One man’s trash

by Brett MariePick up your average celebrity memoir and you’re almost certain to find it dressed up in one of two ways. Some stars punctuate their life stories with matt black-and-white photos, neatly arranged over chapter headings or between sections. The more sensationalist among them choose the ‘16-Page Full-Colour Insert!’ (capitals and exclamation mark mandatory), helpfully collating all the glossy proof of their exploits in one place.

With his new take on the genre, Good Pop, Bad Pop, Jarvis Cocker has opted to shake up this formatting dichotomy. Perhaps ‘blow up’ is the better term; in fact, the Pulp mastermind has taken the format, crammed a lifetime’s accumulation of scraps and minutiae into it, and then let it burst forth in a disorganised heap which he proceeds, for over three hundred pages, to pick through. The result is a glorious mess – less a book than a Proustian punk-rock jumble sale – simultaneously a chronicle of one artist’s life, an exploration of the pop art and music that has always obsessed him, and an awestruck tribute to the ineffable miracle that is human creativity.

Good Pop, Bad Pop tumbles out from a simple premise: “There was a house I lived in for a while,” Cocker writes in his introduction. “I stored a lot of stuff in the loft of this house. When I say ‘stored a lot of stuff’ that’s really a polite way of saying ‘used it as a skip’.” After years of accumulation, “Circumstances have finally dictated that I now have no choice but to clear out this loft.”

Now, I don’t know about you, but if I were in Cocker’s place, I would google ‘junk removal’ rather than phone my publisher. Cocker’s brain works differently from mine, though. Here’s his reasoning:

“I have decided that, rather than simply take it all to the dump, I will look at every single item & then make an ‘informed’ decision as to whether to keep it or not.

“Why?

“Because I know that there’s something important in here somewhere. Some kind of life story, some kind of revelation – but we’re going to have to dig for it. I’m not using the royal ‘we’ – I’d like you to help me.”

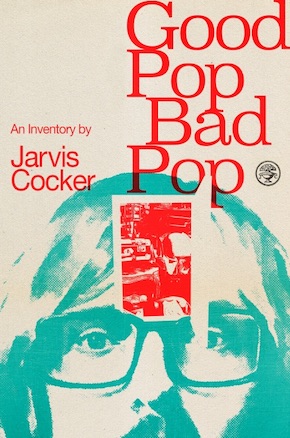

So Cocker isn’t just seeking aides-memoire for some run-of-the-mill autobiography. An anecdote from his youth, just a few pages later, hints again at this grander purpose: “One of the first songs I remember hearing on the radio is ‘Where Do You Go To My Lovely?’ by Peter Sarstedt which was a Number 1 hit in the UK for four weeks in 1969. The bit of the song that really got to me was a line in the chorus where he sang, ‘I can see inside your head.’ The idea that a stranger communicating with you via the radio might be able to do that both excited & terrified me.” Good Pop, Bad Pop’s mission, to perform a similar magic trick in print, is evidenced by its cover image: a door in Cocker’s forehead hangs open over those trademark glasses, evoking both the literal opening of his overstuffed loft and the parallel unlocking of his scattered brain.

Cocker’s raw wit is more than capable of holding a reader’s interest without the aid of props – but the random assortment of objects serves a number of purposes beyond gimmickry.”

Designer Julian House adds a delightful visual flourish to Cocker’s pages, laying the author’s various curios and doodads in front of us in lovingly haphazard fashion. Mostly absent are the scenes of studio knob-twiddling, onstage posturing and backstage hobnobbing that are the standard fare of music memoirs. Instead, here’s an ancient stick of gum (in vintage wrapper!) acting as a chapter heading. There’s a two-piece brass knick-knack spilling into the margins from between the lines. It’s hardly necessary – Cocker’s raw wit is more than capable of holding a reader’s interest without the aid of props – but the random assortment of objects serves a number of purposes beyond gimmickry. On a purely aesthetic level, the various scraps strewn between paragraphs jibe perfectly with a text littered with sentence fragments and ampersands. But these are more than simply clever decorations. They’re tools, useful both as storytelling prompts for Cocker and as the keys to a deeply immersive reader experience. Armed with these facsimiles in crisp focus and full colour, Cocker can stand us next to him under his low sloped ceiling, hold each item up for our inspection, and repeat in his Sheffield dialect the refrain of the recovering hoarder: Keep or Cob?

