A thousand and one tales of a philosophical life

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“A stunning biography of one of the most important thinkers of the last century.” Janice Gross Stein

What can Hannah Arendt possibly teach us today? What was, and still is one hopes, her indelible imprint on the world, on our humanity, on what she so unwaveringly upheld as civilisation? And who was she? How did she become that singular multitude of perspectives, human facets, existential and conceptual spaces that can certainly lay claim to have radically changed the way we see, and even act upon the world?

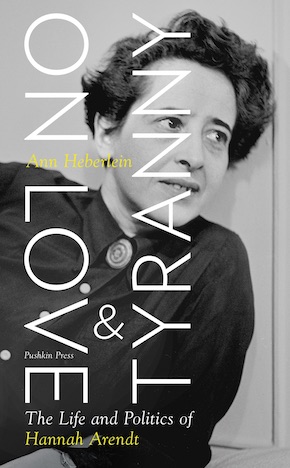

These questions, and especially the attempt to glimpse into the most intimate recesses of an extraordinary psyche, lie at the heart of Ann Heberlein’s ambitious biographical essay On Love and Tyranny: The Life and Politics of Hannah Arendt. With a strong resolve for authorial agency and control, Heberlein sets out to explore and interrogate a bios, but also to write what might at times seem like its definitive exegesis. She seeks to penetrate the depths of Arendt’s thought, to chart the periplous of her mind, but also to demolish any ivory towers of intellectualisation that may have encroached upon Arendt’s Nachleben. A key aim is to reposition Arendt firmly within the popular nous and imagination. Heberlein calls her throughout her ‘friend’ and ‘kinswoman’, and her account will be an explicitly intimate profile, rather than a detached scholarly study. Arendt becomes strictly Hannah, a rhetorical device intended to invite intimacy, to welcome familiarity, to break down barriers of difficulty or even of elitism, but also one which inevitably raises at least as many questions, as it undoes hurdles of affinity or accessibility. As a gemütlich or even widerborstig Hannah (the latter was Karl Jasper’s famous term of endearment for her), Arendt at times looms over Heberlein’s narrative as an eternally precocious, rebellious, even amorous adolescent, as a domesticated, even, Fräulein. The risk of a certain condescension and belittlement is inevitable, for all of Heberlein’s fervent engagement with, and almost confessional veneration for Arendt’s philosophical legacy, her human presence, her historical momentousness. As a result, On Love and Tyranny can be as beguiling as it can be ambiguous or at times problematic, and perhaps in equal measure.

Yet the decision to shift the focus from the exceptional to the everyday, from the colossal to the more classically human, is a formidable and a crucial one. It entails an understanding of the Aristotelian fallibility of heroes, the tragedy inherent in any human journey, the fallacies, woes, luminous vulnerabilities, and even the currents of hubris that permeate it. At the very heart of Arendt’s political philosophy is her unforgettable, controversial for many, epiphanic for others concept of the “banality of evil”, as well as the complex personal history of her own relationship with Martin Heidegger, a philosopher as undeniably seminal for the development of new structures of thought and analysis that persist with us even today, as he was tainted by both mundaneness and associations with that evil. As Heberlein puts it, Arendt’s thought and existence revolved constantly around “the major themes in her life: love and evil”. On Love and Tyranny will seek to examine these themes by capsulising the stages of an education (Arendt’s), and by delineating a philosophy of what should be humanity’s own paideia – even as it traces what has catastrophically been the latter’s process of deculturation, barbarisation, dehumanisation. As well as a vita of Arendt, Heberlein aspires in many ways to conceptualise a biography of humanity through her singular (yet not quite uniform) subject. Taking her cue from Arendt’s mother, who kept a meticulous diary of her daughter’s development and growth, On Love and Tyranny hopes to be a record of the remarkable ordinariness of an extraordinary life – a practical, irrefutable response to the perversion of what is normal, human and ordinary, that was Nazi Germany’s “banality of evil”.

Arendt’s radicalism is a revolutionary return to roots and first principles, to originary concepts of what thinking is all about and why it matters.”

The practical application of thought to everyday existence, to the subsistence of states and individuals, to the vita beata of both the secular moment and of eternity, was a constant concern for Arendt. According to Heberlein, she “wanted to change the world, but no longer believed in the power of philosophy to do so… Thus Hannah ended her relationship with the realm of theory, and decided to work practically and politically instead.” Arendt would call this “radical thinking”, and in fact, rather than the rejection Heberlein perceives, this emphasis on practicality, on praxis as opposed to abstraction, was in effect a radical redefinition and rehabilitation of philosophy, thought and theory itself. Arendt’s radicalism is a revolutionary return to roots and first principles, to originary concepts of what thinking is all about and why it matters. It is a gesture of survival, as she would write to Kurt Blumenfeld in 1947: “I have a kind of melancholy, which I can only grapple with by understanding, by thinking these things through.” It is as crucially a Socratic affirmation that the life of the mind is integrally vital to life in the streets and in staterooms. As such, it is a drastic, audacious defiance against what many have identified as the glib sophistry of Heideggerian abstraction, or the comparably problematic, for Arendt, formalism of Kant and his followers. It is Arendt’s answer, both intellectual and feminine, to the séduction du mal, whether as the lure of a ratiocinating supremacism, or the plainer (and more banal) male-female archetypes of domination and subjection that would have been prominent during Arendt’s formative years, and perhaps for most of her adult social and professional life.

