My mother’s war

by Cécile Desprairies

DRIVING HER 2CV BACK TO PARIS through the gloomy forests of the Oise, Lucie imagined the dialogue at her trial:

“Have you ever been a Nazi?”

“Of course! I was a very happy Nazi.”

“You really were a Nazi?”

“Why not?”

“Do you know, you are the very first person we have ever heard confess to it.”

Lucie imagined the entire courtroom staring at her and burst out laughing. Saved from prison on grounds of honesty and loyalty.

—

Sometimes my mother would be overwhelmed with sadness after saying goodbye to her little girl. Unable to see through her tears, she would pull over onto a grassy stretch along the road, switch off the engine, and cry her eyes out. Everything was mixed up in her head. It was so difficult being a mother. So hard to keep going on her own. After a while she pulled herself together, delved into her purse for a handkerchief, then rifled around in the glove compartment, finding the piece of chamois leather that had come in handy during the war to filter fuel from German planes, eventually laying hands on a cloth handkerchief, which she used to dab the tear stains off her face in the rearview mirror. Then, chin down, hairpins clamped between her lips, she looped a headscarf around her chignon, knotted it at the nape of her neck, scraped a little lipstick onto her lips from the very bottom of the tube – the treasures in the little car’s glove compartment were apparently inexhaustible – and grimaced into the rearview mirror to make sure there was none on her teeth. Finally, she dabbed some more lipstick onto her cheekbones and checked her face in the mirror one last time. She was ready to go. She pulled out the choke, then listened to the engine resist for a moment until it started with a cough. She maneuvered the car off the roadside and back onto the pavement. It was the same Citroën 2CV – the French version of the Volkswagen Beetle, the “people’s car” commissioned by the Führer in 1938 – she had been driving since the early 1950s. To Lucie, it was a mythical object, the receptacle of all her brooding aspirations. A lifetime vehicle: the only car she ever drove. It was nicknamed in France the walnut shell, the nuns’ car, deudeuche. No other car would have suited her. She paid so little attention to the rules of the road that it was only the sluggishness of the engine that kept her safe.

As night began to fall, she switched on the headlights. It was what Friedrich used to call “the witching hour.” She leaned over the steering wheel and scanned the road. It reminded her of the blackout. Soon it would be pitch-black, the road ahead lit only by the car’s pale-yellow headlights. She resumed her monologue, locked in her memories, on the verge of madness.

It was not as if she lacked support. There was her family, the inner circle, the gynaeceum, who clung to her like mollusks to a rock. They constituted the framework of her life – though they sometimes felt like a millstone around her neck. They had the merit of being there, like pieces of furniture, part of the décor, protectors of memory. They had gone through the same experiences, shared that world with her, part of the happy few who had known it. She was the queen bee, and her hive was more or less under control. They knew one another so well.

There were her former in-laws, Friedrich’s family, that of her first, eternal, true husband. Lucie remained in contact with Friedrich’s sister throughout their lives, her faithful ally, with her proudly assumed and unwavering Nazi convictions. When she was twenty-nine, clad in a dark suit rather like those worn during the Occupation by the women known as the souris grises – gray-suited young French women who worked as secretaries for the German occupying army – she married a pale man, a little head-in-the-clouds, so lackluster it was almost as if he had already ascended to heaven. This was in 1950, six years after Friedrich’s death, and his stern-featured sister still carried herself as if she were her brother’s widow. She continued to carry the torch, the true Nazi of the family, increasingly indifferent to everything else.

It was not so long ago that mothers were giving their sons to the Führer, but all the same, Lucie was a little shaken by how hard her sister-in-law had become.

Then there were Lucie’s other in-laws, from her marriage to Charles. They simply generated unplumbed levels of boredom. Apart from her cousins’ children, who had not – or not yet – become bourgeois, petty, and noxious, being with them was an endless round of empty chatter and tedious anecdotes sprung from narrow provincial minds. Her authoritarian mother-in-law, whom Lucie always addressed as Madame, was unsettled by this daughter-in-law who refused to bow to convention. Brisk, efficient, bordering on rude, Lucie found it hard to disguise her impatience at the disordered way of thinking wrought by Catholic bigotry. Even their antisemitism was pathetic. No genuine ideology. At least Lucie’s antisemitism was bold. Her manners horrified her husband’s family, though they politely put it down to eccentricity. Oh, Lu-cie…

No, she had no regrets. On the contrary. If all the French had been on the right side, Germany would have won the war. You only had to look at what a prosperous country Germany had become once more.”

