Orlando Ortega-Medina: Love without borders

by Brett Marie

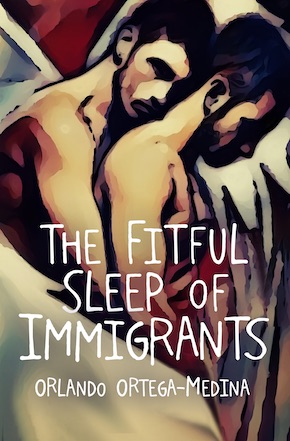

Orlando Ortega-Medina’s riveting novel The Fitful Sleep of Immigrants wears its politics on its sleeve. Beyond the inclusion of the perennially hot-button word Immigrants in its title, one needs only to peel back the front cover and read the dedication to find the first direct iteration of its author’s message:

“To the countless multinational same-sex couples forced to emigrate due to marriage inequality and to those progressive countries that welcomed them with open hearts.”

In novelising his advocacy for equal rights, Ortega-Medina follows a long tradition in American literature. If at times the United States can seem a nation exceptionally beset by social ills, it has throughout its tumultuous history gained a measure of redemption through the authors who have used fiction to shine a light on its evils. What Dalton Trumbo’s Johnny Got His Gun accomplished for the anti-Vietnam War movement, John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath did for migrant workers on California farms during the Great Depression. Further back you’ll find Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle decrying the horrific excesses of the American meatpacking industry at the turn of the twentieth century. And let’s not forget the grandmother of them all, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which helped tip Northern public opinion against slavery in the run-up to the Civil War.

A London-based attorney specialising in US immigration law, Ortega-Medina is well equipped to join these activist authors and argue his particular case. His intimate understanding of the gears and mechanisms of the American legal system renders painfully real the plight of Marc and Isaac, a San Francisco couple whose home life is thrown into chaos when Isaac, a Salvadoran immigrant, has his legal status suddenly revoked. Threatened with Isaac’s deportation, the two are forced to run a labyrinthine gauntlet of hearings and legal motions in a long-shot bid to stay in the US. Recounting the process through the eyes of Marc, himself a successful lawyer, Ortega-Medina keeps the proceedings unsensational. He wisely recognises that the real drama to be mined comes from Marc’s keen sense of injustice at their situation: Isaac’s status wouldn’t be an issue if the two were married, but this is the 1990s, more than a decade before the US Supreme Court ruled same-sex marriage constitutional.

Marc’s anger and dismay as he eyes the axe hovering over the life he and Isaac have built together feels vivid, authentic – and well it should. The author’s empathy for his protagonist comes from far more than professional experience. “Marc is me for the most part,” Ortega-Medina tells me in an email interview. “In a nutshell, when I met my partner, he was living in the United States on a grant of Temporary Protected Status (TPS), having fled the danger of El Salvador’s civil war. Once that war ended, the US government started the process of deporting people like my partner back to El Salvador, unless they’d found a way to regularize their status, such as by marrying a US citizen. However, this option was not available to same-sex couples in the 1990s.”

Internalized homophobia is the natural result of living within a societal regime that is constantly signalling that you are not acceptable as you are. You’re a sinner, you’re a pervert, you’re mentally ill…”

The nineties setting colours the novel with more than just legal technicalities. For all of Marc’s material success in the book’s opening pages, he faces constant subtle and not-so-subtle signals, from both his family and the wider world, that he doesn’t belong. The world seems to be telling him that there are things about him and his partner – things that are both immutable and intrinsic to who they are – which disqualify them from the lives they’ve made and the communities they inhabit.

I muse to Ortega-Medina about the effect this kind of signalling might have on a gay man. His answer is as insightful as it is heartbreaking. “Different people react differently, depending on how they’re wired.” He goes on to enumerate the different actions and attitudes of the novel’s main gay characters: running, hiding, scheming, denying. “These are all examples of internalized homophobia, which I believe is the natural result of living within a societal regime that is constantly signalling that you are not acceptable as you are. You’re a sinner, you’re a pervert, you’re mentally ill… imagine absorbing this type of messaging all your life. It becomes part of one’s identity, whether one likes it or not.”

The pervasive homophobia of the time affects even Marc’s family, including his rabbinical judge father, who must navigate between his intense faith and his natural familial devotion to reach a point of accepting his son for who he is. Ortega-Medina is adept at creating an honest and relatable family dynamic, and indeed one of the novel’s great strengths overall is its even-handed portrayal of the characters close to Marc. Watching all of these loved ones get over their pre-conditioning and come through for Marc, each in their own way, it’s easy for a reader to share Marc’s sadness that he will have to let them go.

