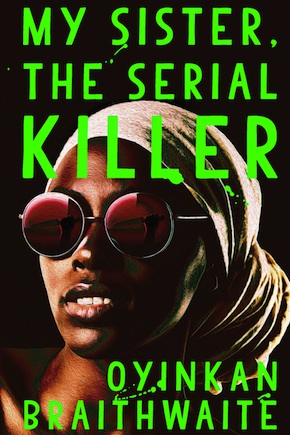

Oyinkan Braithwaite: Blood sisters

by Mark Reynolds

“A bombshell of a book… Sharp, explosive, hilarious.” The New York Times

If the title hasn’t already won you over, the opening lines hook you right in:

“Ayoola summons me with these words – Korede, I killed him.

I had hoped I would never hear those words again.”

Oyinkan Braithwaite’s debut novel My Sister, the Serial Killer is a pacy, macabre and very funny gallop through the agonies, apprehensions and collusions of two twenty-something sisters bottling up and battling duty, boredom and the demands of family. Korede is head nurse at a Lagos hospital, and a natural nurturer and mopper-up – which is handy since her younger sibling has the unfortunate habit of knocking off her many suitors. Korede’s practised routine of bleaching, scouring and disposing of dead bodies means there is never any trace of Ayoola’s crimes.

To ease her conscience, believing no harm can come of it, Korede confides in a comatose patient about Ayoola’s killing spree and her own cover-ups. When, with alarming alacrity, Ayoola starts dating a handsome doctor at the hospital called Tade, on whom her sister has an aching crush, there follows a dazzling quickstep of ethical dilemmas that stretch family ties to the limit. A book that started as a fun writing exercise to banish the demons of a weightier work she was struggling to pin down, it announces a supremely gifted young comic talent. But where will she go next?

MR: At what age did you decide you wanted to be a writer, and what were some of your earliest stories?

OB: I decided I wanted to be a writer at about age 9. I started off writing poetry – really terrible poetry – and one of my earliest stories I remember was about a woman, she was white and very beautiful with dark, long hair and she was wearing a white gown, and it was from the point of view of a forest. The trees and leaves are observing this beautiful young woman walking into a clearing, and they witness her stab herself. I was very descriptive about the red of the blood, and the fact she falls down dead. It was a very short story, that was pretty much it.

You’re the eldest of three sisters and a brother. Are you each very different or do you all have a lot in common?

We’re very different, especially the one who’s right after me, she and I are opposites, like now and again we’d question whether we came from the same set of parents. We get along – sometimes. Sometimes we just don’t talk to one another.

Is the novel based on an exaggerated version of your own family’s dynamics, or are you saying something about Nigerian society as a whole?

Both of those questions imply that I was doing something intentionally, but I wasn’t. I think maybe the closest thing to my family relationships is the two sisters. The father and mother are completely fictional, but looking back on it I do see some things that I took from my relationship with my sister, especially this idea of being the eldest, having to take responsibility for your younger siblings, having to look after them. So it’s like a really exaggerated telling of that sort of dynamic. But to be honest, the one after me, she’s actually more responsible. I’m a bit flighty, she’s the more domestic one, makes sure things are done properly. I’m a bit all over the place.

So you’re nothing like a neat and tidy as Korede?

Nooooo! In fact when my dad read the book, he was like, “Hmm, I wonder what kind of research you had to do to figure out how to clean up stuff!”

What is the worst you’ve had to clear up after your siblings? Or they after you…

The time I notice it the most is when my siblings get into trouble and maybe one of my parents is having a go at them and I think it isn’t justified and I get involved, and then I always end up being the one in trouble. Maybe because of the way I intervene. There have been a couple of times where I’ve thought it might be better to just let this thing run its course rather than get involved. But my siblings are generally quite straight and narrow, so to be honest I’ve probably got into the most trouble of all of us.

Is that because as the eldest you broke down all the barriers?

Yeah, I think that’s what it is. Part of the reason also why the last two don’t get in so much trouble is because my parents are more relaxed now. My brother is thirteen years younger than me, and he gets away with all sorts of things, they’re just not the same parents they were when I was growing up.

People have identified different themes in the book. I think the themes I stressed the most were ideas of family, of trauma and of beauty, and it’s interesting that people are talking about patriarchy and gender dynamics.”

It’s a very funny book that deals lightly with serious issues including gender roles, family violence and patriarchal society. What led you to focus on those issues?

Initially my main focus was on society’s interaction with beauty. That was my agenda if I had one, going into it, the other things just kind of happened, I think especially because of where I set it, just being true to where I was as a twenty-something in Lagos. Marriage prospects and the dynamic between male and female were very much at the forefront of your life. I’m 30 now, and I see the difference in the way people treat me now as opposed to when I was in my twenties, when they were panicking, like, “She’s unmarried, she’s a single, unmarried woman!”