As a hermeneutical reading of Arendt’s life and work, i.e. a biographical interpretation – or at least contextualisation – of her thought and its development and scope, On Love and Tyranny can offer interesting, unorthodox insight into Arendt’s intellectual growth, especially as a non-linear process of maturation and individuation. A series of somewhat meandering epiphanies, and an array of perhaps less luminous, mostly psychoanalysing realisations intertwine to underline the centrality for Arendt of a rigorously trained, passionately engaged and anxiously responsive mind. Heberlein points out the key role played by continental (and not just German) philosophy, as well as what Jaspers would call its Grenzsituation with Judaic thought, and especially by the radical reassessment of political theory and philosophy and its dire opposition to ideologies, together with Arendt’s determined, growing awareness of the essence and essentiality of Jewish identity. The nodal points of Heberlein’s discussion are Arendt’s relationships, and what she considers as Arendt’s key writings on political philosophy, namely The Origins of Totalitarianism, On Violence, Men in Dark Times and Eichmann in Jerusalem, which she engages in a critical dialogue with Arendt’s doctoral thesis on Augustine, and her biography of Rahel Varnhagen. At the core of Heberlein’s analysis lie the questions of goodness vs. reason, ethics vs. the individual mind, the life of duty vs. the life of what one has established critically as right; namely the difference between blind obedience, banal social integration and a true deontological ethics. The overarching concern is the actual living of a life, the fragility of that formidable mind, the vagaries of the heart that the nous sought to fathom, perhaps reign over.

At its best, On Love and Tyranny can boast a powerful immediacy of style, a panoply of deceptively simple verbal structures and conceptual strategies used to expose the stark realities we so often choose to ignore under the guise of a collective, of an a priori or an ideology, of a genealogy and an inherited story, especially of a claim to belong to a group or to a historical narrative with a particular or exclusive right to rectification or vindication. Although relying heavily on more or less systematising social theorists such as Pierre Bourdieu, Jonathan Glover, Philip Zimbardo, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Vladimir Jankélévitch, Seyla Benhabib or Judith Nisse Shklar, Heberlein also evokes more reflective voices, such as Martin Buber, Simon Wiesenthal, Emmanuel Levinas, Bruno Bettelheim or Walter Benjamin, as she seeks to articulate the essence of Arendt’s own analysis of what it means to think and to act, to be in the world, and especially her diagnosis of the social symptom of the “banality of evil”, in such a way that can silence the decades of indignant Arendt sceptics and critics. On the latter, she succeeds in clarifying Arendt’s crucial distinction between allocating culpability and demonising the perpetrator of a heinous crime. For Arendt, to demonise is to defamiliarise, to ‘other’, and thus to expiate the guilty (by creating a separate, exceptional moral category of judgement), but also the silent observer, the tacit collaborator, and therefore the passive participant, namely both Germany and the world at large. Concentrated efforts were made to identify a so-called ‘Nazi personality’ by Adorno, Horkheimer, Norbert Elias or Erich Fromm. Arendt reverses their question by asking how, under what conditions, through what banal mental and social processes does an ordinary man or woman shift to such a personality.

At its best, On Love and Tyranny can boast a powerful immediacy of style, a panoply of deceptively simple verbal structures and conceptual strategies used to expose the stark realities we so often choose to ignore.”

Arendt would make a point of claiming as her own the word ‘banality’ throughout her work – it is there, unwavering, in one of her most crucial writings, The Human Condition, where it is used to warn against the existential and moral pitfalls of what she saw as the rising eugenics of scientific progress, from biology to space exploration, to physics and artificial intelligence technology. She urges against the banal supremacism of “this future man [who] seems to be possessed by a rebellion against human experience as it has been given, a free gift from nowhere (secularly speaking), which he wishes to exchange, as it were, for something he has made himself.” The inherent totalitarianism of this is explicit: “There is no reason to doubt our abilities to accomplish such an exchange, just as there is no reason to doubt our present ability to destroy all organic life on earth.” The banality is inherent in the structural pervasiveness of the belief that techne is something opposed to nous, in the polarisation between “professional scientists or professional politicians” and political thinkers. It is a subtle distinction, but a vocal one: Arendt, for all her radical liberalism, or rather because of it, is ultimately a staunch believer in Plato’s philosopher kings.