And Ortega-Medina’s love extends beyond his human cast. Poignantly, in some of the author’s most evocative passages, the city of San Francisco itself becomes yet another character Marc must grapple with leaving behind.

“As we reached the T-intersection of Broadway at the Embarcadero and waited for the crosswalk signal, the lights of Pier 7 caught my attention. It had been a long time since I’d walked on the old, wooden pier. When the signal changed, I crossed the street and headed to the far end of the pier, which was spottily illuminated by some old-fashioned streetlamps. It was peaceful there, the stillness broken only by the gentle lapping of water against the pilings and the distant hum of traffic. I leaned against the black wrought-iron railing and gazed across the water at Yerba Buena Island, a large heap of rocks and trees looming in the dark with the glittering San Francisco span of the Bay Bridge thrust into it. I lost myself in the view, blocking out all extraneous sights, sounds, and thoughts. As I watched the waters of the bay splash against the rocks and relished the cool, salty breeze rustling my hair, I felt the elusive sensation of absolute calm.”

Here and elsewhere, the urban landscape Ortega-Medina paints is so vibrant, so up-close, that at times you can feel the city breathing.

The novel’s legal drama builds as the wheels of American bureaucracy grind toward Isaac’s inevitable deportation. Ortega-Medina’s reality was different. “Rather than sit around waiting for a deportation notice to arrive, my partner and I proactively sought out a country that would offer us the liberty and respect denied us as a couple in the USA. That country was Canada, where we were welcomed with open arms in August 1999.”

In fact it was in Canada that the couple’s real-life drama, and his motivation to write on the subject, began in earnest. “I’d never felt freer in my entire life as we went about setting ourselves up in our new country. I was delighted to find the fact we were a gay couple was a non-issue for anyone we met. As I embraced that reality, I felt as if a heavy weight had been lifted off my back. Nevertheless, there was a sting in the sweetness of those early days. There was no denying we were starting from scratch: no home, no jobs, no recognized credentials, no friends, and no family. My partner coped better with this, focusing on the positive as he helped set up our new home. I, however, experienced a crisis of identity. I’d gone overnight from running my own thriving law practice to working temp jobs in Toronto law offices, resentful I’d been relegated to making photocopies and serving coffee. Honestly, I felt terrible. And it was in this state of mind that I started work on a memoir documenting what we were going through. Working on that memoir, though, made me feel worse, as if I were reliving everything all over again.”

Dogged by this bitterness, Ortega-Medina did what he had to do, for his psyche and his book. “I set it aside and focused instead on reinventing myself as a US immigration lawyer, which was the best decision I ever made. Years later, when I’d enough distance on the subject, after having honed my writing chops on two prior novels, I felt ready to re-approach the material from a better mental space – as a novel, not as a memoir.”

Leaving memoir behind, Ortega-Medina makes use of the liberties of fiction, while being careful in portraying aspects of Marc’s life which don’t track with his experience. Foremost among the differences between the author and his protagonist: a history of addiction, which Marc must keep in check to maintain the stable, affluent life he enjoys.

“I’m not a recovering addict myself,” Ortega-Medina tells me. “But I’ve had close relationships with people, including partners, who’ve struggled with different types of addictions, including gambling addictions, sex addictions, and substance addictions. I drew on my personal experiences with those individuals when working out Marc’s character in later drafts of the novel. I also took advice from a trusted beta reader with relevant insider experience regarding this aspect of Marc’s personality to ensure his authenticity. This last step is critical, I think, for a writer who dares to approach this delicate subject but who doesn’t have personal experience with addiction.”

His approach pays off handsomely. Marc’s eventual descent into drinking, his pathetic attempts to hide his lapse from Isaac, and his struggle to climb back on the wagon, follows an unnervingly familiar path which will put a knot in the stomach of anyone who knows addiction. It is another deft act to connect and interweave this downward spiral with that of Marc’s legal woes.

I didn’t set out to write a thriller! What I had at the very beginning were, in effect, three separate stories, each very different from the others with Marc being the only common denominator.”

And then there’s the character of Alejandro Silva, a former client who weasels his way into Marc’s personal life and begins to sow chaos. Silva fits a template that fans of the thriller genre will recognise: the possessive stalker who won’t let go. Exploiting his and Marc’s mutual animal attraction, preying on Marc’s weaknesses, Silva sets about driving a wedge between Marc and Isaac so that he can possess Marc for himself. And as effective as Silva’s constant lurking is in piling on Marc’s dismay, as horrifying as the damage he causes is, Silva blows up Marc’s life with such flair that I have to assume Ortega-Medina had at least some fun dreaming up the carnage.

