Louise Kennedy: Marks on the ground

by Mark Reynolds

“A masterclass by a major talent.” The Irish Times

Shortlisted for the Sunday Times Audible Short Story Award in both 2019 and 2020, and the recipient of many earlier awards, Louise Kennedy has become a leading light in Irish storytelling. Having worked mostly as a chef for thirty years, she began writing at the age of 47 in 2014, and has since completed an MA and PhD in Creative Writing from Queen’s University Belfast.

The title story in her forceful, disconcerting and intensely funny debut story collection The End of the World is a Cul de Sac is about an abandoned housing development – and an abandoned wife – and reflects the economic boom and bust across all of Ireland in recent decades. There’s a granite dome depicting the name of the estate in a Celtic font deposited on top of a fairy fort, and we’re introduced to the derelict homes on the morning a donkey has broken into the show house and shat all over the floors and walls. Sarah’s a wreck, her husband Davy’s done a runner to escape his debts – and his guilt at having ruined Sarah’s sister and brother-in-law by persuading them to buy one of the houses on the estate.

“I live in the northwest of Ireland,” says Louise, “where there are really obvious marks on the landscape going back thousands of years. I live in Sligo town, and within about a three-minute walk of my house there’s a fairy fort in the grounds of a telecom provider’s campus. From one of the windows upstairs I can see a man-made cairn that’s about four thousand years old, where Queen Maeve is supposed to be buried. So all of those old marks are on the landscape, but then there are also the newer marks, and some of those are the lovely mock-Gothic buildings in Sligo town like the courthouse, but then there are the ghost estates. These were houses that couldn’t really be sold and probably shouldn’t have been built in the places they were built, where there weren’t bus routes, there weren’t schools, or there was no population, and sometimes these houses were very high-spec. The other thing here that’s kind of noticeable in the last thirty years is that there isn’t really a uniform architecture. So you do occasionally get these mad-looking James Bond-type houses beside like a mock Queen Anne mansion or something, and then down from that a bit would be a bungalow from the 60s.

“The bank guarantee thing is when all the shit came to a head, but there’d been problems for about three years, you know, the housing market had collapsed, and these estates had been abandoned. There are still rusty cranes hanging over rivers and salmon leaps – I don’t know if anybody even knows who owns the cranes at this stage. So I guess all of that was on my mind, all the ugly marks on the landscape, and then some of the older and more beautiful marks, and they’re all made by human activity. It’d be difficult to live here and not be aware of what we’ve done to the place. There’s another story in the collection called ‘Wolf Point’, which is based on a place I walk where there are all these ludicrous follies that were built by the Anglo-Irish landowners, that are bigger than the tiny little bothies that whole families lived in, so I guess all of that is in there as well.”

All of that was on my mind, all the ugly marks on the landscape, and then some of the older and more beautiful marks made by human activity. It’d be difficult to live here and not be aware of what we’ve done to the place.”

‘In Silhouette’, which was Louise’s first story to be shortlisted for the Sunday Times prize, slips between The Troubles in the 1970s and 80s and the present, and between Northern Ireland and London. The period detail will chime with anyone who lived through the 70s: trampy hot pants and yellow flares, Purdey hairstyles, Showaddywaddy on Seaside Special, and “jewel-coloured drinks laced with cordial. Gin and orange. Pernod and Blackcurrant. Vodka and lime.” The protagonist’s brother was caught up in terrorist activities and killed, but there is nostalgia for the old place and a lost pub that seems to recall a place her family ran back in the day.

“Yeah, so my family did have a pub in the 70s. It was blown up twice – not very drastically, nobody was killed or anything, which in those days was like a fabulous bonus, but there was a bomb, and then there was another bomb, and I guess at that point my family got the message and sold the pub, and that’s how we eventually ended up living in the South. That was in ’75, some of my family had to leave in ’75 and we eventually left in ’79. I’m not going to say I was brought up in a pub, but certainly my father’s family had a pub and I was probably in there sitting at the counter eating crisps and trying to get them to give me Babycham to drink because I was convinced that with the Bambi on it, it had to be non-alcoholic, but they weren’t going for it.