I’m actually fascinated at how people have identified different themes in the book. I think the themes I stressed the most were maybe ideas of family, of trauma and of beauty, and it’s interesting that people are talking about patriarchy and gender dynamics, because even though they are there, I didn’t deal with them with any great purpose in mind.

But it’s fair to say there’s a sense that the men deserve what they get.

But it’s fair to say there’s a sense that the men deserve what they get.

Ha ha, yeah. Although actually I think I was kind to the men. I’ve definitely come across worse examples of the male gender than the men in this novel. I think people are imposing experiences of their own on the book. I’ve talked to two sets of women where they’ve said they really wanted Tade to die, and the second time I was having the conversation I said, “But do you guys really feel he deserves that?” Yes, he isn’t the best person ever, and he can be a bit of an ass, but I don’t think his actions warrant being killed. He didn’t assault anybody or anything, so I find it interesting that people want him to die.

He only falls for Ayoola’s obvious allure, without looking below the surface.

Yeah, his greatest fault is that he is shallow, and death’s not a fair punishment for shallowness.

In the end, it’s a powerful endorsement of sisterhood. Would you say it’s a feminist novel?

I wasn’t trying to write a feminist novel, but I think that most things I write will maybe come across as being feminist, because I’ve always had an interest in strong women, women having power and doing things deliberately even if those things happen to be bad. My favourite novel is Jane Eyre, and I guess people could argue differently but I perceive Jane to be a strong woman who has made deliberate decisions and chosen her path. So that’s where my interest lies, and perhaps it will always come across as being feminist.

I saw the YouTube film you made for Waterstones, where you mention Jane Eyre, and also Great Expectations and John Steptoe’s children’s book Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters. Can you explain how each of those was an influence on your novel?

It’s hard to say how they directly influenced it, but I’m seeing a lot of things in hindsight. I didn’t have them in my hands when I was starting this novel, but I can see similarities now. Jane Eyre was a plain woman, and it’s in the first person, and obviously the world wasn’t kind to her initially, so I can see similarities between her and Korede, because Korede’s also not someone who’s considered to be attractive, and it’s from her point of view. Then with Great Expectations, I had a really dark sensibility as a child, and I just loved Estella. Estella was bred to hurt men, that’s what Miss Havisham wanted her to do: for men to love her, and for her to be unlovable and for her to hurt them, and that’s very much like Ayoola. And Mufaro’s Beautiful Daughters is about two sisters, they’re both beautiful, and they’re fighting over a man. They leave their village and head to the city to meet the king, who’s supposed to choose a bride. But the mean one tries to get a head start so she can meet him first and he’ll fall in love with her, and on the way she gets waylaid by various people and she’s cruel to them, but when the kind daughter follows the same path she does nice things. Neither of them realises it’s a test, but it turns out the king had transformed himself into an old woman, a boy, whatever, he was all those characters they met along the road, and he already knows he doesn’t want the mean one. So there are two sisters fighting over a guy in the middle, and it’s that same idea that who you are on the inside is more important than who you are on the outside.

The short, action-filled chapters make for a really quick read. Did you write them in sequence, then go back and edit, or were you jumping back and forth between key scenes as you wrote?

I mostly wrote in sequence. But it wasn’t like one long document, I was writing it in parts so I wasn’t distracted by what came before. I treated each chapter as its own little package. And then editing I went back and created new chapters here and there in-between.

And how long was the writing process?

Initially it was a novella, so I wrote it in about a month because it wasn’t very long. And then once my agent saw it she asked me to do some work on it, and I went back and basically doubled the size, which took about another month. Then the editors came on and that took another couple of months.

I thought OK, forget about the noise and just write something for yourself, get it out of your system and then you can go back to the novel you want to write. It was just a fun little exercise.”

So to recap, the novella version was published as an eBook in Nigeria. What happened next? And when did your agents Aitken Alexander come onboard?

In 2016 I was shortlisted for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize, and Clare Alexander was a mentor on that prize and she saw my short story, which was a completely different story, and she liked it and asked if I had anything longer. I didn’t have anything I was comfortable sending so it was a year later when I sent her the novella.

I’d written it to exercise my writing muscles, because I had stopped writing for a little bit and I was starting to panic because I couldn’t write the novel I wanted to write. So I thought OK, forget about the noise and just write something fun, write something for yourself, get it out of your system and then you can go back to the novel. So that’s how this book came about, it was just a fun little exercise.

I put it on an eBook platform in Nigeria called Okada Books, for the equivalent of £1, and just waited to see if anybody would like it or read it. I have a friend who’s a writer and editor and she loved it, and she sent it to some people and they did some reviews, and I thought hang on a minute, this thing seems to be doing better than I thought it would. It seemed that whenever people read it, it was getting a very positive reaction. So I thought, you know what, you can’t expect to go back to Aitken Alexander forever, just send them this so they know you’re not dead. And things just kind of happened from there. Clare liked it and gave me some notes, I went back and worked on it, and they signed me on.

So it’s very different from anything else you’ve worked on. Is the other novel abandoned now, or are you going back to it?

