Never a dull word

by Gini AlhadeffIn April 2015 a delightful story by Fleur Jaeggy, ‘The Saltwater House’, appeared in my inbox. As I read it the Italian seemed to turn into English spontaneously in my brain. It had been sent by a friend in Milan to a friend in New York who then forwarded it to me. It was a last addition to I Am the Brother of XX for which an American publisher had yet to be found. It began like this: “On the 31st of July, 1971, we left Rome by car, an Alfa Romeo 2600, for Poveromo-Forte dei Marmi. Ingeborg Bachmann manned the road maps. It seemed like a great voyage, with Poveromo further away than Vienna and Klagenfurt, where we had already been.” Clearly, all of it had happened, though it now breathed the thin air of Jaeggy’s retelling. “But now we were to spend a month together. Already that could be a mental voyage: co-habitation, prefiguring. The house we had rented was vast, with a garden. But the water was salty. Our first pot of tea was disgusting.” The two maids at the house were Jehovah’s Witnesses. One devoutly collected the golden hairpins Ingeborg Bachmann occasionally mislaid on the sofa. “At the head of the table a friend of Ingeborg’s, Roberto Calasso.” He is editor of the fabled Italian publishing house Adelphi, based in Milan. Other mythical figures make their appearance – Joseph Brodsky, Oliver Sacks – though in the story regarding an evening in the latter’s company the real star is undoubtedly a fish in a tank with whom Jaeggy-the-Writer develops a bond. Calvino, too, appears at the saltwater house. He doesn’t speak. Ingeborg and the narrator decide that if he doesn’t speak they won’t either. One night they go out to dinner – an elegant soirée at a German publisher’s house – at the end of which they conclude that they would rather stay at home by themselves. They decide that they will henceforth decline all invitations that might come their way.

What was it like to translate Fleur Jaeggy? Her writing wants to go into English, and does so without putting up much resistance. I’d read her books before, and I’d met her several times, but what I discovered when I started to translate her were a few things I hadn’t known about her. She writes in no clearly detectable national idiom. She writes in Italian, though she is Swiss, and has lived the better part of her life in Italy – or Milan, to be precise. Her Italian is spare as though it were English. She proceeds by images. She never debases her procedures to the demands of a plot. The unstoppable rhythm is given by the weave of small incisive facts chosen for their ability to carry the thread, derail it interestingly, complicating it, to paint in a few swift strokes leaving out mundane detail. There is never a dull word though the words used are frequently ‘normal’, not fussy: in an emergency, the emergency of Jaeggy’s communications, they catapult the story forward in a neat little bound, without seeming to try very hard.

While translating, I’d find a word and sometimes I’d ask, is there a drier word, a more skeletal word, that doesn’t cushion what is there in the Italian?”

There are swamps of facts over which Fleur Jaeggy finds a way to leap. One suspects she might have pored over histories, heard one side and the other, studied the architecture, the interiors, the weather at the time in that place, the tedious accounts of witnesses, the copious descriptions available, regional records, had a good night’s sleep over them, a few hundred sleepless ones, then conjured three lines to calm vast murky seas of information.

While translating, I’d find a word and sometimes I’d ask, is there a drier word, a more skeletal word, that doesn’t cushion what is there in the Italian? “Caspar is taken by nostalgia,” the Italian says. Not overcome, overwhelmed – but taken. Seized, then.

There is some cliff-hanging, not of the who-done-it, but rather of the who-is-it sort. You might know at the end of a piece, which you’ll read without preconceptions or foreknowledge, that it’s Joseph Brosdky, or Oliver Sacks, or Ingeborg Bachman. And what you’ll be left with is the detail of a portrait – the equivalent of the crease of a shirt on an elbow, for instance – but it will be something incontrovertible, that delivers some intimate knowledge of its subject in code.

Jaeggy’s entire art functions by omission. Even the real Fleur Jaeggy doesn’t like revealing herself; she aims to absent herself while present. She doesn’t even really like to smile. Between the things she does write, there are chasms. As you read, those begin to be filled by a creeping sense of alarm, on your part, that gradually solidifies, becoming palpable. Two-thirds into translating the book, I felt suddenly rattled by its universe of small evils, very evil evils, chasing one another ominously across the page. They made me want to watch a Donald Duck cartoon one day, as though I were five and needed reassurance. But once back at the right distance again – out of the translator’s dirty mine – I could see all the little stones, their glint.

A line that aptly describes Jaeggy, borrowed from one of her stories, is: “Brevity, dissolution, cheer her.”

Read an extract from I Am the Brother of XX

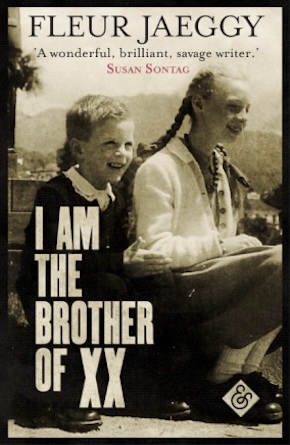

Fleur Jaeggy was born in Zurich and lives in Milan. The Times Literary Supplement named Jaeggy’s S.S. Proleterka (New Directions, 2003) a Best Book of the Year, and her Sweet Days of Discipline won the Premio Bagutta and the Premio Speciale Rapallo. She has translated the works of Marcel Schwob and Thomas de Quincey into Italian and written texts on them and on Keats. I Am the Brother of XX, translated by Gini Alhadeff, is published by New Directions in the US and And Other Stories in the UK.

Fleur Jaeggy was born in Zurich and lives in Milan. The Times Literary Supplement named Jaeggy’s S.S. Proleterka (New Directions, 2003) a Best Book of the Year, and her Sweet Days of Discipline won the Premio Bagutta and the Premio Speciale Rapallo. She has translated the works of Marcel Schwob and Thomas de Quincey into Italian and written texts on them and on Keats. I Am the Brother of XX, translated by Gini Alhadeff, is published by New Directions in the US and And Other Stories in the UK.

Read more

Gini Alhadeff grew up in Egypt, the Sudan, Italy and Japan, and studied fine art and photography in London and New York. Author of the memoir The Sun at Midday: Tales of a Mediterranean Family, the novel Diary of a Djinn, and a regular contributor to Italian Elle, Travel + Leisure and other magazines and journals, she is also the translator of Patrizia Cavalli’s My Poems Won’t Change the World.. She lives in New York City.