Writing about nothing

by Brett Marie

“Achingly beautiful.” New York Times

In a clip I never tire of watching, filmed on the Scandinavian leg of her 1976 tour, punk-rock legend Patti Smith takes perhaps the tamest song in the Velvet Underground’s repertoire and bawls it at us with a screech that is raw, ferocious, tortured. Her poet’s instincts turn Lou Reed’s bland line “lately you just make me mad” to the sublimely mournful “lately I just feel bad.” Her voice breaks intermittently like a saxophone player’s reed squeaking, then starts to tear as she holds that long note in the chorus: “Linger aaaaaaaaaaahhhhhhhhhhn, Pale blue eyes.”

Eyes closed, mouth agape, she veers close to sobbing the lyrics. After dozens of viewings, I still feel a touch of mist in the corners of my eyes by the last chorus. And at the final two repetitions of that refrain, without fail, I catch myself holding my breath in anticipation of what comes next.

“Louie Louie, oh, no…”

Her voice hardly changes, and at first she doesn’t do much more than slip the microphone out of its stand. But there’s no mistaking the sea change that takes place in the thump of a bass drum. For four minutes, Patti has dug us into a hole of melancholy. Now, with a swish of her hips she tosses us a rope and hoists us out into the light, and one of the dumbest songs in the history of rock ‘n’ roll (she alters the lyrics, but I defy you to decipher a word she says) becomes a triumphant anthem, one of rebellion against despair.

At her best, Patti Smith is a peerless performer, and one of the greatest artists of the past fifty years.

M Train is not Patti Smith at her best.

The new memoir would easily rival the anguish of her ‘Pale Blue Eyes’, if it ever faced directly the sorrows it shows in passing glances. It would soar higher than ‘Louie Louie’ if only she could deliver its life-affirming passages with conviction. Sadly, glances are the order of the day, and conviction is in short supply.

But hold it, you say. I’m being unfair. Can a clip of a singer at her youthful peak discredit a valuable work from a different era, in a different medium? Is it possible that I’m pigeonholing poor Patti? Do I refuse to perceive her as anything more than a great rock performer? Am I therefore choosing to scoff at a work of art merely because it falls outside of its creator’s normal sphere? Hardly. I can point to her first memoir Just Kids, the chronicle of her relationship with photographer Robert Mapplethorpe, as evidence that she’s capable of great literature. That book earned her the National Book Award for non-fiction – earned it, I say. Following such well-deserved success, it was only natural that Patti should take a stab at another Big Book. I jumped at the chance to get an advance copy.

Perhaps I was foolish, knowing what I know about her artistic temperament, to assume that what Just Kids did for Patti and Robert’s friendship, M Train would do for her relationship with MC5 guitarist Fred ‘Sonic’ Smith. For another writer, this would be a logical assumption: Fred was Patti’s other soulmate, both personally (as their fourteen-year marriage and two children attest), and creatively (the 1988 album Dream of Life was as much his album as it was hers). His untimely death was undoubtedly a monumental loss for her. An ordinary writer would follow that logic without a second thought. But this is no ordinary writer, no ordinary artist. I should have known.

Patti’s best music is sharp, to-the-point; the same goes for her writing. But from Page One, M Train is adrift.”

When the success of Just Kids made a follow-up inevitable, Patti must have chafed at the notion of a sequel, a rehash. Patti’s longtime guitar player Lenny Kaye captured her mindset best, talking about the early days of the Patti Smith Group: “The ultimate goal, as Patti would say, was that in every performance there should be something that had never happened before, that was a total surprise and totally unique to that performance. And we would spend a lot of time during the show looking for that moment, sometimes boring our audiences to death, or sometimes taking them to someplace that they’d never been before, too.” As in music, so too in writing: to do another straight memoir, to go back to that formula, ran against Patti’s deepest instincts.

Of course, Lenny’s explanation gives us a good insight into why Just Kids worked so well in the first place. Casual fans of Patti’s music knew her as the fiery punk-rock goddess with the soul of a poet. But few outside her cult fanbase were aware of her life-changing relationship with Robert Mapplethorpe. Telling the story of that romance-turned-friendship suited her artistic philosophy: here was something that Patti had never done in such vivid detail, an untold story that would surprise and delight many, one which would cast a new light on the impressive bodies of work that sprang from the story’s two protagonists, two artists who would grow into greatness but who were at the time of the narrative, literally, just kids.

Patti’s relationship with Robert wasn’t just something different for Patti to riff on, though. It also happened to contain all the elements of a perfect love story. It had a beginning, a middle and an end, following two young dreamers who grew and changed as human beings on their way to becoming great artists. Robert was a fascinating figure, a former altar-boy who discovered his homosexuality through street hustling inspired by the movie Midnight Cowboy, a driven artist without a defined medium until Patti, and fate, drew him to his calling of photography. Robert’s influence on Patti’s work – and work ethic – was powerful, and essential to her eventual success. Hear her admission, writing about the pre-fame era when they shared a loft down the street from the Chelsea Hotel: “Everything distracted me, but most of all myself. Robert would come over to my side of our loft and scold me. Without his arranging hand I lived in a state of heightened chaos. I set the typewriter on an orange crate. The floor was littered with pages of onionskin filled with half-written songs, meditations on the death of Mayakovsky, and ruminations about Bob Dylan… The wall was tacked with my heroes but my efforts seemed less than heroic. I sat on the floor and tried to write and chopped my hair instead. The things I thought would happen didn’t. Things I never anticipated unfolded.”

