Patrick Ryan: Connecting lives

by Farhana Gani

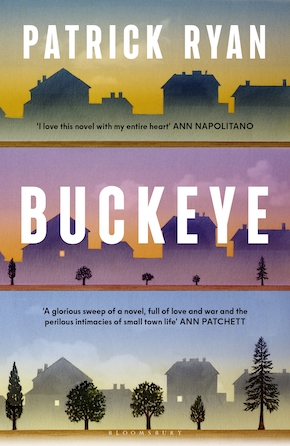

PATRICK RYAN’S CRITICALLY ACCLAIMED short story collection The Dream Life of Astronauts (2017) marked him out as a writer to watch. His stories brim with rounded often-unforgettable characters living quietly, with yearning, humanity and acceptance. He is a master of dialogue, the unsentimental and the subtle. So when his debut novel Buckeye arrived, I approached it with a mix of anticipation (his short fiction is so beautifully crafted) and hesitation (could he sustain that same brilliance across the breadth of a novel?). I settled in for the ride.

And what a time-travelling ride it turned out to be. Set largely in Bonhomie, Ohio, between the 1920s and 1970s, Buckeye revolves around two couples in smalltown America. There are wars, marriages, births, deaths, conflicts, betrayals and an over-arching desire to live well and true, considerately and purposefully. It reads like a literary soap, yet without any of the schmaltz or melodrama that often weighs sweeping family sagas down.

Cal Jenkins is married to Becky and Margaret Salt is married to Felix, and these are the characters we spend most of our time with. Their lives, chronicled from childhood through middle-age, unfold in a clever non-linear fashion. Cal, prevented from joining the war effort by a birth defect, remains in Bonhomie. Felix volunteers for naval service. The day the Second World War is declared over, their lives become intertwined forever, and the consequences of war ripple through their marriages, their friendships, and eventually their children’s lives, shaping events that are by turns explosive, tender, bittersweet, tragic and redemptive.

Ryan’s skill in letting a story wrap itself around you, and reveal itself layer by layer, is cleverly at play here. Buckeye swings back and forth in time, and from character to character. By moving seamlessly between time periods and perspectives, he builds a vivid portrait not only by bringing individuals to life, but by building their community. It’s a marvellous and satisfying device which, in its entirety, reads like a carefully mapped social history of a Midwestern town, leaving you steeped in their world.

It’s a strong contender for my best novel of 2025. I caught up with Patrick Ryan to look deeper into how he developed the fictional town of Bonhomie and breathed life into the people who inhabit it.

Farhana: Congratulations on your beautiful, bittersweet novel. Love, death, birth, marriage and the impact of war are central to the plot. Can you give us your elevator pitch?

Patrick: Thank you! Here’s the elevator pitch (for a tall building): Buckeye is set in a small town in Ohio, opens at the moment of the Allied victory in Europe during WWII, spans forty years, and is about two families whose lives become intertwined and compounded by one bad decision and one big mistake that will redefine both them and the next generation.

Buckeye reads like a significant chapter in the story of white, upwardly mobile American society from the 1920s to the 1970s. What were your influences, and can you share what first triggered the idea for you?

My influences came, in part, from a lot of my early reading as a teenager – and I read widely, without much guidance: literary fiction and popular fiction and genre fiction and trashy novels. I learned a lot about what fiction can do that way. Later, I was influenced by Pat Barker’s Regeneration and Life Class trilogies, by all of Elizabeth Strout’s writing, and by Nicholson Baker’s fascinating non-fiction book Human Smoke. I am forever inspired by what I think is one of the best books about the United States ever written, The Grapes of Wrath. Hugely moving books that don’t feel like books so much as like lives. Like life.

The first spark for this novel was my finding out that my paternal grandmother – a pious and difficult person – had maintained an affair with someone in her small town for decades. I had no interest in writing about her, but that situation intrigued me: small community, huge deceit, plus the time period – the 1940s, 50s, 60s – and all the complications that might arise.

The characters matter most to me. As a writer, I work hard to make them convincing to me, so that they have a chance of convincing the reader.”

When did you start working on Buckeye? Any insights you can share on your writing process?

I started working on Buckeye in the summer of 2016. My process is that I write slowly and revise constantly. It’s not a great way to work, because the forward progress can be almost undetectable for long periods of time. I also print often, take a red pen to the pages, and mark up ruthlessly. I wrote three drafts of the novel over a six-year period. Then, after it was acquired by Random House, I worked for an additional two years on another three drafts with my editor. She pulled no punches, and I’m grateful.

What forms of research did you undertake?

I read novels and historical writing and memoirs. I read quite a few books about the US during the First and Second World War. I read a lot of articles I found online, of course. And I spoke to several people with knowledge about various aspects of the subject matter, including interviewing a nonagenarian veteran.

Your novel is set in a small town in the American Midwest over several decades. Tell us about how you developed your storylines, locations and structure.

I chose the location because, having grown up in Florida, and having grandparents from Ohio, I grew up very intrigued by the Midwest. Also, I lived in Ohio for two years while I attended graduate school, and I had a flavor for the atmosphere there and knew it suited what I wanted to write about.

Structurally, it was my intention to be as chronological as possible, but once I had the basic story worked out, I knew I couldn’t tell it that way. The idea was always to have the novel open with two strangers meeting. That meant I then needed to back up and tell how each of them got there. The book takes some risks in terms of structure, I think, because it shows the reader an important moment in these characters’ lives, then backs up and works its way toward that moment twice, from two different angles. Then it proceeds to span four decades.