Banalisation also involves language, the ability to communicate, articulate, create a thinking world and the words that can sustain being. From Nazi mind-perverting propaganda, to Orwellian Newspeak, or Heidegger’s appropriation of Greek in order to alienate it and with it thought itself, Arendt denounces too the banal process of depriving words, speech and writing of their vital function, true simplicity and meaningfulness. For her, science and, equally, social, philosophical and political ideological constructs have surpassed our ability to give them a coherent narrative: “the moment these ‘truths’ are spoken of conceptually and coherently, the resulting statement will be ‘not perhaps as meaningless as a “triangular circle”, but much more so than a “winged lion”’ (Erwin Schrödinger)”. Banal for Arendt is not what is plain or simple, but what becomes accepted as inevitably and unquestioningly routine, trivially commonplace. “Men… can experience meaningfulness only because they can talk and make sense to each other and to themselves.” Any future for humanity must include an education of the mind, the knowledge “of those other higher, and more meaningful activities for the sake of which this freedom [from labour, injustice or even the darkness of history] would deserve to be won… [It would require the ability] to think what we are doing” and why. For Arendt, and with perfect Socratic spirit, it is this absence of the ability or the freedom to think what we are doing and why that constitutes banality and, in so many instances, evil itself.

Throughout On Love and Tyranny, and perhaps throughout Arendt’s own writings and life, the feature that emerges with the most striking clarity is her persistence in translating everything – from the personal to the interpersonal, from the metaphysical to the ontological – into political or societal constructs. In fact, the metaphysical as well as the ontological are concepts that Arendt finds at times highly conflictual, even threatening. The personal and the interpersonal, on the other hand, are states she almost invariably treats with the ardour of total sublimation and abstraction. These are tensions that in another might have engendered a proclivity for master narratives and schematisation, for an intellectual despotism, even. In Arendt they would give birth instead to a thousand and one stories about thoughts and life, what she called Scheherazaderies, the tales that sought to make life not only bearable or understandable, but vitally and critically possible and shareable.

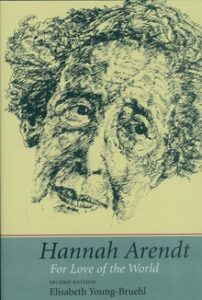

These tensions, multitudinous complexities and contradictions, Arendt’s own undeniably labyrinthine journeys, whether biographical, intellectual or philosophical, are at the heart of Heberlein’s book. They constitute its strongest asset, as well as perhaps its stumbling block. In her determination to write a humanising, but also explicative apologia of Arendt as a thinker and as a person, what is revealed is that with Arendt it is not so much a question of precise understanding, of defining the premises of categorisation, or of an evolutionary intellectual formation, as it is, rather, a case of an encounter, on Martin Buber’s terms of an I & Thou. On Love and Tyranny has a lot to commend it, not least the directness of its engagement with both its subject and its readers, and the concentrated effort to create a polyphony of perspectives, temporalities, frames of relevance. Yet it also treads a treacherous path between self-projection and critical analysis. Although free of the blatant misconceptions of Elzbieta Ettinger’s Hannah Arendt/Martin Heidegger, it is still heavily burdened at times by a propensity towards oversimplification and rather rustic psychoanalytic tropes. A clearer sense of focus, perhaps even of critical space between author and subject, would have allowed for a better balance between Heberlein’s personal voice and Arendt herself, a balance readers can find in Elisabeth Young-Bruehl’s more scholarly, vastly absorbing, Hannah Arendt: For Love of the World.

These tensions, multitudinous complexities and contradictions, Arendt’s own undeniably labyrinthine journeys, whether biographical, intellectual or philosophical, are at the heart of Heberlein’s book. They constitute its strongest asset, as well as perhaps its stumbling block. In her determination to write a humanising, but also explicative apologia of Arendt as a thinker and as a person, what is revealed is that with Arendt it is not so much a question of precise understanding, of defining the premises of categorisation, or of an evolutionary intellectual formation, as it is, rather, a case of an encounter, on Martin Buber’s terms of an I & Thou. On Love and Tyranny has a lot to commend it, not least the directness of its engagement with both its subject and its readers, and the concentrated effort to create a polyphony of perspectives, temporalities, frames of relevance. Yet it also treads a treacherous path between self-projection and critical analysis. Although free of the blatant misconceptions of Elzbieta Ettinger’s Hannah Arendt/Martin Heidegger, it is still heavily burdened at times by a propensity towards oversimplification and rather rustic psychoanalytic tropes. A clearer sense of focus, perhaps even of critical space between author and subject, would have allowed for a better balance between Heberlein’s personal voice and Arendt herself, a balance readers can find in Elisabeth Young-Bruehl’s more scholarly, vastly absorbing, Hannah Arendt: For Love of the World.

