Near death – and resurrection

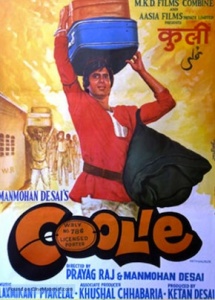

by Sunny SinghOn 25 July 1982, Amitabh Bachchan was injured in Bangalore while shooting for Manmohan Desai’s Coolie (Porter, 1983). The shot required a simulated punch to the star’s abdomen, a fall on a desk, followed by a half-somersault to the other side of the desk. Bachchan refused a body double and shot the sequence himself. The first shot, with actor Puneet Issar, was deemed successful but Bachchan soon complained of pain. Shortly after, the actor was taken to hospital, first in Bangalore, then to Mumbai’s Breach Candy hospital, as his condition mysteriously deteriorated. Doctors finally identified septicaemia as a result of a minor injury. On 2 August 1982, Bachchan was declared clinically dead at the hospital, rapidly revived and was miraculously on the road to recovery. These are the facts at least. Beyond that, real life, film, and stardom collapse into a seamless whole.

Bachchan’s accident marked a moment of mass hysteria in India and abroad, a demonstration of both star power and the influence of a star on public discourse and imagination. As the star lay in hospital, rumours grew, with some accusing Issar of deliberately attacking the star.

Others changed the fifteen-second sequences into a complicated fight sequence in which fists as well as legs were used. The hero’s fall was magnified into a twenty-foot fall. Amitabh Bachchan’s screen presence as the indestructible hero made people think that only an extraordinary event could have led to his injury.1

The mass hysteria was partly fuelled by the media. The hospital instituted a daily bulletin which was carried by the national press. The Times correspondent in India, Trevor Fishlock wrote :

Public prayer meetings were called and people gathered in their thousands to plead for him. Advertising hoardings were rented to carry messages urging the hero to survive… Hospital bulletins on his condition were front-page news every day and newspapers and magazines carried large articles.2

In a real-life imitation of many Bachchan-Desai films, prayers were offered in temples, mosques, churches, and gurudwaras, and crowds thronged outside the hospital for news of their idol. Visitors included the biggest stars of Indian cinema including Zeenat Aman, Shashi Kapoor, and Amjad Khan. Bachchan’s elite connections were very much in evidence as ‘Rajiv Gandhi cut short his American trip to see his friend in hospital on August 5. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, too, made a “purely personal and private” visit’ on 8 August (ibid: 144). All the while, journalists and fans waited for Rekha, the star’s rumoured lover. But she never came.

National media and billboards across the country celebrated the star’s return to work, proclaiming ‘God is Great! Amitabh Lives.’”

Upon his recovery, Bachchan himself added to the filmic narrative:

On August 2 I was declared clinically dead. Jaya had gone to the Sidhi Vinayak temple and she rushed back. Panic-stricken she stood outside the ICU, watching the doctors’ attempts to revive me… apparently in vain. Suddenly she screamed from outside. Don’t give up, I just saw his toe move. Please keep trying. The doctors started massaging my feet upwards. And I came back to life.3

The above passage assembles many of the elements of Bachchan’s blockbuster films: a devoted wife; a trip to the temple; a near miracle when doctors had apparently given up; and in a elision of star and divinity, the ‘massaging of feet’ recalls episodes from the Hindu epics of the care bestowed by humans on deities, with the doctors now reframed as devotees.

Bachchan recovered fully and reported back to the set of Coolie on 7 January 1983. The shooting resumed with the sequence that had been interrupted by his accident. National media and billboards across the country celebrated the star’s return to work, proclaiming “God is Great! Amitabh Lives.”

The amalgamation of the star’s on-screen and real-life experience did not end with his return to acting as the film’s script was amended to include the actor’s near-death experience. Although Desai, as director, “deplored the morbid publicity – ‘publicity not paid for by me’, as he said” he chose to ‘satisfy’ the public.4

In the film, two freeze frames are included to inform the viewer of the punch that caused the injury. Printed on the screen in three languages, English, Hindi, and Urdu, are words that explain: “This is the shot in which Amitabh Bachchan was seriously injured.” Indeed, with this device, “the hero of our time becomes pure simulacrum.”5 Haham is more empathetic, noting that “the intervention of reality in the midst of a screen story might seem an unnecessary distraction, but for the masses of India who had prayed for Amitabh Bachchan’s recovery, Manmohan Desai knew that speculation about the moment would be inevitable.”6

Desai also changed the end of the story, convinced he could no longer present the on-screen death of the star: “He could imagine them cornering him with, ‘Uncle, we prayed and Amitabh Bachchan lived and now you have killed him’”7. Instead a coda was added, showing Hindus, Muslims, Christians, and Sikhs praying for the hero Iqbal’s life, just as they had in reality. Iqbal makes a ‘miraculous’ recovery, just like the star. The final scene shows Bachchan walking onto a balcony below which is a sign, “St Philomena’s Hospital”, a reference to the hospital in Bangalore where the star had initially been treated. He wears symbols of the country’s four major religions around his neck and thanks the cheering throngs for their prayers. In real life too, Bachchan “prayed at each of the centres of worship, giving thanks to all those whose prayers had, it seemed, reached their destinations.”8

1 Vijay Mishra, Bollywood Cinema: Temples of Desire. Routledge, 2002.

2 Cited in Derek Bose, Brand Bollywood: A New Global Entertainment Order. Sage, 2006.

3 Mishra (ibid).

4 Connie Haham, Enchantment of the Mind: Manmohan Desai’s Films. The Lotus Collection, 2006.

5 Mishra (ibid).

6 Haham (ibid).

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

From Amitabh Bachchan (Palgrave/BFI paperback, £16.99)

Author portrait © Walter White

Sunny Singh was born in Varanasi and brought up in various Indian cantonment towns, Islamabad and New York City. She studied at Brandeis University in Waltham, Massachussetts, Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, and the University of Barcelona, and currently teaches Creative Writing at London Metropolitan University. She has published three novels, a non-fiction book on lives of single women in India, numerous short stories and essays. Her latest novel Hotel Arcadia is published by Quartet Books. Amitabh Bachchan is published by Palgrave on behalf of the BFI in paperback and eBook, the latest title in the Film Stars series.

Read more

sunnysingh.net

@sunnysingh_n6

Read Sunny’s Top Ten Amitabh Bachchan films:

Angry young, frail old man