The Party of God

by Yamen Manai

“Manai delves into serious issues, but there’s also this humour, this passion, this humanity that buzzes around every page.” Writer’s Bone

The month of October, which would culminate with the nation’s first truly democratic elections, didn’t merely bring the forager bees’ beloved rosemary plants into bloom. The folds of its autumn coat were hiding strange birds that formed a new kind of convoy.

Contrary to the last caravan, primarily composed of young men and women waving the national flag, this one contained bearded men waving a black flag with a white pigeon in the center. Their appearance and way of talking stood out too. The previous canvassers had spoken the local dialect – an imperfect language stigmatized by history – and dressed like city folk, while these new canvassers were decked out in tunics, like the Bedouins of medieval Arabia, though, granted, very few things have evolved in Arabia since the Middle Ages. The nods to that bygone era didn’t stop with beards and clothing; these ornaments were enhanced by classical language, full of sacred words, echoing a rigorist rhetoric that the Nawis would soon discover.

These weren’t the only differences. Whereas the first convoy’s speaker system had broadcast bland, unconvincing patriotic chants, and their car trunks had been packed with pamphlets promising the moon, the loudspeakers of the second caravan emitted decibels of religious chants for the glory of God and the Last Prophet, and the beds of their pickup trucks were filled with crates of food, blankets, and clothes.

True, the country as a whole called itself a land of believers, some even going as far as to call it a land of saints, but nobody before these visitors had used that as a reason to save his fellow man.”

The bearded men parked next to the voting booth. Some began to unload the goods while others bellowed into megaphones, reminding their audience of God’s greatness, scattering Selim the shepherd’s sheep to the four corners of the valley, and attracting another flock composed of Nawis.

“God is great! God is great!”

The Nawis repeated after them, for how could they do otherwise. “God is great! God is great!”

“Come closer, my sisters, come closer, my brothers! Help yourselves! This is for you.”

“For us?”

“Yes! Help yourselves.”

Blankets, shoes, bags of clothes, bags of rice, boxes of canned food, cartons of soap, crates of meat, crates of vegetables, packets of cookies, and more. Never in their lives had the Nawis been the object of such solicitude; it was as if for one moment Heaven had opened its gates to them. The rush lasted at most half an hour, and then there was nothing left. By the end, on average, each Nawi had made three round trips between the distribution site and their shack, and had collected forty or so pounds of various foodstuffs.

When the villagers returned to the square to thank their bearded benefactors, the latter denied being the source of any charity whatsoever. “My brothers, we are servants of God. We are only doing our duty. It is our duty to come to your aid.”

The Nawis were confused. True, the country as a whole called itself a land of believers, some even going as far as to call it a land of saints, but nobody before these visitors had used that as a reason to save his fellow man.

The most heavily bearded member of the assembly, who appeared to be the leader, continued the speech. His head of hair and belly were equally impressive. What’s more, the green mark above his eyes left little doubt about the incalculable number of hours he spent in prayer, forehead against the ground. His wall-eyed gaze, one motionless orb fixed on the horizon, lent him a mystical air, and his melodious voice resonated with emotions, from shrillest to deepest. After having exalted the All-Powerful countless times, and praising His Prophet, the Last Prophet, he said:

“My brothers and sisters, it is I who must thank you from the bottom of my heart. Because of you, today, my day is beautiful, and I have gained a plot in Heaven. What better could befall a man than to prepare his eternal home by following the path of the Eternal in his earthly life? That is the reason I am here among you, with my hand stretched out. God is my choice. His word, my law. So, when the time comes, do as I did, choose God! When the time comes to vote, vote for the Party of God!”

Then the tone of his voice became more instructive and authoritative as he unfolded a paper ballot with multiple boxes next to multiple emblems.

“Once you’re in the voting booth, you check here, check the pigeon,” he explained.

The pigeon was the emblem of the Party of God.

—

The week between this visit and the elections was pleasant in the village. At night, the Nawis slept with their bellies full, beneath warm blankets, and when they woke, they dressed in their new tunics. The day of, those who were old enough to vote showed up early and checked the pigeon. All the Nawis. Well, with one exception.

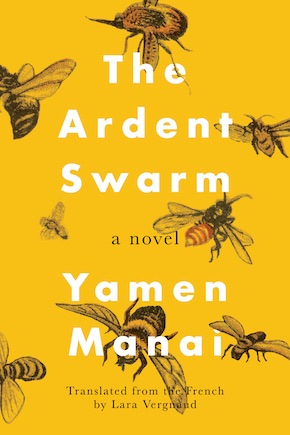

from The Ardent Swarm (Amazon Crossing)

Yamen Manai was born in 1980 in Tunis and currently lives in Paris. A writer and an engineer, in his prose Manai explores the intersections of past and present, tradition and technology. In The Ardent Swarm (originally published as L’Amas ardent), his first book to be translated into English, he celebrates Tunisia’s rich oral culture, a tradition abounding in wry, often fatalistic humour, in a modern-day parable of democracy and fundamentalism from the viewpoint of a hermetic beekeeper. He has published three novels with the Tunisia-based Elyzad Editions, ensuring his books are accessible to Tunisian readers: La marche de l’incertitude (2010), awarded Tunisia’s prestigious Prix Comar d’Or; La sérénade d’Ibrahim Santos (2011); and L’Amas ardent (2017), which earned both the Prix Comar d’Or and the Prix des Cinq Continents, a literary prize recognising exceptional Francophone literature. The Ardent Swarm, translated by Lara Vergnaud, is published by Amazon Crossing, Kindle and Audible.

Yamen Manai was born in 1980 in Tunis and currently lives in Paris. A writer and an engineer, in his prose Manai explores the intersections of past and present, tradition and technology. In The Ardent Swarm (originally published as L’Amas ardent), his first book to be translated into English, he celebrates Tunisia’s rich oral culture, a tradition abounding in wry, often fatalistic humour, in a modern-day parable of democracy and fundamentalism from the viewpoint of a hermetic beekeeper. He has published three novels with the Tunisia-based Elyzad Editions, ensuring his books are accessible to Tunisian readers: La marche de l’incertitude (2010), awarded Tunisia’s prestigious Prix Comar d’Or; La sérénade d’Ibrahim Santos (2011); and L’Amas ardent (2017), which earned both the Prix Comar d’Or and the Prix des Cinq Continents, a literary prize recognising exceptional Francophone literature. The Ardent Swarm, translated by Lara Vergnaud, is published by Amazon Crossing, Kindle and Audible.

Read more

amazonpublishing

@AmazonPub

Author portrait © Delphine Manai

Lara Vergnaud is a literary translator from the French. Her translations include Ahmed Bouanani’s The Hospital (New Directions, 2018) and Zahia Rahmani’s France, Story of a Childhood (Yale University Press, 2016), as well as works by Mohamed Leftah, Joy Sorman, and Scholastique Mukasonga, among others. Lara is the recipient of two PEN/Heim Translation Grants and a French Voices Grand Prize and has been nominated for the National Translation Award.

Lara Vergnaud is a literary translator from the French. Her translations include Ahmed Bouanani’s The Hospital (New Directions, 2018) and Zahia Rahmani’s France, Story of a Childhood (Yale University Press, 2016), as well as works by Mohamed Leftah, Joy Sorman, and Scholastique Mukasonga, among others. Lara is the recipient of two PEN/Heim Translation Grants and a French Voices Grand Prize and has been nominated for the National Translation Award.

@laravergnaud

Photo © Pascal Michel