Arendt would have been highly sceptical of the current culture wars waged against the very tradition and values that allowed her to formulate a process of critical analysis, to reflect on what to do and how to be.”

Arendt’s political and philosophical quest, her spiritual and intellectual agon, were to define true humanity, Menschlichkeit; her aim was to provide the questioning and the journey, the critical apparatus of ethical reflection that would perhaps lead us to an ultimate ecce homo. There is an unquestionable heroic quality in such an undertaking, as well as an accompanying Aristotelian tragic fate, both of which are tantalisingly suggested, yet also muted, in Heberlein’s prosopography of Arendt. Equally hinted at, yet left undeveloped, is Arendt’s mistrust of movements, struggles, revolutions. In a letter to Arendt, Jaspers would write in 1951 that “Marx’s passion seems to me impure at its root, itself unjust from the outset, drawing its life from the negative without an image of man, the hate incarnate of a pseudo-prophet in the style of Ezekiel.” Arendt would agree, adding that Marx is “not interested either in freedom or in justice.” She would have been highly sceptical of the current culture wars waged against the very tradition and values that allowed her to think, to formulate a process of critical analysis, to identify right and wrong, goodness and evil, to reflect on what to do and how to be. She would have been deeply concerned by the compulsion for radicalised unrest, rather than radical action, by the disruption, rather than the redressing, of social structures, which seems to tacitly ignore, if not outright stand against societal building. She would have certainly detected more alarming origins of totalitarianism gaining both banality and ground.

Any attempt to defamiliarise her by polemical rejection, or to domesticate her by hagiographical adoration misses the point of Arendt’s exceptional, radical ordinariness: she was a fearless, indomitable, “devastatingly intelligent person”, to use Stanley Hoffmann’s words on Judith Nisse Shklar, someone trying to make sense of the world and its terrifying challenges. Her path is an odyssey to share, rather than blindly observe or react to, and perhaps it is what Jaspers called “her uncompromising desire for truth”, her unflinching willingness to engage with both the theory of life and its despair, the sheer force of her intellect, and the talent for friendships and relationships, for dialectics, for conversations of the mind and in real time, that lie at the heart of her universal resonance, as well as her uniqueness. In her preface to Men in Dark Times Arendt claims that it is “primarily concerned with persons – how they lived their lives, how they moved in the world, and how they were affected by historical time”, picking out Denys Finch Hatton’s motto “Je responderay”, I shall answer, and give account. It is quite possibly the best synopsis and emblem of who she herself was, of how she strove to be. As a short introduction to Arendt, On Love and Tyranny cannot go wrong; but for readers who want to engage more closely, more insightfully with Arendt and her work, Elisabeth Young-Bruehl’s critical biography is still the place to go. For those who wish to hear echoes of Arendt’s voice, and perhaps feel something of her presence, her own work, and even more so, from a personal perspective, the several volumes of her published correspondence with Karl Jaspers, Mary McCarthy, Kurt Blumenfeld, Gershom Scholem, her husband Heinrich Blücher, and even Martin Heidegger, offer privileged access to extraordinary worlds of friendship, humanity, reflection, history, as well as impressive moments of aporia and bafflement. They offer testimony to an indomitable mind, an exceptional life, a truly beguiling, ordinary human being who existed, in so many ways, both in and against time.

Ann Heberlein is the bestselling author of more than a dozen books, including A Little Book on Evil, A Good Life, and the autobiographical account of her bipolar disorder, I Don’t Want to Die, I Just Don’t Want to Live. In 2018, she debuted as a fiction writer with the novel Everything Is Going to Be All Right. She has researched and taught at the Department of Practical Philosophy at Stockholm University and at the Faculty of Theology, Lund University. On Love and Tyranny, translated by Alice Menzies, is published by Pushkin Press.

Ann Heberlein is the bestselling author of more than a dozen books, including A Little Book on Evil, A Good Life, and the autobiographical account of her bipolar disorder, I Don’t Want to Die, I Just Don’t Want to Live. In 2018, she debuted as a fiction writer with the novel Everything Is Going to Be All Right. She has researched and taught at the Department of Practical Philosophy at Stockholm University and at the Faculty of Theology, Lund University. On Love and Tyranny, translated by Alice Menzies, is published by Pushkin Press.

Read more

@PushkinPress

Alice Menzies holds a master of arts in Translation Theory and Practice from University College London, specialising in the Scandinavian languages. She has translated books by Fredrik Bachman and Katarina Bivald, among others. She lives in London.

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.

bookanista.com/author/mika/