Polar bears in Auschwitz

by Mika Provata-Carlone

“An unforgettable, heartbreaking novel.” Publishers Weekly

“When I was in second grade, I found a piece of paper on my desk with the words, ‘You are a Jew’. I went home and asked: ‘Mum, what is a Jew?’ She explained that people have different religions, Christians, Protestants and Jews in Czechoslovakia. I said: ‘And we are Jews?’ The answer was a simple ‘yes’.” This is how Dita Kraus, the real person behind Antonio Iturbe’s Dita Keller, and the true ‘librarian’ of Auschwitz, recalls discovering her Jewish identity in a 2018 interview with the Jewish Chronicle.

This identity was to condemn her, together with millions of others, to the horrific fate of the Holocaust, the word fate being here a particularly cruel, sarcastic misnomer for what was perhaps the most atrocious conception of the individual and collective human mind. Dita Kraus’ story is the story of so very many – and it is also remarkably unique, almost beyond mere rational belief. Her family followed the path from comfortable middle-class life to initial racial exclusion, then ghetto segregation, and finally the via dolorosa of consecutive concentration camps. She was interned in Auschwitz-Birkenau, evacuated to Bergen-Belsen, which she miraculously survived, at least physically. She would spend the post-war years in Israel, teaching. Teaching how to remember, and how to build the future on the strength of the terrible wisdom of that remembrance.

The radically critical, vital role of education is at the heart of Kraus’ experiences in Auschwitz-Birkenau, in a way that seems utterly surreal, hallucinatory even. In the midst of their extermination camp, where inhuman labour beyond human endurance would literally set prisoners free from life (if they had survived the selection process, that ‘liberated’ others with the satanic expediency of the gas chambers), the Germans had set up a family camp that included a children’s block, complete with ‘classrooms’. There were meant to be no children in Auschwitz – they were selected by default for the gas chambers upon arrival. The family camp, and its 300 children, were intended to serve as a decoy for international inspectors, as a palliative to their conscience and as a sedative to their faculty of reason, their instinct of humanity.

The rooms allocated to serve as classrooms were decorated with murals depicting characters from Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, Eskimos, flowers, storybook characters, ‘normal’ children’s themes.”

In this idyll of horror, which had a regular life cycle of six months, prisoners were assigned as teachers under the formidable leadership of Fredy Hirsch, a German Jew who had made his mark before the war as an exceptional athlete. Hirsch had already organised children’s groups in Prague and in the Terezín ghetto, where insubordination for the children’s benefit would lead to his transfer to Auschwitz-Birkenau. The rooms allocated to serve as classrooms were decorated with murals painted by Dina Gottliebova Babbitt and Marianne Hermann, depicting characters from Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, Eskimos, flowers, storybook characters, ‘normal’ children’s themes. The children learnt geography and nursery rhymes, played games and staged a play, again Snow White and the Seven Dwarves, for an audience that included Josef Mengele. There were no pencils, but there were ‘living books’, namely prisoners who could recreate stories from memory.

Hard as it is to believe, since printed knowledge of any kind in the hands of prisoners was anathema to the Nazis, there were also real books, pilfered from the confiscated luggage of arriving deportees. Kraus herself, whose extraordinary role was to be the keeper of these books, remembers only A Short History of the World by H.G. Wells, in a Czech translation. Other survivors recall a geographical atlas and one of the works by Sigmund Freud, as well as a a book of short stories by Karel Čapek, brother of Josef, the inventor of the word ‘robot’ and an artist of extraordinary vision and power. Karel died in 1938, and Josef did not survive the Holocaust. As for Hirsch, Kraus learned much later that Jewish doctors, worried about his safety, had drugged him to avoid conflict, but misjudged the dose. Iturbe lists eight books as part of the ‘library of Auschwitz’: an Atlas, a Basic Treatise on Geometry, A Short History of the World, a Russian Grammar, a ‘French novel’, Freud’s New Paths to Psychoanalytic Therapy, a ‘Russian novel’ and the suggestively evoked The Adventures of the Good Soldier Švejk by Jaroslav Hašek.

“Throughout history, all dictators, tyrants and oppressors, whatever their ideology… have had one thing in common: the vicious persecution of the written word. Books are extremely dangerous: they make people think,” intones Iturbe early on in his story, and he uses books, the stories sustaining these spent, or in the eyes of the Nazis, expendable lives to trace how what used to be normal and what used to be beautiful are now monstrous and terrible. Music, a train journey following the points on a map, animals that capture a child’s imagination, landscapes that describe an ecosystem, a caress (Mengele would often pet the children he would then select), even humanity.

For Dita Keller, for Dita Kraus, for many of the unextinguished minds and consciousness of the otherwise dehumanised prisoners, certain books are life-threads. Cronin’s The Citadel is Dita Keller’s inner voice and guide, together with Mann’s Der Zauberberg, Wells’ Short History and especially the story of the not so very intelligent yet all too human Everyman that is Švejk. In a world of lethal silence they are the polyphony of voices, the human society and company, that is here under threat of imminent extinction. They also provide a template of coherence, or a comparative background for the monstrous incoherence that should still enshroud that moment and that act in human history.

The question behind every human figure, fictional or real, every gesture, episode, story is the same: how can the human mind be capable of the very conception of evil, let alone its execution and implementation? When does evil begin? Does it ever, can it ever stop? Have we listened to the story of the Holocaust? Heeded its horrors, felt deeply its traumas and significance? Or have we relegated it to the jurisdiction of History rather than to the more real responsibility of our souls?

The story that Iturbe puts together, interweaving the strands of many independent narratives, is utterly and relentlessly devastating, an agonising inventory of martyrdom and endurance, a cosmology of pain, suffering and evil, of a humanity striving to survive beyond all hope and against all odds. The first part dealing with Auschwitz is painstakingly documented, fierce and chilling in its minutiae that make up what was neither death nor life, the unspeakable world of the extermination camps at the peak of their operation. The second part, recording the abysmal collapse of the Third Reich and the frantic attempts to contain the crimes and the losses, gives us Bergen-Belsen, a place beyond even the horror of Auschwitz, a space beyond terror and destruction, beyond annihilation and nothingness. The British who would liberate the camp on 15 April 1945, “soon realised that they can’t be as respectful towards the dead as they would like; the spread of diseases is too rapid. In the end, they order the SS guards to pile up the bodies and a bulldozer pushes them as far as the pit. Peace is very demanding. It has to wipe out the effects of war as quickly as possible.”

Iturbe is a journalist and his skills as a researcher, as a shrewd news storyteller who can identify the headline and the angle for a narrative, are in full evidence here.”

The Librarian of Auschwitz seeks to be an epic that speaks for every soul lost, every life desecrated and sacrificed, every experience at the very edge of being. Iturbe is a journalist and his skills as a researcher, as a shrewd news storyteller who can identify the headline and the angle for a narrative, are in full evidence here. He makes an intense effort to recreate both worlds of peace and war, the smells, contexts, sounds, textures, images, sensations and feelings, the presences and absences. He also has the most poignant material in his hands, the unique testimony of a living, extraordinary, indomitable survivor, Dita Kraus.

It is both a tremendous opportunity and a challenging task. A woman’s life becomes another man’s imagination; a person’s voice, another person’s echo. The need to record, to tell, to bear witness on Iturbe’s part unfortunately is not always in perfect balance with the requirements of creating a narrative that, though part fiction, as Kraus says in her own preface, still rings true, has the authenticity, the flesh-and-blood quality of the real lives behind it. The Librarian of Auschwitz needed a storytelling voice that would speak the horror of the Holocaust without tainting it, as it sometimes does, with ‘literaturisms’.

Just as books can have a higher symbolic value, can transfigure places, lives, people, history itself and even the reality of our humanity, so can they manipulate it, objectify it, perniciously entrap it and falsify it. The Holocaust should not ever become a ‘literary genre’. It cannot be historical fiction. Tragedy – and the Holocaust stands for the ultimate human tragedy – does not need ‘drama’ or literary tropes, ‘action’ or embellished characterisations, intricate plots full of intrigue and emotional interest. The story of Fredy Hirsch (full of silences, erasures, questions and unresolved, tragic riddles), the story of Yakub and Miriam Edelstein and their children, of Anne Frank and her sister Margot, of people like Iturbe’s Professor Morgenstern, of Dita Kraus herself, need no more than all that they are, a pure language of pain, a very humble act of memory. The authorial praxis and presence in The Librarian of Auschwitz is not always a comfortable one. Unlike Ebury in the UK, which has launched the book through its adult list, Henry Holt in the US defines the target audience as being in the 13–18 age group (the Kirkus review narrows it down further to 13–16s). This may explain the emphatically exegetical tone, the more directed and structured narrative agenda. Whoever reads The Librarian of Auschwitz, however, will not fail to be struck at the very heart of their being and humanity by all that it reflects, all that it tries to contain.

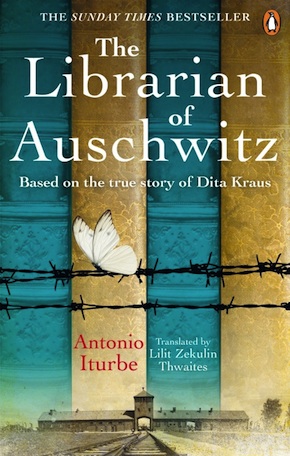

Antonio Iturbe lives in Spain, where he is a novelist, a journalist and director of the cultural magazine Librújula. The Librarian of Auschwitz, translated by Lilit Zekulin Thwaites, is published in paperback, eBook and audio download by Ebury Press.

Antonio Iturbe lives in Spain, where he is a novelist, a journalist and director of the cultural magazine Librújula. The Librarian of Auschwitz, translated by Lilit Zekulin Thwaites, is published in paperback, eBook and audio download by Ebury Press.

Read more

@EburyPublishing

@ToniIturbe

Lilit Zekulin Thwaites is an award-winning literary translator. After thirty years as an academic at La Trobe University in Australia, she retired from teaching and now focuses primarily on her ongoing translation and research projects.

Mika Provata-Carlone is an independent scholar, translator, editor and illustrator, and a contributing editor to Bookanista. She has a doctorate from Princeton University and lives and works in London.