“It’s not autobiographical because I do not have a brother who was in the IRA or tried to go on hunger strike, or involved in anything like that. I do not know what happened to any of the disappeared in The Troubles, I have to clarify all of that. But I guess the details that I used would be based on things that I know very well. I know what a pub in Northern Ireland looked like in the 70s, and I know what the borderlands look like. I live in the northwest, and for the last five years I’ve been travelling regularly to Belfast in the northeast, through the borderlands and across South Ulster, so I guess a lot of that was in my mind over the last few years as I was writing. I think most people’s experience of The Troubles was, I don’t want to say second-hand, but I think there was a general trauma, we were all nervous wrecks. My friend who lived across the street, her father was a Catholic policeman and he used to check under his car for bombs in the morning, and then later my father worked in a place where he was the only Catholic in a large workforce and he would’ve checked under his car for bombs. In some ways it was a very normal childhood, you know, we lived in a bungalow and played on a street, there weren’t troops on the street or anything. But also, when I compare it to the way my children are being brought up, it was actually nuts.”

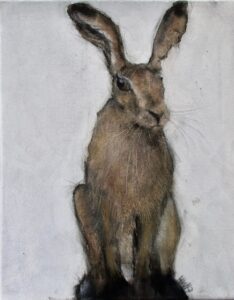

August Hare by Heidi Wickham, 2017. heidiwickham.com

In ‘Hunter-gatherers’, Siobhán and Sid are renting the gate lodge of a country estate, where they forage off the land and he works as a beater on pheasant shoots, while his gruff friend Peadar is gamekeeper. Siobhán agonises over a bird that is winged on the shoot, but Sid shrugs it off. She is later horrified when Peadar urges his girlfriend’s young daughter Rachael to kill a hare that has been visiting Sid and Siobhán’s garden. The reader is left with the image of a hare in a book of folk tales collected by Yeats: “She could hardly believe the illustration: the close thicket of trees, the candyfloss tail and meaty hind legs clearing a hedge, ears in a V-sign. She read the story three times. It was about a man who is led astray on a hunt by a mysterious hare and is never seen again.”

“Yeats and Lady Gregory – this is part of the Celtic revival in the late 1900s – they travelled around and collected folklore from local people. Augusta Gregory would’ve done it in the part of Galway she lived in, and Yeats did it in Sligo, where his mother’s family were from, and they collected all these stories, some of which are actually quite nuts but very cute as well. I worked in a library – I shouldn’t be saying this, I probably should’ve been like dusting or something, or shelving things and cataloguing, but actually I was hiding at the back reading folklore collected by Yeats. The way he writes them, he doesn’t really quite write them up as stories, a lot of it was about the gathering of the stories as much as the narratives themselves. But I couldn’t believe my luck when I was writing my story and I found that story about the hare, it was kind of amazing.”

Louise’s second story that was selected for the Sunday Times prize – and also for the Writing.ie Story of the Year – is ‘Sparing the Heather’. In it, Mairead is having an increasingly reckless affair with English gamekeeper Hugh, from whom she collects rent on behalf of husband Brendan. As the village gathers for the grouse hunt, and the Guards search the moors for missing human remains, Mairead is at breaking point because she can no longer keep a dark secret of Brendan’s to herself. The tense atmosphere is exacerbated by wild nature and punishing weather, and Mairaed is a perfect example of what Caoilinn Hughes has described as Louise’s “army of complex, contradictory, haywire women.” The stories are filled with depictions of trapped and abandoned women, but in point of fact the men in the stories are no less trapped or lost.

I had it in my head that women screw up as much as men do, and I didn’t want to have this army of female victims, because I don’t really think that’s how life works all the time.”