I think that it all comes down to focus. Patti’s best music is sharp, to-the-point; the same goes for her writing. Just Kids set out its goal (to portray the life and love of two artists) in a beautifully succinct foreword describing Patti’s quiet grief on the morning of Robert’s death in 1989. Throughout a narrative that spanned three decades, Just Kids kept its eye on that goal, never once losing touch with its themes of love, friendship and coming of age. But from Page One, M Train is adrift. Patti opens with a dream (always a bad sign, particularly in non-fiction), in which she engages in cryptic conversation with a nameless cowpoke (don’t ask). The key line is the first one the cowpoke utters: “It’s not so easy writing about nothing.”

What frustrates is that there is something essential here, it’s just buried so deep under a pile of creative chaff, that I can’t find the will to dig it out.”

From there, she sets out to prove that dubious thesis. We start at the Café ‘Ino, her regular haunt across from her Greenwich Village home, wherein Patti struggles to write, but gets distracted by her memories, her dreams, and the cafe’s staff and patrons. This sets the tone for the entire book: we will follow Patti as she meanders along a string of semi-interesting dreams and thought processes. We can just about see the tenuous threads that hold these thoughts together, but Patti seems too tired (she frequently stumbles between present and past tense within the same scene – sometimes the same paragraph) to tie them tightly enough for us to care about the piece as a whole. We trudge through one vignette after another; when one begins to drag on, we console ourselves that, at any moment, Patti will lose her train of thought and find something new and totally unrelated to talk about.

What did Just Kids teach us about Patti? That she was once young, idealistic and romanticised the life of the artist. That she could love someone with all her heart, that her love could transform itself into something stronger, more beautiful, when its romantic element was switched off.

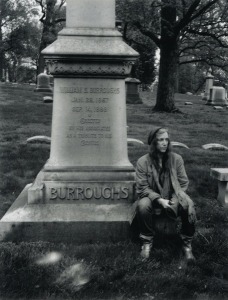

And what can we glean from M Train? That, damn, Patti loves coffee. And detective shows. (Page 237 of 253 – normally a section reserved for climactic revelations and bold statements – marks the beginning of a four-page ode to AMC’s remake of The Killing. Seriously, aside from the occasional poetic flourish, it reads as if she accidentally saved a Wikipedia entry in progress into the M Train folder of her laptop.) We know she had a husband, Fred somebody, and it’s clear she loved him, and misses him now that he’s gone. But every time we think she’s working herself up to talk directly about him at any real length, she’s off on a new tangent, about Murakami (she really dug The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle, folks), or her latest pilgrimage to the gravesite of one of her departed artistic idols. Surveying the book as a whole, contrasting Patti’s impassioned treatise on Detective Sarah Linden (“Linden has lost everything and now I am losing her… What do we do when [a TV show character] commingles with our own sense of self, then is transferred into a finite space within an on-demand portal?”) to her muted musing about the stormy night of her husband’s passing (“I could feel Fred closer than ever. His rage and sorrow for being torn away. The skylight was leaking badly. It was a time of tearing.”), it’s easy for us to misread which loss for her is devastating, and which one is just a drag.

Equally frustrating is her insistence on name-dropping her influences. Granted, this has always been her M.O. (in the cultural-references sweepstakes, only Woody Allen comes close). In Just Kids, this made sense, as artists such as Arthur Rimbaud, Bob Dylan and Allen Ginsberg served as inspiration, Patti’s springboard into the worlds of art and poetry. But the Patti Smith of M Train is already an artist in league with these legends, and has no need to refer to Jean Genet or Mikhail Bulgakov – or, for that matter, to the many TV crime dramas she devotes page after page to dissecting. After one overly-detailed allusion to one of her heroes, I was left practically shouting at the book, “Enough about their art! Get on with your own!”

What frustrates me most is that there are moments when Patti finds something interesting to say. The best stories in this book (which include a pilgrimage to a former French colonial prison and Patti’s purchase of a house on New York’s Rockaway Beach just before Hurricane Sandy wiped out the neighbourhood) could have stood alone as magazine pieces. And a few paragraphs before the end of the book, she regains her focus long enough to make a brilliant summation on life, death, love and art. There is something here, something new and unique to her oeuvre, something essential. It’s just buried, buried so deep under a pile of creative chaff, that I can’t find the will to dig it out.

Patti’s dogged determination to seek out unique artistic moments is laudable, even heroic. It requires her to be constantly on guard, to take risks and bear the consequences. Of course, in live music, there is no safety net, no way to get back the minutes or hours spent casting about for the unexpected and exciting. And so her audiences entered into a compact with her: they would consent to sit through the drudgery for the chance to catch the transcendent. But writing is a recorded medium. If something doesn’t work, it can be edited until it does, or thrown away altogether, without subjecting a single reader to it. Patti’s boldest statement in M Train is this promise: to keep on living, “refusing to surrender my pen.” Surely that should go for the red pen as well.

OK, enough negativity. If you’ll excuse me, I’m going to take another look at Stockholm, 1976. Here, enjoy it with me:

Maybe afterward I’ll take out my copy of Just Kids and reread a favourite chapter or two. I’m going to remind myself of what this great artist is capable of creating. There are still new artistic frontiers for Patti to explore; she’s probably already packing for one of them. And with M Train behind us, I still can’t wait to see where she goes next.

Brett Marie, also known as Mat Treiber, grew up in Montreal with an American father and a British mother and currently lives in Herefordshire. His short stories such as ‘Sex Education’, ‘Housewarming’, ‘The Squeegee Man’ and ‘Black Dress’ and other works have appeared in publications including The New Plains Review, The Impressment Gang and Bookanista, where he is a contributing editor. He recently completed his first novel The Upsetter Blog.

Facebook: Brett Marie

@brettmarie1979

M Train by Patti Smith is published by Bloomsbury in hardback and eBook. Read more.