From time to time, as the years went by, Lucie looked back on her life. She had worn so many masks that had both helped and hindered her, methodically erasing past lives when they no longer suited her current reality. But for decades now, her life had followed a straight and narrow path, and she permitted herself the occasional affair simply to make life more bearable.

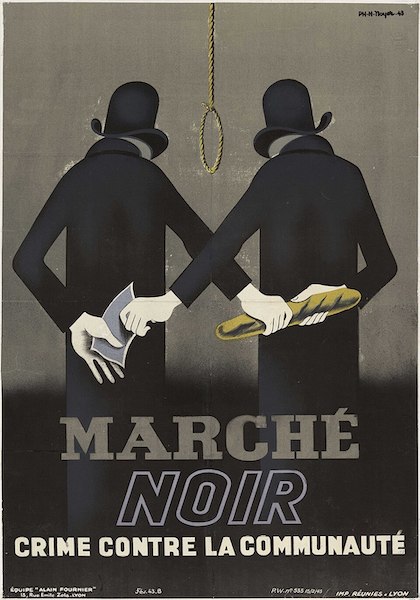

As for the horrors of the last war, well, they must have done something to deserve it, no? She hated the ghastly expression “war profiteers.” Everyone knew that the apartment on the Place des Pyramides had been vacant when she and Friedrich moved in, but it had been the tenant’s choice to move out, and he had had the means. How was that Lucie’s fault? The couple had been looking for a place to settle down. It wasn’t as if she had posted a classified advertisement: “Couple looking to purloin an apartment.” And when you think how hard she had worked! She deserved a suitable recompense. Their apartment on Place des Pyramides – aptly named – and the one on Quai de l’Archevêché – an address too religious for their secular family – allocated to her sister’s husband, were both in acknowledgement of services rendered.

Lucie was never very interested in what she called “things.” “They’re just things,” she would say, referring to confiscated property, a term she employed frequently. To justify herself, she bandied about a legal term, “in trust,” which meant “assigned to a person in good faith.” Lucie was very fond of the notion of good faith. Someone gives something to someone else, for them to give to someone else. The real owner is the “community of the people.” This was not yet law in France, but it would be. She also liked to quote the Latin adage Uti possidetis juris, which she thought meant something like “You possess what is already in your possession.” As far as Lucie was concerned, it was always a question of possession.

With extraordinary resourcefulness, she gave to one person, took from another, returned, exchanged, sold, bought back, reallocated, and disposed as she pleased of “things,” her own as well as those of others. Whenever she arrived somewhere new, she would always look around to see what she could leave with or negotiate for. It could just as well have been an article of clothing as an apartment. She always renamed her newly acquired possessions, supposing it might have otherwise been possible to trace them back to their original owners.

No, she had no regrets. On the contrary. If all the French had been on the right side, Germany would have won the war. You only had to look at what a prosperous country Germany had become once more. Friedrich was no longer there, but he would be back. They had to remain unchanged for each another. They had done everything right. This was just a difficult period they had to get through. The Reich would be reborn, in one form or another. Vichy would continue. It was just a dirty trick that history had played on them. Fortunately, there were plenty of people who remained unbowed and unbeaten. As Friedrich, with his habitual touch of pomposity, had once written to Lucie: “We shall stride toward the future, our consciences clear and our heads held high, faithful to our conception of the world and of this life.” Now it was Lucie’s turn to address Friedrich. My honor is my fidelity. Vae victis, woe to the vanquished. History is always written by the victors. And to the victor go the spoils.

“Things” were always perfectly straightforward. It was people who complicated them.

from The Propagandist, translated by Natasha Lehrer (Swift Press, £14.99)

—

Cécile Desprairies is a specialist in Germanic civilization and a historian of the Nazi occupation of France. The author of several historical works about the occupation and the Vichy regime, she was born in Paris in 1957. The Propagandist, her first novel, is based on her own family’s collaboration with German occupying forces, and its lingering aftermath. The French edition was longlisted for the 2023 Prix Goncourt.

Read more

@_SwiftPress

Natasha Lehrer has translated books by Georges Bataille, Robert Desnos, Vivtor Segalen, Chantal Thomas and the Dalai Lama. Her co-translation of Nathalie Léger’s Suite for Barbara Loden won the 2017 Scott Moncrieff Prize.

natashalehrer.com

@NatashaLehrer