“Yeah, that’s kind of interesting, because all of these stories, the ones that you’ve talked about, are narrated by women, but I was surprised when I went back and counted that four out of the fifteen stories are written from the point of view of male protagonists. I had it in my head that women screw up as much as men do, and I didn’t want to have this army of female victims, because I don’t really think that’s how life works all the time. I don’t know if you noticed but ‘In Silhouette’ and ‘Sparing the Heather’ are, I guess they’re sisters, maybe mother and daughter? So I started trying to write a story that was ‘Sparing the Heather’ and it was really difficult. I couldn’t make my mind up whose story it was, so I changed it. I had it written from the point of view of a few different characters, but I knew there was going to be a body, and there was going to be a grouse moor, and there was going to be an Englishman, but I didn’t know what else to do with it.

“I probably wrote about 45,000 words of stops and starts, trying to figure out what the hell that story was about, and then I wrote like a little vignette, which was a flashback in the second person, and I felt that I’d hit on something, so I kept going, and that ended up being ‘In Silhouette’. So when I finished that, I went back and then I thought OK, so I’ve written this story and I know ‘Sparing the Heather’ is not about that, but I just had this idea that for a lot of people their experience of The Troubles would’ve been sometimes that they knew things that they’d rather not know. Because it was all very clandestine, very often there was a lot of silence around things that people knew, and that was kind of as far as their involvement went, because realistically it was not that many people that were actively involved. Enough to wreck the place, but not that many. So I guess I figured out that one of the women had to clean up after her brother murdered the man, and then that the other woman knew where his body was. Because one of the biggest legacy issues of The Troubles is about the Disappeared, which is a really inadequate word, I think. A lot of people went missing, and at least three bodies are yet to be found.”

Most of the stories are about ordinary lives in the borderlands. But ‘Beyond Carthage’ sees two middle-aged female friends on a haphazard adventure outside their comfort zone involving heavy drinking and grubby sex in out-of-season Tunisia.

“OK, so I was on a holiday from hell. I have to qualify here that I didn’t have a knee-trembler with a DJ in a hotel corridor. But I was on a horrendous package holiday to Tunisia in the ’90s with a couple of friends, so I guess that was the setting. I’d been reading about Dido, and I wanted to kind of muck around with the Carthage idea. The Tunisians were very proud of how the place was quite recently developed and it was quite modern and everything, and it probably was quite nice for them to live somewhere that has like plumbing and electricity and everything, but you know when people go on holiday they’re looking for this sort of gorgeous, idealised version of a place, so we were bitterly disappointed that it was too clean and tidy and everything was concrete. There weren’t really that many places to visit, except the ruins of Carthage and Sidi Bou Said, a bit further out.”

In her thirty-year career as a chef, Louise spent four years working in Beirut.

“In my early twenties I suffered from very irrational, really crippling anxiety, so part of the reason I cooked was because I couldn’t have gone to an interview or anything, I just wouldn’t have been able to speak. So once I learned to cook, it meant that I just had to turn up with an apron and a chef’s hat and a knife and they’d let me work away. My brother-in-law went to work in Beirut, and my sister and her two very small children went along as well, and I went to stay with them, supposedly for three or four weeks, but I ended up staying for a few years. I loved it, it was fantastic. It’s quite heartbreaking the state of the place now, it’s really quite wrecked, but at that time it was a very optimistic sort of place. It was about four years after the Civil War ended, and a lot of Lebanese had come back from all over the world to set up businesses, and there were people from everywhere there working on the rebuilding, and it was just a really hopeful, positive place. For all the wreckage and stuff, I thought it was really quite beautiful as well, so it was a great place to live for a while.”

When I started to write at 47, I wasn’t one of those people who’d been scribbling away privately. I literally hadn’t written anything, I’d been running around kitchens, shouting at people to get dinners out.”

So what were the other highlights – and lowlights – of being a chef?