One astonishing piece at the top of Cocker’s Keep column is an exercise book from his schooldays. Stamped with the generic title ‘Science Book No. 4’ on the cover, it contains within its yellowing lined pages a schoolboy’s handwritten game plan for world domination by an as yet unformed group to be known as ‘Arabicus Pulp’. Cocker shows a fatherly pride for this fifteen-year-old version of himself, and considering the span of years between the inception captured in this seventies notebook and the eventual breakout of just-plain Pulp in the Britpop boom of the nineties, it is difficult to dismiss that young lad’s determination.

As any packrat who’s ever attempted a cull can attest, there’s no guarantee at the outset that this rummage will be a success. In much the same way that my own past clean-outs have quickly slowed to a crawl as more and more memory-laden objects caught my fancy, Cocker might easily get caught up with this or that old shirt or trinket and drag us down a rabbit-hole of nostalgia. And leaving aside the potential for distraction, the chaos inherent in his conceit – he is after all sifting through a pile of unrelated artifacts thrown together without thought over a period of years – could just as easily have scrambled any planned storyline into incoherence. But Cocker is an aesthete, and he freely admits to “a bit of stage-managing”. And though the depth of each of his specific fixations is often a shock, his deepest obsession of all is with the big picture. A childhood toy or scrap of paper might pull him, like a magnet, into a seemingly unrelated side story, but every tangent veers back toward the North Star of Cocker’s life’s journey and his main, unanswerable questions: What is Art? What is Life? What must we hold onto? and What can we throw away?

Over my years as a reviewer, I’ve amassed quite a collection of books. I used to move around a lot, but I’ve been in the same house for several years now, and the urgency for me to toss a less-than-adored novel or memoir for the sake of travelling light has receded. The volumes have started to pile up, and as my wife and I start murmuring anew about the possibility of moving on, I know that I’ll soon find myself playing my own epic game of Keep or Cob. I expect I’ll be downsizing, so the vast majority of items currently making my bookshelves sag are going to end up in the ‘Cob’ column. But there will be a few exceptions, and with its warmth, wit and infectious fascination with the underappreciated wonders of life and art, Good Pop, Bad Pop has already earned itself a solid ‘Keep’.

Jarvis Cocker is a musician and broadcaster from the north of England who now He divides his time between Paris, London and the Peak District. He formed the band Pulp in 1978 whilst at secondary school. They went on to become one of the most successful UK groups of the 1990s. Between 2009 and 2017 he presented the BBC 6 Music programme Jarvis Cocker’s Sunday Service as well as the ongoing, award-winning BBC Radio 4 documentary series Wireless Nights. He has honorary doctorates from both Sheffield Hallam University and Central Saint Martin’s School of Art (which he attended in 1988–91). His lyric collection Mother, Brother, Lover was published by Faber in 2011. Good Pop, Bad Pop, his first work of long-form prose, is published in hardback, eBook and audio download by Jonathan Cape/Vintage Digital.

Jarvis Cocker is a musician and broadcaster from the north of England who now He divides his time between Paris, London and the Peak District. He formed the band Pulp in 1978 whilst at secondary school. They went on to become one of the most successful UK groups of the 1990s. Between 2009 and 2017 he presented the BBC 6 Music programme Jarvis Cocker’s Sunday Service as well as the ongoing, award-winning BBC Radio 4 documentary series Wireless Nights. He has honorary doctorates from both Sheffield Hallam University and Central Saint Martin’s School of Art (which he attended in 1988–91). His lyric collection Mother, Brother, Lover was published by Faber in 2011. Good Pop, Bad Pop, his first work of long-form prose, is published in hardback, eBook and audio download by Jonathan Cape/Vintage Digital.

Read more

Instagram: jarvisbransoncocker

@JonathanCape

Author portrait © Tom Jamieson for The New York Times

Brett Marie, also known as Mat Treiber, grew up in Montreal with an American father and a British mother and currently lives in Herefordshire. His short stories and other writing have appeared in publications including The New Plains Review, The Impressment Gang, Pop Matters and Bookanista, where he is a contributing editor. His debut novel The Upsetter Blog is published by Owl Canyon Press.

Brett Marie, also known as Mat Treiber, grew up in Montreal with an American father and a British mother and currently lives in Herefordshire. His short stories and other writing have appeared in publications including The New Plains Review, The Impressment Gang, Pop Matters and Bookanista, where he is a contributing editor. His debut novel The Upsetter Blog is published by Owl Canyon Press.

Read more

@owlcanyonpress

Facebook: Brett Marie

@brettmarie1979

bookanista.com/author/brett-marie/

Author portrait © Roxanne Fontana