mood of exhilaration felt by black people at the time.

And what a time it was! It was a time of intense class warfare. The Thatcher-led government had set in motion policies designed to claw back the gains the working class had won in the post-World War Two settlement. The labour movement was fighting back. The black working class was involved in those struggles. There were autonomous organisations like the Black Parents Movement, The Black Youth Movement, The Race Today Collective and the Bradford Black Collective struggling for racial equality, social justice and radical change. Every institution of the state was riddled with racism and none more so than the police. The gutter press fanned the flames of racial hatred. Racist and fascist attacks against black and Asian people were rampant. The most horrific incident was the New Cross fire on 18 January 1981, the result of an arson attack on a party which resulted in the deaths of thirteen young black people, with twenty-six suffering serious injury.

It was the most spectacular expression of black political power ever seen in this country; a watershed moment in our struggle for racial equality and social justice… We were the rebel generation, a politicised generation and we were fighting back.”

The response of the black communities to that atrocity and the attempt by the police to cover up the truth and frame some of the partygoers for the fire, was the mobilisation of 20,000 people by the New Cross Massacre Action Committee, chaired by John La Rose, for a march from New Cross to Hyde Park to protest the deaths of those young people and to demand justice. It was the most spectacular expression of black political power ever seen in this country; a watershed moment in our struggle for racial equality and social justice. That march, on 2 March 1981, known as the Black People’s Day of Action, gave black people up and down the country a new sense of our power to resist racial oppression and to fight for change. It became clear for all to see that second- and third-generation black people – my generation – were no longer prepared to endure what our parents had. We were the rebel generation, a politicised generation and we were fighting back. One month later, in April, the uprisings began in Brixton.

On 6 August last summer [2011] when the riots began in Tottenham, I was performing at a reggae festival in Belgium accompanied by the Dennis Bovell Dub Band. Two of the tunes we performed were ‘Di Great Insohreckshan’ and ‘Mekin Histri’. It was quite late when we got to our hotel and we all retired for the night as we had another gig on the Sunday in France. I was in bed when the phone rang. It was Dennis Bovell, a Tottenham resident. He said, “Linton, turn on your TV, riot a gwaan a Tottenham.” I tuned into BBC World and saw Tottenham burning. The television set in the cheap hotel where we stayed in France the Sunday did not have BBC World, Sky or CNN but Dennis Bovell received quite a few text messages and we were kept up to date with was happening. I thought everything would have calmed down by the time I arrived back in London, only to discover that the riots had intensified and had spread to towns and cities all over England.

Some of the scenes I saw on the television were unbelievable. What was most astonishing was that the police seemed powerless to act. It seemed as though they were working to rule or taking some kind of unofficial industrial action. It is not as though they were inexperienced dealing with riots. It seemed to me at the time like a blatant dereliction of duty. I was not at all surprised that the riots began in Tottenham in the light of the cold-blooded killing of Mark Duggan by a police officer, the misinformation put out by the Independent Police Complaints Commission, and the history of conflict between the police and the black community in that part of London. Given the continuing deaths of black people at the hands of the police or in police custody, the criminalisation of young black people, the disproportionate use of stop and search against black people, the charge of joint enterprise and the marginalisation and demonisation of sections of the working class, black and white, a riot was just waiting to happen. What did surprise me was the ubiquity of the riots.

To my mind, faced with the prospect of a twenty per cent cut in their budget, the police wanted to make a point to the government. It was as though they were saying to Chancellor of the Exchequer and the Home Secretary, “this is what could happen if our manpower is reduced.”

What was most astonishing was that the police seemed powerless to act. It seemed as though they were working to rule or taking some kind of unofficial industrial action.”

Soon after I got home from France, I received requests from national newspapers in Belgium, France, Russia and the USA for comments on the riots. I declined because I surmised that if they wanted to speak to me, it would be to portray the riots in purely racial terms. It is clear to me that the causes of the riots are racial oppression and racial injustice, as well as class oppression and social injustice. The most widespread expression of discontent that I have ever witnessed in this country has to be seen in the context of the marginalisation of sections of the working class and the ideologically driven austerity measures of the Tory-led government. The police have done little or nothing to eradicate racism from the way they carry out their duties. The rank and file never accepted the findings of the Macpherson inquiry into the murder of black teenager Stephen Lawrence in 1993 in south-east London that stated that they are institutionally racist. My grandson has lost count of the number of times he has been stopped and searched by the police and he’s not a gang member. As far as policing and young black people are concerned, nothing has changed since I was a youth, nothing has changed since the uprisings of 1981. Never mind what Trevor Phillips says.

However, black people as a whole have made significant advances since the end of the 1980s. We are no longer as marginalised as we were in 1981. We had to resort to insurrection to integrate ourselves into British society. As the late John La Rose observed nearly a decade ago, black people are now very much inside British society; we are no longer on the periphery. Yet, after the progress of the nineties and early noughties, there is a perception amongst some black people that we have reached the glass ceiling and racial equality is no longer on the agenda of New Labour, the Tories and Liberal Democrats. In fact the budget of the Equality and Human Rights Commission has been cut by 63 per cent. People like Professor Gus John, for example, rightly continue to critique the educational system for failing black working-class children. Recent government statistics show that the unemployment rate for young black people is now over 55 per cent. Just as black Christians had to start their own churches many years ago, so black police officers have had to form their own staff association as the police force is still pathologically racist.

Joseph Harker of the Guardian rightly observes that the dozen or so black Members of Parliament are one step removed from their communities. It was churlish of Simon Woolley from Operation Black Vote to accuse him of nostalgia. There is no evidence that our black MPs, having reached where they are now, will champion the case of racial equality or campaign against racist police practices. The onus is still on our communities.

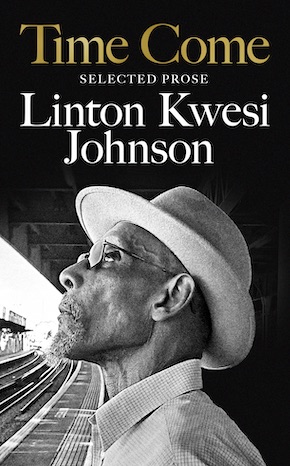

Local Brixton speech, 24 March 2012. Reproduced with permission from Time Come: Selected Prose (Picador, £20).

—

Linton Kwesi Johnson is a Jamaican-born reggae poet who came to the UK in 1963. Joining the Black Panthers whilst still at school, he has been a life-long activist fighting for racial equality and social justice. In 2002 he became the second living poet, and the only black poet, to be published in the Penguin Modern Classics series. He has recorded several albums, many on his own LKJ Records label, and has toured the globe. His most recent awards include the 2020 PEN Pinter Prize and, in 2021, being appointed an Honorary Doctor of Letters by the University of the West Indies. He lives in Brixton in south London. Time Come is published by Picador in hardback, eBook and audio download.

Read more

lintonkwesijohnson.com

@picadorbooks

Author photo by Ajamu Ikwe-Tyehimba