“For the highlights, I have to say, on a Saturday night – this was me in my twenties and early thirties – before you get to the point where you’re like, ‘Oh Christ, not this again,’ and ‘Why am I working another weekend?’ there is a point when you start to see a restaurant fill up, and you get that adrenaline rush when you think, ‘I just have to fucking feed this lot,’ it’s kind of amazing. And I think as well the satisfaction that you get, you know instantly if a plate of food is right. You don’t have to wait around for somebody to analyse it, you know straightaway if it looks the part, and I think that can be really, really gratifying. And then the downside is horrific hours, constant stress, just living on coffee and cigarettes – a lot of people only smoke because it’s the only hope in hell you have of getting a break.

“When I started to write at 47, I wasn’t one of those people who’d been scribbling away privately, writing all these poems really intensely for years on the sly. I literally hadn’t written anything, I’d been running around kitchens, shouting at people to get dinners out.”

There’s been a resurgence of interest in Irish writers among UK publishers in recent years. I ask Louise what she would put that down to, and which contemporary Irish writers she particularly admires.

“I think there’s a tremendous energy in the country at the moment, and I definitely think journals like The Stinging Fly, Banshee, The Tangerine are driving some of that. They get huge submissions from all over the world, and there are tremendous efforts to try and keep the quality up.

“I think Sally Rooney is amazing, I really do, there was a short story of hers called ‘Mr Salary’ that was shortlisted for the Sunday Times award in 2017, and I was reading it on my phone while I was plating dinner for my children, and I literally burst into tears at one point. There’s tremendous control and emotional heft in her writing. I also really love Caoilinn Hughes, Elaine Feeney, Sinéad Gleeson, John Patrick McHugh, Anne Enright, and I really, really, really, really love Edna O’Brien.”

Where lockdown has knocked many of our plans for six, after an uncertain start it could hardly have gone more productively for Louise.

“I found the first month and this past month a bit freaky, but apart from that I had so much to do. I wasn’t getting a lot done in the beginning, I probably had a month of freaking out going, ‘What the hell is this?’ I think we were all a bit like that, looking at the footage from Italy and Spain, and we all thought, ‘So this is coming,’ and it just looked so awful. So I spent that month trying to do deep breathing exercises and reading novels and making banana bread, and then after that I just thought, look, there’s plenty to be doing, so I brought my novel on probably by about another two or three drafts, and I finished the PhD that had been hanging over my head for a while, I wrote a couple of stories, did copyedits on the short story collection. I mean, there was nowhere to go and nothing else to do. The novel is with my editor, and I’m sure she’s going to come back with lots of suggestions for me to fix it up. It’s set in the North of Ireland in 1975, and it’s about a relationship that probably doesn’t have a lot of chance of working…”

So finally, after putting all that work in, what is Louise most looking forward to after lockdown?

“Having a pint of Guinness in a pub. With other people. Yeah, that’s what I’m looking forward to most.”

Louise Kennedy grew up in Hollywood, County Down, and from the age of 12 in Kildare and Dublin. Her short stories have appeared in journals including The Stinging Fly, The Tangerine, Banshee, Wasafiri and Ambit, and she has written for the Guardian, The Irish Times, BBC Radio 4 and RTE Radio 1. She lives in Sligo. The End of the World is a Cul de Sac is published by Bloomsbury in hardback and eBook.

Louise Kennedy grew up in Hollywood, County Down, and from the age of 12 in Kildare and Dublin. Her short stories have appeared in journals including The Stinging Fly, The Tangerine, Banshee, Wasafiri and Ambit, and she has written for the Guardian, The Irish Times, BBC Radio 4 and RTE Radio 1. She lives in Sligo. The End of the World is a Cul de Sac is published by Bloomsbury in hardback and eBook.

Read more

louise.kennedyy

@KennedyLoulou

@BloomsburyBooks

Mark Reynolds is a freelance editor and writer, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@bookanista

wearebookanista

bookanista.com/author/mark