That novel is abandoned. I abandon stuff a lot, it’s really bad, because I’m constantly distracting myself with other ideas which seem better. I’d written two novels before this, the second one was a fantasy, completely different, and it was about 100,000 words. So I’ve jumped about genre-wise quite a bit.

What kind of creative writing were you doing at Kingston?

Everything, we had to do everything until the third year when you focused a bit, so screenwriting, poetry, songwriting, short stories. We didn’t do novels, because obviously that requires a lot more time, but every other type of writing.

Which other contemporary Nigerian novels would you recommend?

The Secret Lives of Baba Segi’s Wives by Lola Shoneyin, I love that book. It’s also about patriarchy and relationships between women, it’s about a woman who marries into a polygamous home, the guy already has three wives, but she’s an educated woman, she has a degree, so at first you can’t understand why she’d marry into that sort of home. But the twist in the book is hilarious. I’d also recommend Stay With Me by Ayọ̀bámi Adébáyọ̀, but there are so many coming out all the time.

Your book has been optioned by Working Title. Has there been any discussion yet about whether they would film in Lagos?

Well, there hasn’t even been discussion yet about whether they will do it. It’s been optioned, but we haven’t gone in as far as where it would be set or anything like that, I’m just waiting to see if they will actually go ahead with it.

I would love to write a screenplay. As a writer I think my strength is dialogue, it’s something I really enjoy and that’s mostly what a screenplay is, so I would definitely like to try.”

How would you feel if they said let’s do it in Chicago, or wherever?

You know, one thing I realise now is the book is out of my hands. I no longer have control over how people receive it, I can’t even add a comma. The same thing with Working Title, I don’t really have control over it, and I have to be OK with whatever happens next. The impression they’ve given me so far is that they would keep the setting, the people, the culture. They’re really interested in its blackness as well, they really wanted to do justice to that. But I know that sometimes it can be complicated to film in Nigeria. I suspect with a lot of movies what they do is they film somewhere like South Africa and call it Nigeria and nobody will know the difference. But they might go to Nigeria and do everything there, they might do one or two scenes in Nigeria, or however they think they can manage it, but I think it’s more of a technicality thing than an intention.

Also it’s a very indoorsy novel, so they could probably manage to do the whole thing anywhere and call it Lagos and you may not be able to tell, because they’re in the hospital a lot, they’re in the home a lot. It’s only like the scene where Korede’s car is stopped by the LASTMA official and things like that where you’d really need to see Lagos.

Since you’ve dabbled in screenwriting, would you want to put yourself forward to adapt it?

It’s something I’d be interested in getting involved with at some point, but right now I’m trying to focus on writing a new novel. I would love to write a screenplay. As a writer I think my strength is dialogue, and maybe character too, but definitely dialogue is something I really enjoy and that’s mostly what a screenplay is, so I would definitely like to try.

What can you say about the next novel?

I have to give a disclaimer because I jump about so much there’s no guarantee I won’t leave this one, but I’m working on a dystopian novel, which is tough because description is not one of my strengths, and you have to be descriptive when you’re creating a hypothetical world.

Have you been reading a lot of other dystopian fiction to help establish the mood?

I watch a lot of dystopian movies. I bought The Power by Naomi Alderman, which won the Women’s Prize for Fiction, and I’ve recently been reading more dystopian fiction just to get a better idea of how people are doing it. But it’s a story set in Lagos still, so I’m also trying to understand more about how to go about creating a dystopian world in that backdrop. I might have to see who else has done that in Lagos, and how they pulled it off.

Are you using the first person again? Or do you find you need an objective narrator to build a bigger picture?

You know it’s funny, before this book as a writer I was not a massive fan of first person. I’m fine reading it, but I worried about how to distance myself from the voice. But now I’m finding it hard to go back to the third person, so it’s in the first person right now, but a multiple first person, that’s how I’m working it out right now, but we’ll see how it goes.

Oyinkan Braithwaite is a graduate of Creative Writing and Law from Kingston University. Following her degree, she worked as an assistant editor at Kachifo and has since been freelancing as a writer and editor. She has had short stories published in anthologies and has also self-published work. In 2014, she was shortlisted as a top ten spoken word artist in the Eko Poetry Slam, and in 2016 her story ‘The Driver’ was shortlisted for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize. My Sister, the Serial Killer is published in hardback and eBook by Atlantic Books.

Oyinkan Braithwaite is a graduate of Creative Writing and Law from Kingston University. Following her degree, she worked as an assistant editor at Kachifo and has since been freelancing as a writer and editor. She has had short stories published in anthologies and has also self-published work. In 2014, she was shortlisted as a top ten spoken word artist in the Eko Poetry Slam, and in 2016 her story ‘The Driver’ was shortlisted for the Commonwealth Short Story Prize. My Sister, the Serial Killer is published in hardback and eBook by Atlantic Books.

Read more

oyinkanbraithwaite.com

@OyinBraithwaite

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista