Pioneers Awake!

by Alain Mabanckou

“A novelist of exuberant originality.” Guardian

The Director had been pulling strings to get his nephews Mfoumbou Ngoulmoumako, Bissoulou Ngoulmoumako and Dongo-Dongo Ngoulmoumako onto an ideological training course in Pointe-Noire so they could later become section leaders of the National Movement of Pioneers for our orphanage. They still remained under the control of their paternal uncle and particularly under that of two members of the USYC (Union of Socialist Youth of Congo), which was seen as the ‘nursery’ of the Congolese Workers’ Party because it was within this organisation that the government identified the young people who would go on one day to occupy positions of political responsibility in our country. The Director’s three nephews were thus promoted to a glorious future, which annoyed his three other nephews, on his mother’s side, Mpassi, Moutété and Mvoumbi, who were still stuck in their jobs as corridor wardens, though they too dreamed of becoming the orphanage’s section leaders of the National Movement of Pioneers. Unable to express their discontent to their uncle, they took it out on us instead. Their uncle had clearly favoured the paternal line over a family mix which might have calmed things down. Mpassi, Moutété and Mvoumbi felt they’d become underlings to the Director’s other nephews and we revelled in the stormy atmosphere among the wardens, which sometimes looked like spilling over into violence, until the Director intervened and threatened to replace them with northerners – which was enough to bring them to their senses…

It does not fall to everyone to become a section leader of the Union of Socialist Youth of Congo. The government sifted through the applications carefully, taking account of the ethnic origin of the candidates. As the northerners were in power – in particular the Mbochis – the leaders of the USYC were also Mbochis, an ethnic group which represented a scant 3.5 per cent of the national population. In other words, Dieudonné Ngoulmoumako had had to fight to fix the appointment of his three nephews, who were not Mbochi from the north, but Bembé from the south. In fact he had only partly got what he wanted because although they accepted his request, the political leaders of the Kouilou region suggested he go halves: his nephews could be section leaders, but under the command of the two northerners, Oyo Ngoki and Mokélé Mbembé, who in turn would be accountable to the national division at the annual congress in Brazzaville, to be attended by the President of the Republic himself.

“Those two old northerners who come every week for consciousness-raising sessions, how come they’re members of the Union of Youth, when they’re not youthful and their hair is whiter than manioc flour?”

Bonaventure was always pushing me to the limit. It was true that Oyo Ngoki and Mokélé Mbembé were the kind of adult who looked as though they’d never been young, with their dark suits, and myopic glasses. Either they spoke to us as though we were two- or three-year-olds, or they used their own special language which one of them had picked up in Moscow, the other in Romania. Mfoumbou Ngoulmoumako, Bissoulou Ngoulmoumako and Dongo-Dongo Ngoulmoumako copied their way of speaking, using the same expressions, which they didn’t understand and in which every sentence contained the word ‘dialectic’, or, as an adverb, ‘dialectically’:

“You need to consider the problem dialectically,” Bissoulou Ngoulmoumako would say.

“Dialectically speaking, our history has been written by the imperialists and their local lackeys, we must overthrow the system, the superstructure must not be allowed to outweigh the infrastructure,” Dongo-Dongo would affirm.

We never forgot, though, that before the Revolution the three former corridor wardens were just bruisers with zero intelligence. Now the Director had given them an office close to his on the first floor. They shut themselves in there to prepare Pioneers Awake!, a propaganda sheet that they posted on the wall of the hut of the National Movement of Pioneers every Monday morning. We had to read this publication before going in to class.

Our future President was busy terrorising the entire population of crocodiles who no longer dared even leave the water and come up onto the bank to breathe on account of the presence of this exceptional boy.”

In fact all Mfoumbou Ngoulmoumako, Bissoulou Ngoulmoumako and Dongo-Dongo Ngoulmoumako did was reproduce extracts from speeches by the President of the Republic that were reported back to them by the northerners, Oyo Ngoki and Mokélé Mbembé. Each issue also contained a passionate editorial by the Director, addressed to the President of the Republic. Dieudonné Ngoulmoumako worked hard on it, believing that the Head of State would read it on a Monday morning before summoning his government to lavish praise on him. He’d announce in his weekly column that the President of the Republic was invincible and had been sent to us by our Bantu ancestors. The saga of his life was one of the most extraordinary ever told on the black continent: as a teenager he had captured a crocodile by the tail on the bank of the River Kouyou, struck it with his bare hand, stunned it and brought it home alive to his grandmother, Maman Bowoulé, so she could cook it and feed it to the entire village. While our future President was busy terrorising the entire population of crocodiles who no longer dared even leave the water and come up onto the bank to breathe on account of the presence of this exceptional boy, his playmates were struggling to catch palm rats in their parents’ fields, or kill sparrows with catapults that couldn’t have broken so much as a tsetse fly’s foot. From which it can be seen that from a tender age our President was possessed of a sense of community spirit and a sense of sacrifice. He parleyed with mountain gorillas, protected elephants from poachers and spoke the language of the Pygmies, even though he had never actually learned it.

His second act of bravura was said to have taken place during the ethnic war between north and south, the former owing their victory to the intelligence of this precocious child, who advised the leader of his local combatants to dress up as an old lady and take him by the hand, as though he were her grandson. They crossed the line and arrived in the southerners’ camp, where, by eliminating their leader, Ngutu Ya Mpangala, and his lieutenant, Nkodia Nkoutata, they provoked a stampede, followed by the humiliating discovery, the next day, that they had actually been defeated by a toothless old lady and her grandson, and that neither of them possessed a single firearm. This exploit, and the adolescent’s intelligence in the art of war, so impressed the chief of Ombélé, the village where the prodigy lived, that he decided to send him to the military academy in Brazzaville. He was later posted to the Central African Republic, found himself in Cameroon with the rank of sergeant, and participated in the war being waged by the French against the Cameroons. When our country became independent, he was sent to Europe to complete his military training before returning to the fold with the rank of sub-lieutenant and all the aggression of a young wolf who wants to change everything as fast as possible. He had no time for the government he found in place, and therefore at the age of twenty-eight initiated the political upheaval which would carry him to power.

In his editorials, Dieudonné Ngoulmoumako underlined in bold that this was not a ‘coup d’état’, as was reported in certain books written by Europeans, who were known to be frontline enemies of our Revolution, because we’d claimed our independence and when they’d been slow about granting it, had shed our own blood for our liberty. The President’s mission was liberation, and he had fulfilled it with courage, and self-sacrifice. In creating the Congolese Workers’ Party, the Union of Socialist Youth of Congo, and the National Movement of Pioneers, he was simply obeying the word of our ancestors, whispered to him in his sleep. The days when he’d covered endless kilometres on foot with a piece of manioc and a bit of smoked crocodile meat for sustenance were behind him now. According to Dieudonné Ngoulmoumako, the President was on a par with Jesus Christ, carrying on his shoulders all the sins of the Congolese people since the dawn of time…

I remember it was the first issue of Pioneers Awake! that confirmed that the government had decided to ban religion in all public institutions, including orphanages, with immediate effect, as the enemies of the Revolution were extremely keen to put a stop to our march towards the future. This same government decreed that the teaching of Marxism–Leninism should be our country’s priority. When we struggled to understand how Papa Moupelo could possibly be an undesirable, since he had nothing to do with politics, the news sheet said that it was because he was one of the accomplices of the imperialists, that they often used priests to undermine our youthful scientific socialist Revolution. We don’t know which, but one of Mfoumbou Ngoulmoumako, Bissoulou Ngoulmoumako or Dongo-Dongo Ngoulmoumako had drawn a crude caricature of our priest, showing him dressed as a magician from hell, hypnotising his audience, with the caption written in bold: Religion is the opiate of the people.

It was clear that Mfoumbou Ngoulmoumako, Bissoulou Ngoulmoumako and Dongo-Dongo Ngoulmoumako were incapable of running a news sheet which was so eloquent and intelligent in its expression. Most of the articles were thought up and written by Oyo Ngoki and Mokélé Mbembé, those two ‘oldsters’, who were probably also the ghost writers for Dieudonné Ngoulmoumako.

***

As for the hundred or so girls in the orphanage, they were putmunder the control of Madame Maboké, who spoke on behalf of the First Lady, President of the Revolutionary Union of Women in the Congo (RUWC).

The name of the President’s wife was constantly on Mme Maboké’s lips, and she would assure the girls that the First Lady was aware of their situation. On odd occasions she would arrive with an army of old mamas who would teach our young friends the rudiments of cooking with minuscule utensils which were supposedly appropriate to the age of the girls. Other times it was young girls who turned up to share with them the secrets of braiding and manicures. At these times the orphanage would be on the alert, and, in our separate dormitories, we’d rush to the window to catch a look at the ‘gazelles from Pointe-Noire’, as we called them, dressed in tight trousers and pointed heels, with their pagne pulled tight about them and their backsides popping like grains of corn in boiling palm oil. They’d wander about the yard and wave to us from a distance, until those bruisers Mpassi, Mvoumbi and Moutété appeared, objecting to these women from Pointe-Noire showing a kindly interest in us, when they scarcely even looked at them.

We longed to be little mice, and hide secretly in the girls’ building and watch what the gazelles from Pointe-Noire taught them. In any case, our fellow inmates of the opposite gender were wreathed in smiles – perhaps to show us they were happier than we were – and we’d hear the echo of their laughter or applause, the cause of which wasn’t clear, but which we joined in with anyway, from our own buildings, just to show them that we envied their happiness, and that we too would have liked to be girls like them, in these moments of delight.

Two hours later, the gazelles of Pointe-Noire crossed back over the yard, looking round for us, to thank us for having applauded even though we’d seen nothing, but we didn’t dare brave the three corridor wardens, who were hiding out somewhere, not to watch us, but to get a sight of these lovely creatures’ backsides. We would hear, with some sadness, the sound of an engine of a less tubercular variety than that of Papa Moupelo’s vehicle: it was Madame Maboké’s car. Not for one single moment had she taken her eyes off these young members of the Revolutionary Union of Women in the Congo, whose mission was to do the rounds of the orphanages, seeing to the proper education of our girls…

Extracted from Black Moses, translated by Helen Stevenson

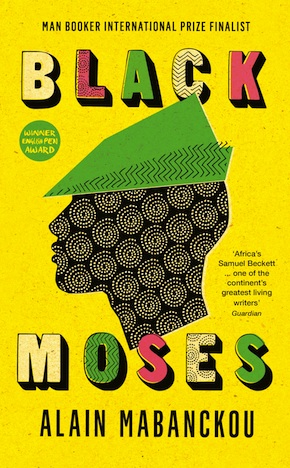

Alain Mabanckou was born in 1966 in the Congo. He currently lives in LA, where he teaches literature at UCLA. He is the author of six volumes of poetry and six novels. He is the winner of the Grand Prix de la Littérature 2012, and has received the Subsaharan African Literature Prize and the Prix Renaudot. His previous books include African Psycho – now reissued as a Serpent’s Tail Classic – Broken Glass and Memoirs of a Porcupine. Black Moses, out now in hardback and eBook from Serpent’s Tail, is longlisted for the 2017 Man Booker International Prize. Read more.

Alain Mabanckou was born in 1966 in the Congo. He currently lives in LA, where he teaches literature at UCLA. He is the author of six volumes of poetry and six novels. He is the winner of the Grand Prix de la Littérature 2012, and has received the Subsaharan African Literature Prize and the Prix Renaudot. His previous books include African Psycho – now reissued as a Serpent’s Tail Classic – Broken Glass and Memoirs of a Porcupine. Black Moses, out now in hardback and eBook from Serpent’s Tail, is longlisted for the 2017 Man Booker International Prize. Read more.

alainmabanckou.com

@amabanckou

Alain Mabanckou in Point-Noire, Congo © Caroline Blache

Helen Stevenson is Alain Mabanckou’s regular translator, as well as translating works by Marie Darrieussecq, Alice Ferney and Catherine Millet. She is the author of the novels, Pierrot Lunaire, Windfall and Mad Elaine, and the memoir Instructions for Visitors. She lives in London.