The characters matter most to me. As a writer, I work hard to make them convincing to me, so that they have a chance of convincing the reader, and once I get a solid grasp on them and have figured out their arcs and where they’re each going to land emotionally, I feel a responsibility to see them through. Also, to explore them thoroughly. It doesn’t all find its way to the page, but I have to do the exploration for what’s on the page to work.

In Cal, Becky, Felix, Margaret, Lydia, Everett, Skip and Tom, you’ve created an ensemble cast of engaging multi-generational characters who each come to the fore at different stages. Was this always your intention?

Yes. But I didn’t know how their storylines were going to play off one another, in some instances, until I got deep in. For example, without giving anything away, I didn’t know the paths the boys were going to take – the next generation – until I’d spent a few years getting to know them.

Felix is an all-American hero with a secret he can’t share. It’s a bittersweet life and for many he will be the heart of the novel. Did you base him on anyone specific?

He’s an amalgamation of some earnest men I’ve known who were married when they probably shouldn’t have been and were trying to make the best of their situation – not just for themselves but for their families. From afar, I’ve imagined the kinds of conversations they needed to have with themselves to keep going and maintain a level demeanor, and the way they might feel the need to constantly recast themselves as something they’re not.

I had to confront the common misconception that racism in the United States is contained within the South. It was – and is – worse in the south, but it’s also bad everywhere in the US and always has been.”

The Thomas Aquinas quote, “The things that we love tell us what we are”, resonates throughout the novel and has a profound impact on Felix. Tell us about your reasons for referencing Aquinas, and choosing that particular sentiment.

I like that quote because it steers us toward paying attention to what we love as a means of self-evaluation. Isn’t that the best kind of inward looking? Look inward by noticing how you look outward. I thought it rang true, too, that a character like Augie would hear it and latch onto it – and that it would resonate with Felix, who, over the course of the novel, is coming to terms with his love and how it defines him.

Becky’s story is eye-widening. You’ve created a believable character who can talk to spirits in the afterlife without her coming across as woo-woo. How did you pull this off?

I’m so relieved to hear it! I wanted her to have the ability – really have it – and not explain how or why she has it, because she herself doesn’t know. And I became very interested in how all the people around her react to this power. The ones who don’t believe in it and need it are, of course, the ones who feel threatened by it.

For a long time, I didn’t know how large a part her spiriting was going to play in the book. I was worried about the woo-woo factor and wasn’t sure it could be avoided. But one of my favorite characters in the novel is Mrs Dodson, and she’s one of only three who appear on both sides of the afterlife. Once I wrote about her demeanor on the Other Side, I felt thoroughly committed to seeing where this led.

Your novel doesn’t shy away from American prejudice and there are hints of the black American experience, via Vincent, and attitudes to non-whites, via Becky’s father Roman. How did you go about achieving the right balance?

First, I had to confront the common misconception that racism in the United States is contained within the South. It was – and is – worse in the south, but it’s also bad everywhere in the US and always has been. The second thing I wanted to explore was the phenomenon that people in a position of comfort sometimes can’t conceive of themselves as racist because they aren’t out doing racist things in public.

The younger generation, Tom and Skip, head in different directions with consequences. Education feels like a significant factor, particularly for Tom’s anti-war position. What would he make of America today?

He would be horrified, sickened, and angry.

I’m particularly drawn to how much acceptance there is in your novel. The characters are living, breathing and passionate – yet they also quietly get on with their lives in the aftermath of loss and betrayal without soap-opera dramatics on the page. Any tips you can share on character development?

Thank you. It’s so important to me that the reader not only believes but understands and cares about the characters. The reader doesn’t have to like them, but the reader should feel invested, and to feel invested they have to care. I’m not driven by or very interested in plot. I sort of figure out plot as I go and let a lot of it be determined by the emotional throughlines of the characters. It almost feels like a collaboration between me and the people in the novel after a certain point, if it’s going well.

My advice is to make learning your characters your top priority, because writing fiction isn’t just figuring out who the characters are and what the story is and then clothes-pinning the characters to the story; a big part of it is getting into a situation with characters who matter to you, and then paying attention to what they want and don’t want to do next, based upon who they are.

I’d be surprised if Buckeye isn’t adapted for TV. Any developments on this front?

No. I suppose “not yet” is a more optimistic answer.

What’s keeping you busy at the moment?

I’m taking notes on some new characters and situations that might come together into a novel, and I’m figuring out how to talk about Buckeye. It’s amazing to me that I can spend eight years working on something, and when it’s finished I find it challenging to explain. But I’m learning – with your help! Thank you for these excellent questions.

—

Patrick Ryan is the author of short story collections The Dream Life of Astronauts and Send Me. His writing has appeared in The Best American Short Stories, the anthology Tales of Two Cities and elsewhere. A former associate editor of Granta and current editor-in-chief of One Story, he lives in New York City. Buckeye is published by Bloomsbury.

Read more

patrickryanbooks.com

@patrickryannyc

@bloomsburypublishing

@bloomsburybooksuk.bsky.social

Author photo by Fred Blair

Farhana Gani is a freelance copywriter and book scout for film and TV, and a founding editor of Bookanista.

@wearebookanista.bsky.social

instagram.com/wearebookanista

bookanista.com/author/farhana