Did he enjoy writing a thriller? I ask. “I didn’t set out to write a thriller! (Sorry!) What I had at the very beginning were, in effect, three separate stories, each very different from the others with Marc being the only common denominator: Marc and Isaac; Marc and his family; Marc and his legal practice. The task I took upon myself, for my sins, was to interweave these three stories into a single novel, and then to weave them ever tighter with each successive draft, defining and refining the characters along the way. What I ended up with was what my publisher describes as ‘a powerful family drama that plays out within a captivating legal thriller.’ As for Alejandro, whom I originally cast as a homophobic killer rather than a charming grifter, once I hit my stride with him, I enjoyed dreaming up ways for him to slither his way into Marc’s life. He became the novel’s snake in the garden, ‘the most subtle beast of the field.’”

The novel’s thriller element certainly turns pages, but the realities of its era are its real source of darkness. When discussing how society has evolved in the past quarter century, Ortega-Medina is guarded in his optimism. “I’d like to believe that the signalling has improved since the nineties. But I suspect that all depends on where you live or the type of household you grow up in. LGBTQ+ people are still being attacked on the streets in 2023, even in San Francisco. As far as I am aware, nobody is being attacked on the streets in any US city simply for being heterosexual.”

Considering this state of affairs, Ortega-Medina’s view of his country of origin are understandably nuanced. “These days I’m often asked whether we’d ever consider moving back to the United States now that marriage equality is the law of the land. My answer to this question is a resounding no. Although I count myself as a proud American expat and enjoy our annual visits to California to reunite with our families, once my partner and I tasted life outside the United States, including the liberal social policies we sought, there was no going back for us.

“There’s still a long way to go before we who are LGBTQ+ are on equal footing with everyone else, given that close to 50% of the US population still considers us to be counterculture. Along our journey, we’ve encountered several other couples with similar stories, and it is to them that I have dedicated The Fitful Sleep of Immigrants. I’m hopeful that my book, as a crossover novel, may engender some empathy for our cause and help swing the pendulum of public opinion a bit more to our side.”

Just how far can a novel push that pendulum? Upon meeting Harriet Beecher Stowe, while his Union army fought the Confederacy over the issue of slavery, Abraham Lincoln joked, “So this is the little lady who started this great war.” Quips aside, it’s impossible to know just how great an effect one work of fiction can have on the course of history. But politics, at its core, is about people, and one of the great strengths of written fiction lies in its ability to make a reader see and feel other people’s perspectives from the inside. And though Ortega-Medina’s issue of choice ought to have been resolved with the Supreme Court’s Obergefell v. Hodges decision of 2015, readers who have watched the recent actions of an increasingly conservative-reactionary court will recognise that none of liberal America’s legal victories is set in stone. Before reading The Fitful Sleep of Immigrants, such thoughts simply troubled me. Now, having lived Marc’s life for 300 pages, I’m ready to sign a petition, join a march, pull a lever. In this way the pendulum swings toward justice, one reader at a time.

—

Orlando Ortega-Medina was born in Los Angeles to Cuban immigrants. He studied English Literature at UCLA and holds a Juris Doctor from Southwestern University School of Law. In 1999, Ortega-Medina and his partner expatriated to Canada, where they were among the first same-sex couples to marry at Montreal’s Hotel de Ville in 2005. He is the author of three novels and a short story collection shortlisted for the UK’s Polari First Book Prize. In 2018, he was named the Marilyn Hassid Emerging Author for the Houston Jewish Book & Arts Festival. Ortega-Medina and his partner now live in London, where he practises US immigration law and writes fiction. The Fitful Sleep of Immigrants is published in paperback and eBook by Bywater Books.

Read more

orlandoortegamedina.co.uk

@oortegamedina

@BywaterBooks

Brett Marie, also known as Mat Treiber, grew up in Montreal with an American father and a British mother and currently lives in Herefordshire. His short stories and other writing have appeared in publications including The New Plains Review, The Impressment Gang, Pop Matters and Bookanista, where he is a contributing editor. His debut novel The Upsetter Blog is published by Owl Canyon Press.

Read more

@owlcanyonpress

Facebook: Brett Marie

@brettmarie1979

bookanista.com/author/brett-marie/